Researchers say marks on Richard III's bones confirm the centuries-old saga of the English king's death — including claims that the killing blows were delivered to his skull, and that vengeful foes stabbed his corpse after death.

"The contemporary accounts of the battle tally with what we've seen on the skeleton," said the University of Leicester's Sarah Hainsworth, one of the authors of a study published Tuesday by The Lancet, a British-based medical journal. "It's a great testament to modern forensic science and engineering that we can go back more than 500 years in history and learn how a person of that age died."

Centuries-old mystery

For many of those years, Richard III's fate was a mystery, with one of literature's best-known villains at its center. William Shakespeare made him out to be a cold-hearted schemer in "Richard III" — many would say unfairly so. But the bard also gave him some of the canon's best-known catchphrases, ranging from "the winter of our discontent" to "A horse, a horse! My kingdom for a horse!"

Richard's death at the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485 marked the end of England's decades-long War of the Roses. The stories say that his body was thrown on top of a horse, exposed to scorn, and eventually buried at Leicester's Greyfriars Church. But for centuries, historians didn't know exactly where his bones were laid.

An archaeological excavation found a promising set of bones beneath a Leicester parking lot in 2012, and DNA testing confirmed that the bones were Richard's. Since then, researchers have been trying to glean as much as they could from the remains before next year's ceremonial reinterment in Leicester Cathedral.

The researchers have already done a reconstruction of Richard's face and determined what he suffered in life — including a case of scoliosis that affected his posture, but didn't make him out to be the gruesome hunchback Shakespeare described.

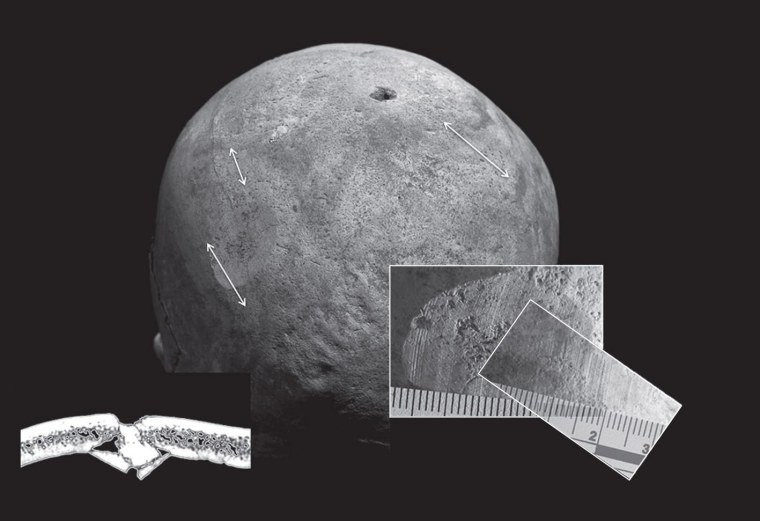

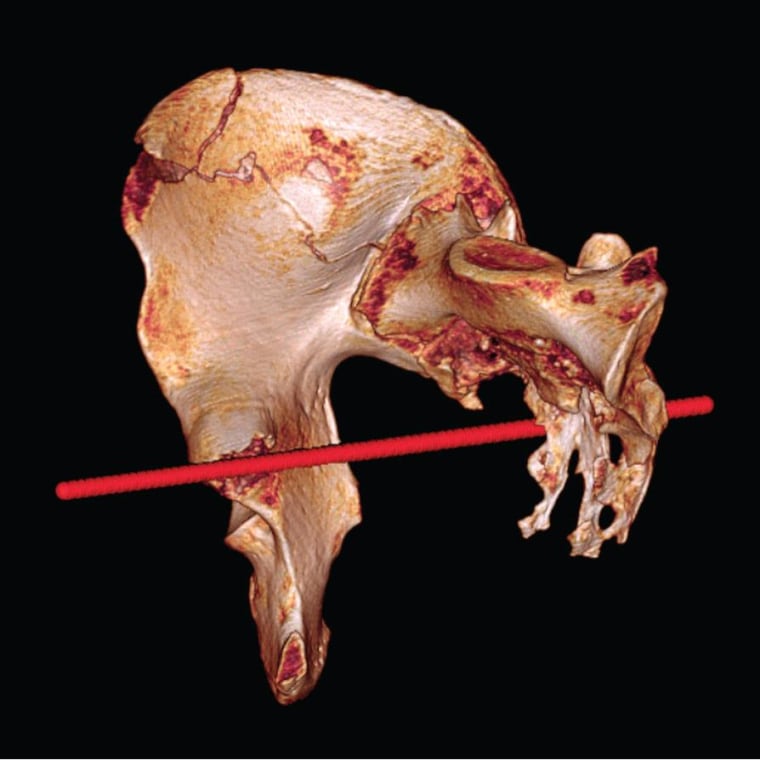

The study published in The Lancet focused on what Richard suffered in death, based on analysis of whole-body CT scans as well as micro-CT scans of injured bones.

Wounds upon wounds

The University of Leicester team, led by archaeologist Jo Appleby, counted nine wounds to the skull. That suggested that the king had removed or lost his helmet on the field of battle. University of Leicester pathologist Guy Rutty said two of the skull injuries were the most likely to have caused his death. One was a heavy blow to the bottom of the skull, possibly coming from a sword or staff weapon. The other was a penetrating injury from the tip of an edged weapon.

"Richard's head injuries are consistent with some near-contemporary accounts of the battle, which suggest that Richard abandoned his horse after it became stuck in a mire, and was killed while fighting his enemies," Rutty said in a news release.

Hainsworth said the fact that there were no wounds to the bones of the arms or hands indicates he was still wearing armor when he died.

The bones show additional wounds to the pelvis and a rib bone. The researchers argue that 15th-century armor would have guarded against those kinds of injuries — and that led them to conclude the jabs were inflicted after death. Such a view meshes with contemporary accounts claiming that Richard's foes delivered "many other insults" to his corpse when it was taken from the field.

Questions remain

Hainsworth acknowledged that she and her colleagues could only study injuries to the bones, and couldn't draw any conclusions about soft-tissue injuries. "If he'd been stabbed right through the rib cage and into the heart, he would have died just like that," she told NBC News.

Because of that limitation, the interpretation of skeletal injuries "should always be approached with caution, particularly when the remains are those of a prominent historical figure," Heather Bonney, an expert on human remains at London's Natural History Museum who was not directly involved in the study, said in an emailed statement.

Bonney also pointed out that the University of Leicester team's DNA findings about the remains have not yet been published in a scientific journal. "It appears somewhat unorthodox to publish the analysis of the remains before unequivocally identifying them," she wrote.

Nevertheless, Bonney said the team provides "a compelling account, giving tantalizing glimpses into the validity of the historic accounts of Richard III's death, which were heavily edited by the Tudors in the following 200 years."

Hainsworth said the study left her wanting still more. "You almost wish you could go back in time and observe what he was like," she said.

Between now and next March's reinterment, researchers will be reviewing their data to make sure they've "completely answered all the questions we want to answer, because we won't get another opportunity," Hainsworth said.

But there may be other cold cases to solve — for example, the mystery surrounding the fate of King Alfred the Great's remains. "I greatly hope we'll be able to work with archaeologists again where our skills and expertise are valued," Hainsworth said.