Mike is a teaching assistant in New York City, and to supplement his income, he has a second job: He sells drugs. But Mike, who spoke on the condition that his last name not be published because he was discussing illegal behavior, isn’t your stereotypical street-corner dealer. When it comes to pushing his product, he said there’s an app for that: Grindr.

“It gives me more clientele than I would normally get on the street,” Mike said of the popular gay dating app. He added that selling on Grindr is safer since he doesn’t have to worry about confrontations with other dealers “about who sells in what area.”

The rise of gay dating sites in the 1990s, such as early entrants Manhunt and Adam4Adam, provided gay men with new ways to connect. But over time, digital platforms geared toward LGBTQ men have also created a more convenient way for gay and bi men — a population that disproportionately uses illicit substances due to social stigma, discrimination and other minority stressors — to find drugs, and for drug dealers to find them.

“Today with Grindr, men can have sex and drugs delivered to their door instantly,” Phil McCabe, a social worker and president of the National Association of LGBT Addiction Professionals, told NBC News.

Grindr, by far the world’s most popular gay dating app with an estimated 3 million daily users, has previously taken steps to address the buying, selling and promoting of drugs on its platform. However, those who use the app say it is still home to a robust market for illicit substances.

“The issue with drugs has been a gay community plague since the ‘80s, but in the modern era, you don’t need a guy who knows a guy,” Derrick Anderson, a Grindr user from Chicago, said. “All you need to do is open up your app and look for that capital ‘T.’”

SECRET LANGUAGE

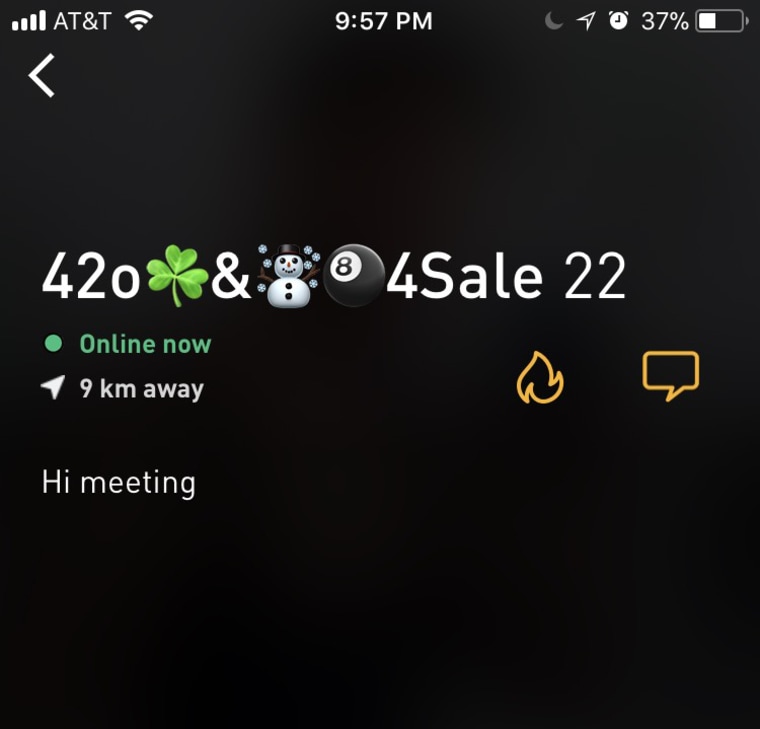

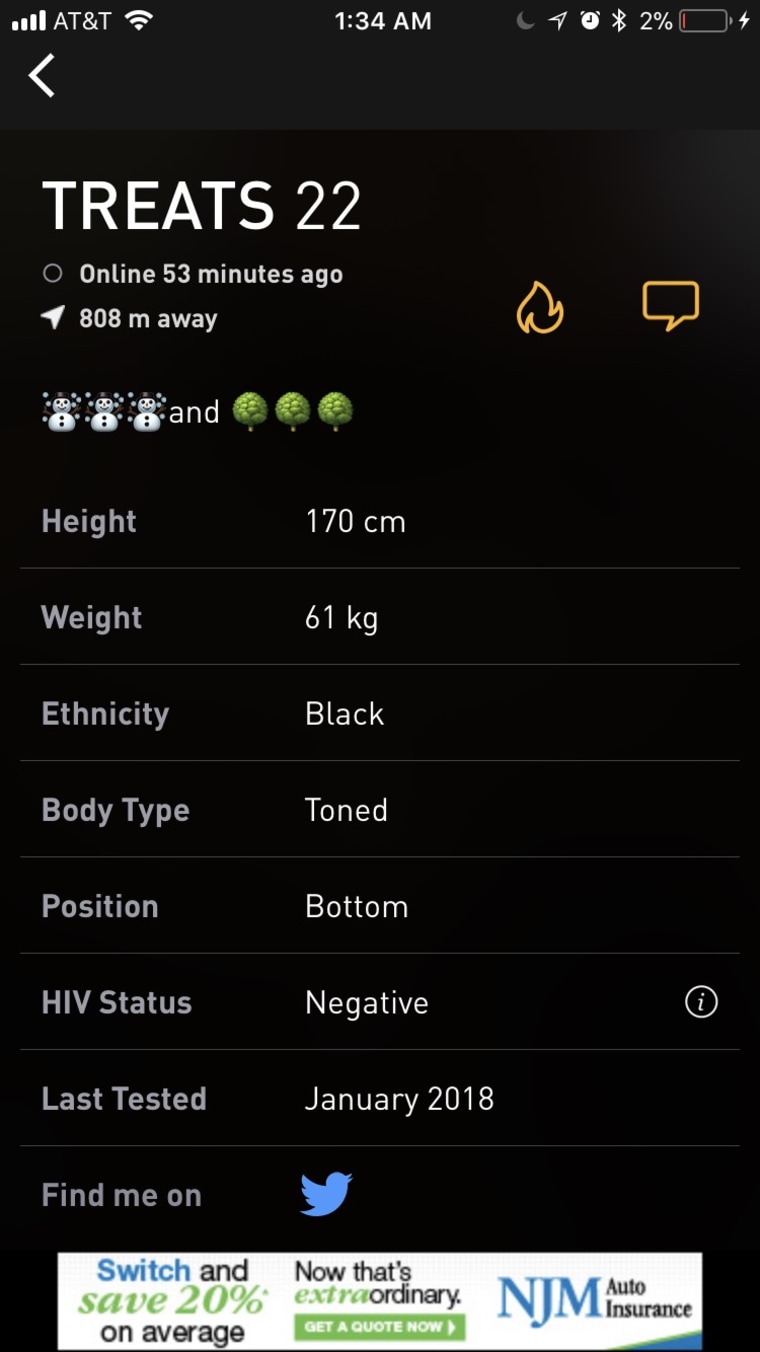

Those who are new to Grindr may be confused by all the seemingly random capital letter Ts and acronyms in Grindr profiles — that’s because some drug buyers, sellers and users on the app have their own language.

The terms “parTy and play” and the acronym “PNP,” which can be seen on Grindr and beyond, are used by some gay men to describe a sexual encounter while under the influence of drugs. The capital T refers to meth’s street name, “Tina.”

Some people on the app are explicit about their intentions with drugs, while others have covert ways to indicate whether they’re looking to buy, sell or just “parTy.”

Travis Scott, 22, a Grindr user in Toronto, said he gets a message “nearly every day from someone asking if I’m into ‘PNP.’”

“I didn’t even know what it stood for until I asked my roommate about it,” he said.

Beyond code words, there’s also a plethora of symbols and emojis that are used to indicate drugs. Grindr users discreetly reference crystal meth by putting a diamond emoji in their profile, and snowflake emojis are used to get the attention of those looking to purchase cocaine.

A ROBUST MARKET

While there is no data that quantifies drug activity on Grindr, a dozen people who use the app spoke to NBC News about its prevalence.

“I think it’s gotten worse in the past couple of years,” said McCabe, who in addition to being a social worker also uses the app. He recalled being messaged on Grindr by someone who was offering “parTy favors.”

“Now I know he wasn’t bringing red Solo cups. He was selling drugs,” McCabe added. “The apps are making it easier for people to find him.”

Ethan, 23, a Grindr user in Michigan who spoke on the condition that his last name not be used because he did not want to be associated with drug use, said there is nothing in his profile that implies he is interested in buying or using drugs, but nonetheless others “still message looking to sell.”

“It is definitively more prevalent than it used to be,” Ethan, who has been using the app on and off for two years, explained. “I’ve been offered meth and crack cocaine, which is absolutely insane to me.”

George, 30, a Grindr user in New York who asked that his last name not be published out of concern for his safety because there are drug dealers in his neighborhood, said over the past two years the increase in Grindr profiles that mention buying, selling or using drugs “has been exponential.”

“Drugs were always sprinkled throughout the app, but now it’s nothing like before," he said. “Of course drug sales are happening on other dating apps, but at a fraction."

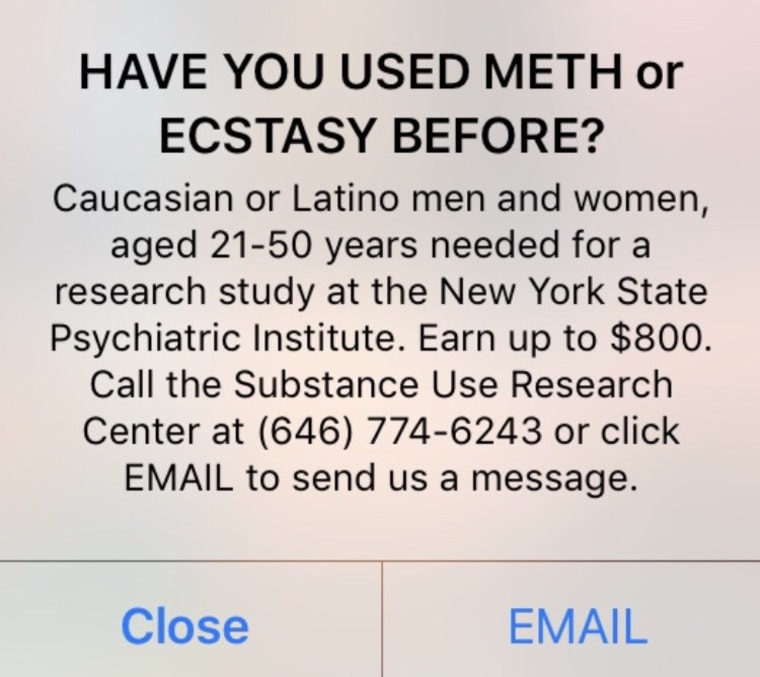

Jermaine Jones, a substance abuse researcher in Columbia University’s psychiatry department, said the combination of gay men’s disproportionate drug use and Grindr’s reputation as a “parTy and play” platform led him to use the app to recruit participants for a methamphetamine addiction study.

“Meth has been much more prevalent among LGBT people,” Jones noted. “When I started this study, I thought Grindr might be a good option, and so far it has actually been very successful.”

Jones said approximately 300 men responded to the ad he and his fellow researchers posted to Grindr.

According to data from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1.4 million people in the U.S. used methamphetamines in 2016, and gay men use the drug at double the rate of the general population.

“NO SUCH THING AS CENSORSHIP”

Despite the many gay dating apps through which he could potentially push his product, Mike, the New York drug dealer, said he exclusively uses Grindr.

“On Grindr, there’s no such thing as censorship,” he said. “I can post whatever I want.”

Based on his experience using the app to sell drugs for the past two years, Mike said “it doesn’t seem like Grindr’s policies enforce suspensions or permanent bans.”

“I had my profile flagged twice, but nothing ever happened,” he added. “I just received a warning that my account would be deleted, which never happened.”

NBC News spoke to several Grindr users who said they attempted to flag profiles of those selling or offering drugs, but to no avail.

“Grindr seems very unwilling to respond to any report requests for anything beyond underage users, whereas many of the apps will take action and remove users posting about drugs,” said Morgan Grafstein, 23, a Grindr user from Minneapolis.

“I will report users openly advertising drugs and recheck their profile 24 hours later and see no change,” he added.

Derrick Anderson, the Grindr user in Chicago, said the app’s administrators are not doing enough when it comes to policing drug activity.

“Reporting drug profiles never feels like it has an impact,” he said.

“GRINDR IS AN OPEN PLATFORM”

In late 2016, LGBTQ blog WEHOville reported that its two-month study of gay dating apps — including Scruff, Mister X and Surge — revealed “only Grindr allowed its users to openly include emojis and text in their profiles that indicated they were drug users or sellers.” A month after WEHOville’s report, Grindr appeared to have censored at least a few well-known drug emojis and words. Nearly two years later, however, the app’s drug market appears to be alive and well.

When asked about the continued use of Grindr for the buying and selling of drugs, a spokesperson for the company said, “Grindr prohibits the promotion of drug use in its user profiles and is committed to creating a safe environment through digital and human screening tools to help its users connect and thrive.”

“Grindr encourages users to report suspicious and threatening activities,” the spokesperson added. “While we are constantly improving upon this process, it is important to remember that Grindr is an open platform.”

The spokesperson did not respond to NBC News’ multiple requests for comment regarding specific actions Grindr has taken to reduce the sale and promotion of drugs on the app.

Under U.S. law, Grindr is not required to do anything when it comes to moderating drug-related content on its app. Like all websites and apps, the gay dating platform is protected by Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996. The legislation, passed in the early days of the internet, is known as one of the most important tech industry laws.

“Dating apps have no liability for any content that is posted on their platform by a third party,” Kai Falkenberg, a law professor at Columbia University, explained. “Any moderation that these sites are currently doing, they are doing it for the benefit of their business model but not out of any legal obligation.”

But while Grindr is not legally obligated to moderate drug content on its platform, some experts say it would be relatively easy to do so.

“If you know what the drugs are called, and you program words into the algorithm, like 'crystal meth' for example, it is very simple to detect those words,” David Fleet, a professor of computer science at the University of Toronto, told NBC News.

“It's very straightforward,” he added. “If the dating apps use modern machine-learning tools, not only can they censor pre-programmed words, but they could also detect other words that are essentially used as synonyms for various, more covert terms for drugs.”

While Grindr may not be policing drug activity on its app — real police are. There have been several examples in the past few years of men being arrested for selling illicit substances through the app.

One of those men is Harold Gondrez, 67, a bisexual man from Manhattan who was arrested in July 2016 after selling crystal meth to an undercover New York Police Department officer he met on Grindr.

“We talked and talked for several months,” Gondrez said, “and we built a friendship, or so I thought. At first I asked him if he was a cop, and of course he said no. Then two weeks after the last sale, a whole team of police officers came to my apartment to arrest me.”

Shortly after Gondrez was busted, a Virginia mayor abruptly resigned and pleaded guilty to offering meth to undercover cops he met on Grindr. And across the pond earlier this year, a U.K. man who was using Grindr to sell drugs was sentenced to nearly a decade in prison.

UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES

McCabe, president of the National Association of LGBT Addiction Professionals, said despite having no legal obligation, Grindr has a moral obligation to fight drug sales on its platform.

He acknowledged that “censoring drug content on Grindr wouldn’t eradicate the problem” of substance abuse in the LGBTQ community. However, he said the app creates a unique problem for those trying stop using drugs.

“Grindr could be a trigger for someone struggling with sobriety, especially in the early stages of recovery,” he explained. “If that’s the case, they need to remove those apps from their phone and make a commitment that they won’t go on Grindr.”

While research is limited, a 2017 study in Thailand concluded that gay dating apps “significantly increased motivational substance use through messaging from their counterparts.”

“Persuasion through dating significantly influenced people toward accepting a substance use invitation, with a 77% invitation success rate,” the report states. “Substance use was also linked with unprotected sex, potentially enhancing the transmission of sexually transmitted infections.”

Smith Boonchutima, one of the study’s authors and a professor at Bangkok’s Chulalongkorn University, said less frequent use of gay dating apps “resulted in less exposure to drugs.”

And while Grindr’s policy limits the app to those over 18, a study published earlier this year by the Journal of Adolescent Health found gay dating apps, like Grindr, are “not uncommon among” adolescent gay and bisexual teen males between the ages of 14 and 17.

Ethan said he fears the prevalence of drug promotion on Grindr and other gay dating apps has led to complacency within the LGBTQ community when it comes to illicit drug use — especially meth.

“Young adults use these more frequently and are being exposed to a heavy drug early on that it seems normal,” he said. “Obviously these drugs are addictive, so making it easy to get while downplaying the effects and consequences will ruin lives plain and simple.”