Scientists have used cloning technology to make stem cells from a woman with Type 1 diabetes that are genetically matched to her and to her disease.

They hope to someday use such cells as tailor-made transplants to treat or potentially even cure the disease, which affects millions and which now has few treatment options other than careful diet and regular use of insulin.

It’s the second report his month of success in using cloning technology to make human embryonic stem cells — the cells that eventually create a complete human being and that scientists hope to harness to treat diseases ranging from diabetes to Parkinson’s and injuries that cause paralysis or organ damage.

“I think this is going to become reality,” Dr. Dieter Egli of the New York Stem Cell Foundation, whose report is published in the journal Nature on Monday, told reporters. “It may be a bit in the future but it is going to happen.”

The technique they use is called somatic cell nuclear transfer — the same method used to make Dolly, the sheep who was the first mammal to be cloned, in 1996. Scientists remove the nucleus from a normal cell, clear the nucleus from a human egg cell, then inject the nucleus from the skin cell into the egg.

“I think this is going to become reality."

Various chemical or electrical tricks can be used to start the egg growing as if it had been fertilized by sperm. In this case, they used DNA from a woman with Type 1 diabetes, and they said they used an improved method to trick the egg into developing.

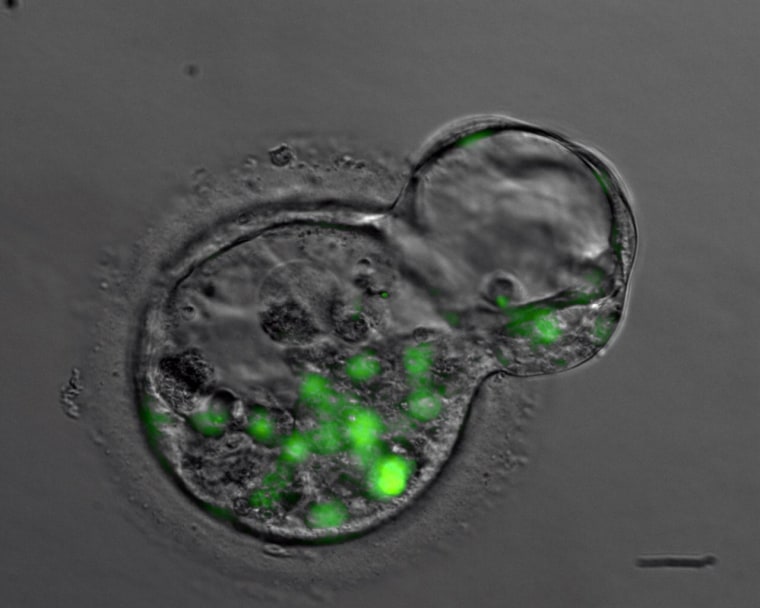

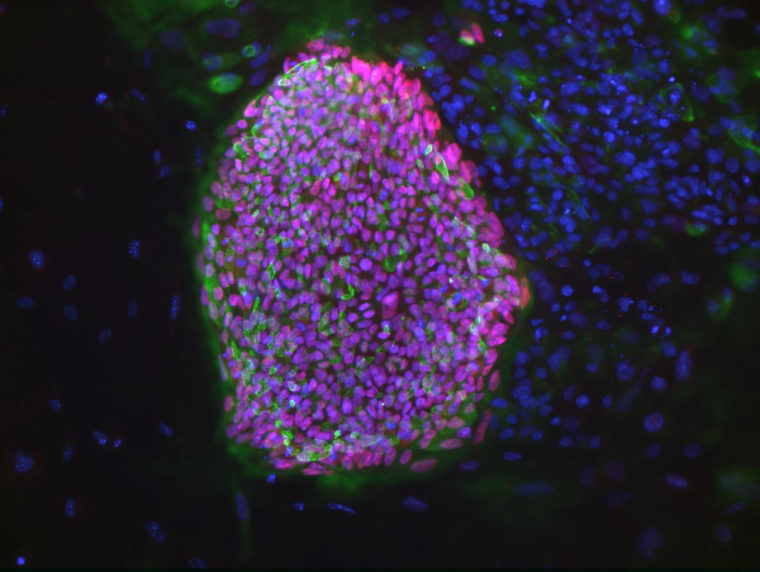

It got to what’s called a blastocyst — a ball of cells that has not yet begun to differentiate into the different types of cells and tissues in the body, such as nerve cells, blood cells and bone cells. They removed individual cells and used various chemical baths to direct them to form into the desired cell type — the beta cells in the pancreas that make insulin and that are destroyed in diabetes. These cells carry the patient’s own unique DNA, including whatever genetic mistakes led to her diabetes.

“These stem cells could therefore be used to generate cells for therapeutic cell replacement,” they wrote in their report.

Scientists have cloned sheep, pigs, mice and monkeys, but it’s been far harder to clone human beings. It’s partly because of the controversy — few people advocate cloning humans for the purpose of making babies, and many people object to destroying a human embryo, even one that only ever existed in a lab dish.

Years of legal fighting that went all the way to the Supreme Court restricted U.S. funding of this research. The federal government finally won its case but funding is still restricted, and most work is done by private groups such as the New York Stem Cell Foundation, or carefully firewalled labs at places such as Harvard University.

Even so, it’s difficult to make human embryonic stem cells and Egli’s is only the third lab to report having done so. Earlier this month, a team that included Massachusetts-based Advanced Cell Technology made cells by cloning two adult men, and last yeara team at Oregon Health & Science University used the technique to make cells from babies.

“I think these papers show conclusively it’s possible,” said Dr. Douglas Melton of the Harvard Stem Cell Institute, who was not involved in the research.

Melton’s and other groups have learned how to “trick” ordinary skin cells into acting like embryonic stem cells. These so-called induced pluripotent stem cells, iPS cells for short, might also someday be used to grow transplants perfectly matched to a patient. But again, the technique isn’t easy and there have been many stumbling blocks.

Another barrier — human eggs are not easy to come by and there are also ethical questions about whether women should be paid to donate their eggs for this kind of research. The women in Egli’s study were paid for egg cells left over from infertility treatment efforts.

Egli and the other teams that have succeeded in using this technique say some women’s egg cells seem to work better than others. They are not yet sure why, although eggs from younger women appear to transform a little more efficiently, Egli says.

The next step is to transplant the pancreatic cells into mice to see if they grow into normal human beta cells, Egli says. To test the method on humans requires Food and Drug Administration approval.

“A person that has type-1 diabetes can reject and has rejected their own beta cells."

Melton, who’s been studying diabetes for decades, says it’s unlikely stem cell transplants will cure or treat diabetes, however. “A person that has Type 1 diabetes can reject and has rejected their own beta cells,” Melton told NBC news. “Making beta cells from these kinds of stem cells will not solve the problem.” But studying stem cells made from a patient with diabetes will be valuable for better understanding the disease, he said.

And the need is pressing. There are more than 2 million people in the United States alone with Type 1 diabetes. It’s caused when the body mistakenly attacks the beta islet cells that make insulin, destroying them. “We think that Type 1 diabetes may be a particularly good target for development of cell therapies,” said Egli.

“In 2005 when I co-founded the New York Stem Cell Foundation, the idea was to find better treatments and, hopefully, a cure for diabetes,” added the organization’s Susan Solomon.

Almost all scientists working with embryonic stem cells say they want to study diseases and cures, not make babies. Many studies have shown that farm animals creating using cloning technology are often abnormal and many die prematurely.

Egli agrees it would be wrong to use the technique to try to make babies. “This should not be done. It would be very irresponsible," he said.