Researchers say they are homing in on the particular gut microbes that can make you fat, or keep you free of irritable bowel disease. Their goal? Maybe infusions of good, clean germs to treat disease.

They found a set of bacteria that seem to help control how much fat the body layers on, and a separate set that affect the immune system. And they think they’ve got a system for testing which bacteria, out of hundreds of species living in the gut, might be important for health.

“We can culture these organisms, manufacture these organisms in pure form … so they could be administered to individuals in the future,” says Dr. Jeffrey Gordon of Washington University in St. Louis, who led the research team.

“We could generate a 21st-century medicine cabinet ,” he added.

Writing in the journal Science Translational Medicine, the researcher said they used specially bred sterile mice and poop donations from five healthy adults to identify particular species of bacteria that regulate helpful immune system cells called regulatory T-cells, and that helped mice put on a layer of body fat.

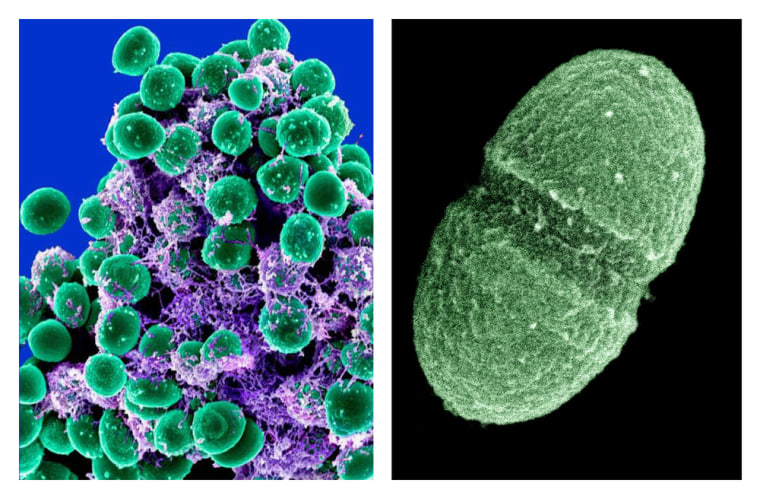

Every human carries pounds of microorganisms on our skin and in our guts that we couldn’t live without. They break down food, prevent infections and extract nutrients like vitamin K. Scientists believe at least 10,000 different species live in and on us, with hundreds of species and trillion of individual bacteria in our digestive systems.

Some studies also show they may affect our weight, by helping convert food to fat or by passing it along quickly before the body absorbs too many calories. They also may affect diseases such as Crohn’s disease and irritable bowel syndrome by altering the balance of regulatory T-cells.

Fecal transplants can help beef up a patient’s gut microbiome and cure a deadly diarrheal infection called Clostridium difficile, which kills more than 14,000 people in the United States every year. They can affect metabolism, and Gordon’s team has already shown that bacteria from obese humans made mice pack on fat.

“We developed a new way of sorting through populations and identifying the responsible organiams, the key actors,” Gordon said in a telephone interview.

In one experiment, the team identified eight different species of bacteria from lean, healthy women that made the mice put on fat. “We started out with a sterile mouse,” Gordon said. They knew germ-free mice are always skinnier than mice with a normal load of gut bacteria.

It’s hard to tell if the mice actually put on weight – they were growing anyway – but they put on a clear layer of fat after getting the purified human bacteria, even as they ate exactly the same food as other mice that didn’t get the bacteria and that stayed lean.

The bacteria that help mice gain weight includes species called Bacteroides intestinalis, B. ovatus, B. vulgatus, B. caccae, and B. thetaiotaomicron.

The team also identified a species of bacteroides that seemed to help the mice produce more regulatory T cells – something that in people should help protect against inflammatory diseases such as Crohn’s disease, irritable bowel syndrome and perhaps even some effects of diabetes.

Gordon’s team had earlier shown that people appear to have their own unique populations of bacteria, and that they pretty much keep the same distribution through life.

But they and others have also shown it’s possible to change the makeup, at least a little, through diet. “We know that diet is a huge driver in the activity of the gut community,” Gordon said.

So if scientists can identify the best bacteria for keeping people lean and healthy, they can at least diagnose illness by testing for those species, and perhaps find ways to change the balance.

“There is not a single magic organism that has the power the regulate the body,” Gordon cautions. It’s more likely to be a combination that works. In the meantime, while fecal transplants are definitely shown to cure C. difficile infections , Gordon does not recommend clinics that claim to treat weight loss with poop transplants from slim people.

· Follow NBCNewsHealth on Facebook and on Twitter