Tens of thousands of Jews are choosing to become German citizens.

Unreal?

It’s happening.

A study at Tel Aviv’s Bar Ilan University study found 100,000 Israelis have German passports.

During the Nazi era, the 1935 Nuremberg racial laws stripped Jews of German citizenship. But since May 1949, German law gives Jews who fled Nazi Germany the right to German citizenship, including all their descendants.

“This is the largest group of German passport holders in the world outside Germany,” said Emmanuel Nachshon, Deputy Ambassador at the Israeli embassy in Berlin.

There are an estimated 15,000 Israelis in Berlin, drawn there to work, study and enjoy Berlin’s intellectual life and cheap rents. “It’s the single most interesting and dynamic city certainly in Europe and perhaps in the world,” said Nachshon.

Israelis comfortable in Germany

Maya Nathan agrees. The 33-year-old Israeli student with a German passport said “I fell in love with Berlin, its freedom, its great space.”

Nathan is not uncomfortable about living in the country responsible for the Holocaust. “Our family was never anti-German,” she said, adding that she knows Israelis who won’t come to Germany.

Nathan, who has been in Germany for two and a half years, is getting a neuropsychology degree at the University of Magdeburg. She plans to remain in Germany.

Nadav Gablinger, 39, is a tour guide who has lived in Berlin for 11 years. An Israeli with German citizenship, he and his Israeli wife have two children in German schools.

Noting that Holocaust history is everywhere in Berlin, Gablinger says that present-day Germany is a very safe place for Jews.

“Today I can say as a Jew, Germany is the safest place in the world,” he says, “Safer than in Israel.”

Nachshon speculated that many Israelis hold second passports in case things go wrong in Israel.

American granddaughter of Holocaust victims: ‘We made it back’

Increasing numbers of American Jews are also seeking German citizenship.

According to German government figures, 3,663 Americans, mostly Jews, acquired German citizenship between 2003 and 2010.

German citizenship allows American Jews not only to live and work in Europe, but also access to a free university education. So it could be that some seek German citizenship so they can live and work elsewhere in Europe.

“Berlin is becoming one of the most exciting capital cities in Europe, and it exerts a pull,” said Deidre Berger, director of the American Jewish Committee in Berlin. “Many of the new Jewish citizens say they have some history in Germany and they want to discover it.”

Suzanne Houchin, a 50-year-old photographer from Los Angeles, is one of them. She and 10 other family members received German passports two years ago.

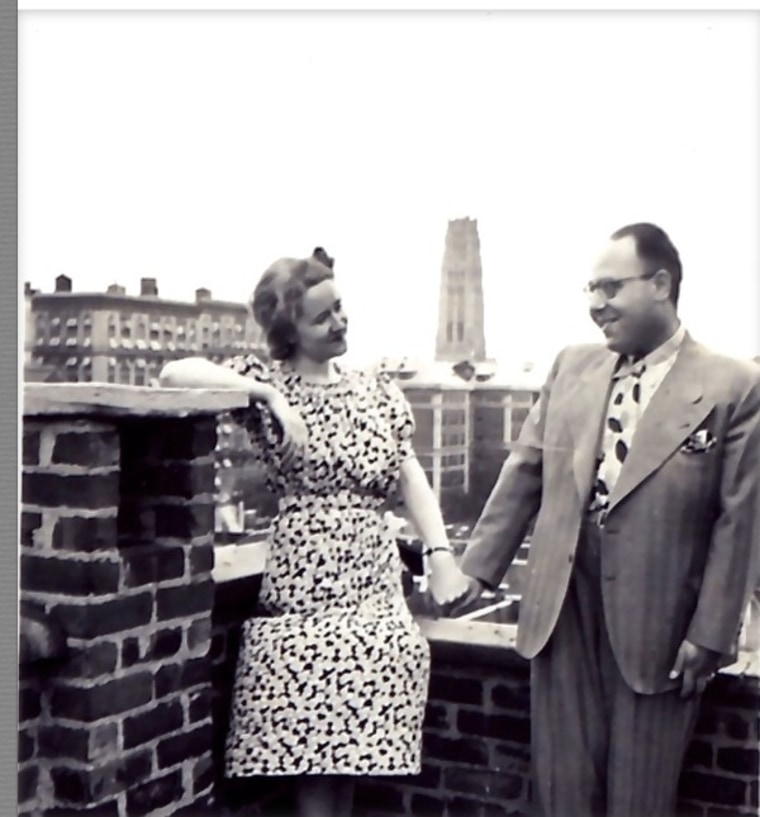

Houchin’s grandparents, Bruno and Hedwig Gumpert, who owned a department store in the city center, fled Berlin in 1939.

“My grandparents would talk about their wonderful childhood in Berlin and how much they loved Germany,” she said in a telephone interview. “They were our bedrock and they meant the world to us.”

Explaining her feelings about becoming a naturalized German, Houchin said: “It felt like this was a way of honoring them, getting back something that was stolen from them.” She tearfully added, “Mein opa (my grandfather), we made it back to the land that you loved so much. This makes my heart happy.”

Dr. Ruth: ‘Hitler did not want me to have children’… now they can become citizens

Dr. Ruth Westheimer, the 83-year-old renowned sex therapist, born in Frankfurt, is also proud of her German citizenship, acquired in September 2007.

When she was 10 years old, Westheimer’s parents put her on one of the last trains to a children’s sanctuary in Switzerland. After the war, she learned her family had been killed.

“Hitler did not want me to have children, or grandchildren,” she said in a telephone interview. “Now that I have a German passport, my grandchildren can study anywhere in Europe.”

But Edward Levy, 30, a naturalized German from Chicago, is wary. “Sometimes I wonder what the older generation [of Germans] really thinks,” he said. “If they knew I was Jewish and my grandparents were Jewish.”

Seattle-born Jordan Selig, 25, relishes her new life in the gritty Kreutzberg district of Berlin. A Columbia University graduate, she buys apartments to renovate as rentals. Her grandparents fled the Nazis on the trans-Siberian railroad to China. She said they boarded the last passenger ship to leave for the United States before war broke out.

“It’s so much more comfortable and international to live here than in most big cities,” she observed.

As time passes, gets easier

“Berlin is the place to be for young people,” said Nirit Bialer, a 33-year-old Israeli and granddaughter of Holocaust survivors. “There’s a lot of space here, and there is freedom and acceptance of artistic innovation. Individuality is strong here. In Israel, the collective is much stronger.”

Bialer runs Projekt Habait, a German-Israeli social program to inform Germans about Israeli culture. “Many of the Israelis here are engaged in the art scene and some are known here. However, there is a big hunger among Germans to learn about us.”

The Holocaust remains an open wound for many Jews. But Berger, from the American Jewish Committee in Berlin, believes the wound will heal.

“I think it’s getting easier for third and fourth generation Americans with German roots to look at Germany in a more open-minded way as the distance from the Holocaust grows.”