Scientists have discovered a new material that can capture and concentrate methane, a potent greenhouse gas.

While carbon dioxide, the most abundant greenhouse gas, can be captured using a variety of techniques, methane capture has proved elusive primarily because it interacts weakly with other materials, according Amitesh Maiti, a researcher at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

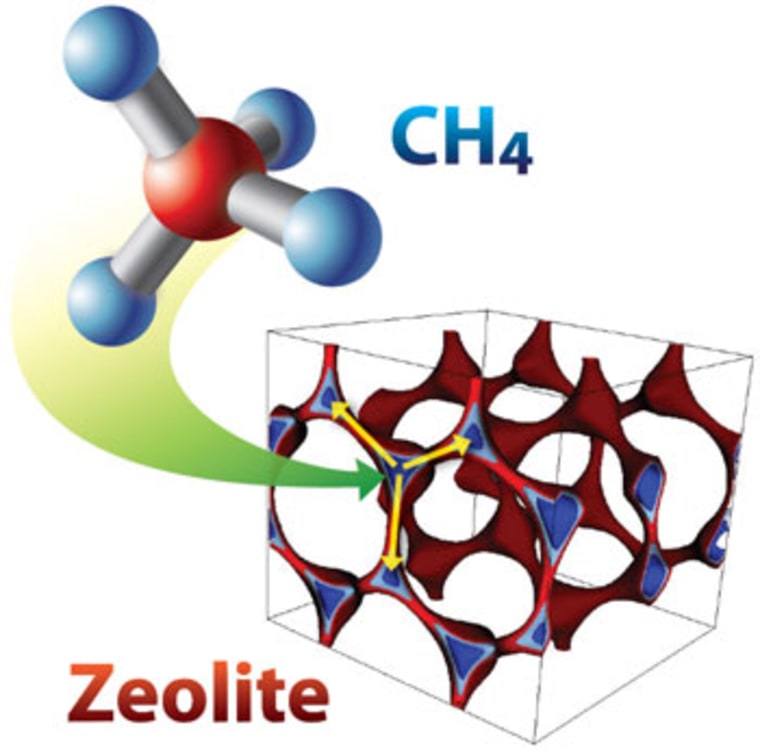

He and colleagues discovered that various forms of zeolites, which are commonly used in water purification and other industrial processes, appear well-suited for the task. That's because the material's crystalline structure can be fine-tuned for various gas separation or storage applications, he explained.

Using computer simulations, Maiti and colleagues searched through a database of about 100,000 different forms of the material and found several that appear technologically promising for capturing methane.

A couple of the forms actually exist — they have been made — "and then there are theoretical zeolites which in theory can be made, but have not been made yet," Maiti told NBC News.

Going forward, he hopes other researchers will be inspired by the new work published Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications and begin to experiment with zeolites in the real world.

The simulations indicate, for example, that the material could capture low concentrations of methane venting from coal mines or piles of manure at feed lots and concentrate it up to just over 5 percent, which is the flammability limit of the gas.

"You can utilize (the methane) to generate electricity," Maiti said, explaining one of the many applications for the recovered gas.

While in an early stage, the technology is potentially promising given that concern about methane emissions at hydraulic fracturing sites is on the rise and the potential for large-scale releases of methane as the Arctic permafrost thaws.

While zeolites are unlikely to be of much use soaking up methane released in the Arctic, anything that can be enveloped — from feedlots to coal mines and potentially even well pads — the material might be an economically viable solution to methane recovery, Maiti said.

John Roach is a contributing writer for NBC News. To learn more about him, visit his website.