The day begins before dawn for the nuns, who reserve the first hour for quiet prayer before the morning takes hold and the warmth of the rising sun stirs the birds to sing.

Sister Therese Durge of the Infant Jesus, 89, awakens in her small cell. The 8-by-10½-foot room contains a wooden bed and firm mattress, a metal press for clothing, a wooden desk for writing and a wooden dresser. Each sister lives in a similar cell.

Sister Therese opens the chapel at 5:30 a.m. for two parishioners who pray every day before they go to work. Then she prays.

This is the peaceful rhythm of life at the Monastery of the Discalced Carmelite Nuns.

Chastity, poverty and obedience

The order began on Mount Carmel in Israel during the 12th century, initially a group of hermits striving for a life of solitude and prayer. The same goals guide Carmelite nuns today. Their monasteries are enclosed by walls, creating conditions for a life of continual silent prayer.

Vows of poverty, chastity and obedience to the Catholic Church bind the sisters of the Discalced (barefoot) Carmelites, founded by St. Teresa of Ávila, a Carmelite nun in the 16th century.

After the second Vatican Council, in the mid-1960s, church leaders in Rome made it possible for religious communities to re-evaluate how they wanted to live. And gradually, some Carmelite nuns, like those in Elysburg, have ventured into the chapel for a daily Mass with the outside community. They believe this outreach allows them to elevate more souls through prayer.

Venturing outside

Sister Angela Pikus of the Eucharist, the 68-year-old prioress at Elysburg, even got her first driver’s license last year. Her mission: to drive down the hill in the monastery’s 1998 blue Toyota Corolla to get Sister Etheldreda Kilbarger of the Infant Jesus her heart medicine and to visit others sisters in the hospital.

“It was something I had to do,” said Sister Angela.

“Every time I go in the car I offer a prayer for safety. You know how driving can be,” said the prioress, who knows that the group of 13 nuns, 10 of them over 75, depend on her.

She and Sister Alberta Grimm of the Blessed Sacrament, 90, cared for Sister Etheldreda through years of illness until Sister Etheldreda died at age 96 in August, saying she was ready to go to heaven.

“My mother must be wondering where I am,” she told those taking care of her.

Sister Etheldreda is buried behind the monastery with the other sisters who have gone before. She had given herself to God in 1934 when her name was Helena Kilbarger. Back then, religious vocations were more common and parents knew children joining orders would be cared for in the church.

A 'satisfying life'

Today, the sisters wait to see what will become of their order. There are no young nuns, but they trust in God and pray.

Brother Paul Bednarczyk C.S.C, executive director of the church’s National Religious Vocation Conference in Chicago, says the Elysburg monastery is an example of a broad trend. Though the tradition of religious life it carries on will not die out, he said, “It will be much smaller.”

Smiling, Sister Josephine Koeppel of Saint Theresa, 84, said: “I have everything I had before and everything I thought I was missing. It is a totally satisfying life. I just wish it were possible for young people to know that God put someplace on the world, a place where you can really be totally satisfied.”

Every minute of daylight is accounted for in the nuns’ rotating system of chores — preparing meals, washing dishes, cleaning, phone duty, correspondence, preparing the chapel for daily Mass, shipping altar breads to parishes and cutting the grass.

Still, quiet prayer is each day’s goal.

An hour with the community

After praying for an hour alone, all sisters who are able gather for morning praise at 7:30 a.m. They sing and give thanks for their blessings. They pray silently together.

At 8 a.m., a Mass in the chapel is said by Rev. Robert Plociennik, a Franciscan friar from Shamokin, Pa.

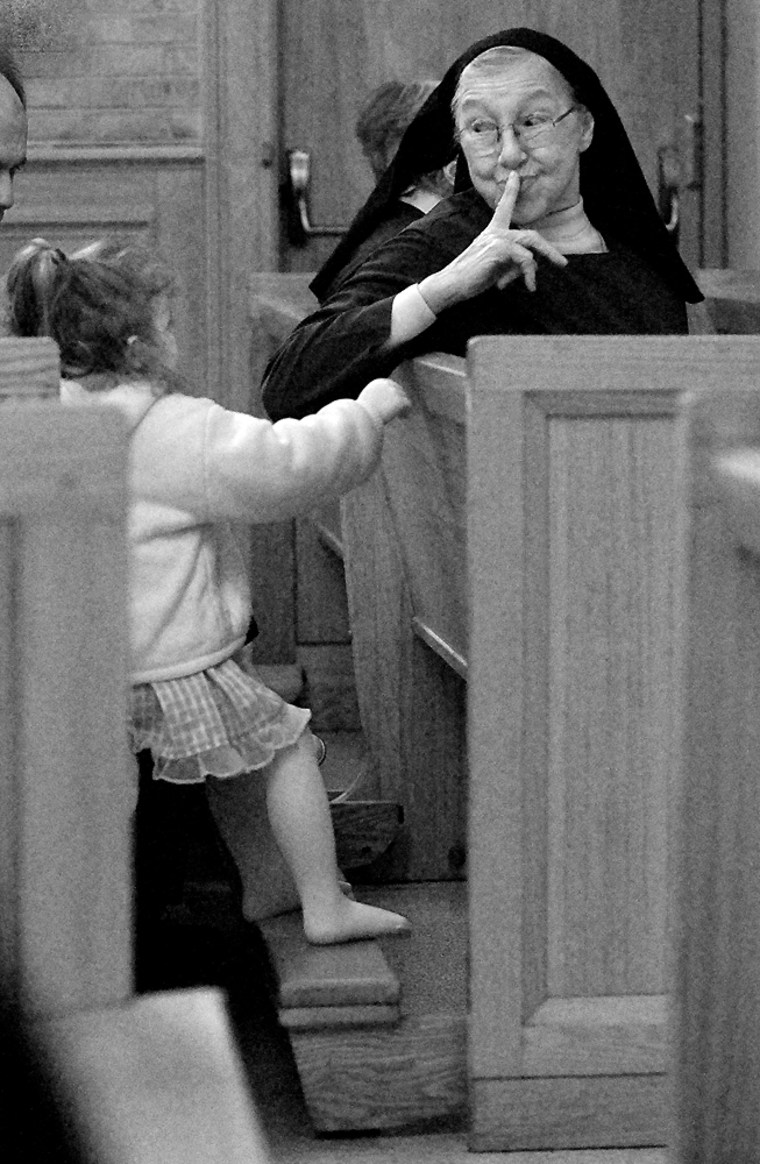

People from surrounding communities are welcome for the hour. Steve and Michele Resuta of Elysburg bring their five children every day. They all love the sisters.

The faithful consider the Carmelites’ prayers for one’s family a powerful blessing.

The bell rings at 11:40 a.m. to call the sisters for midday prayer and examination of soul and conscience.

They read aloud Psalm 146: “Let us serve the Lord in holiness all the days of our life.”

The main meal of the day is at noon. Creamed tuna over white rice is a common dish, with green beans and salad. The lettuce comes from a farmer down in the valley. Fruit and sweet pastries are gifts from a friend.

One hour to talk

The sisters do not speak during meals but listen to scriptures and sermons from an old cassette player in the dining room.

Their duties are done in silence when possible until the bell rings again, calling them to evening praise 4:45 p.m.

Private prayer is followed by a light supper at 6 p.m.

An hour of recreation starts at 6:45, after supper and readings. Some sisters bring mending while others put their feet up and talk about topics from faith to the birds on the feeder outside the kitchen window.

They gather one more time to pray at 8:15 p.m., before it’s time for bed.

It’s still inside the enclosure. The faint sounds of the elderly nuns on the move fill the buildings. Canes lightly tap as feet shuffle; power scooters hum. Walkers with Gatorade-green tennis balls on the feet slide along linoleum-covered halls.

“We don’t retire,” explains Sister Angela. “Prayer is the first work and you don’t stop that.”