He was a sickly boy, often bedridden with tuberculosis, who passed the time with fantastical stories by Jules Verne and H.G. Wells that made his mind imagine otherworldly exploration.

But for Robert Goddard, who would become the founding father of rocket science decades before humans were sent to the moon, traveling to places far from Earth wasn't just the stuff of fiction.

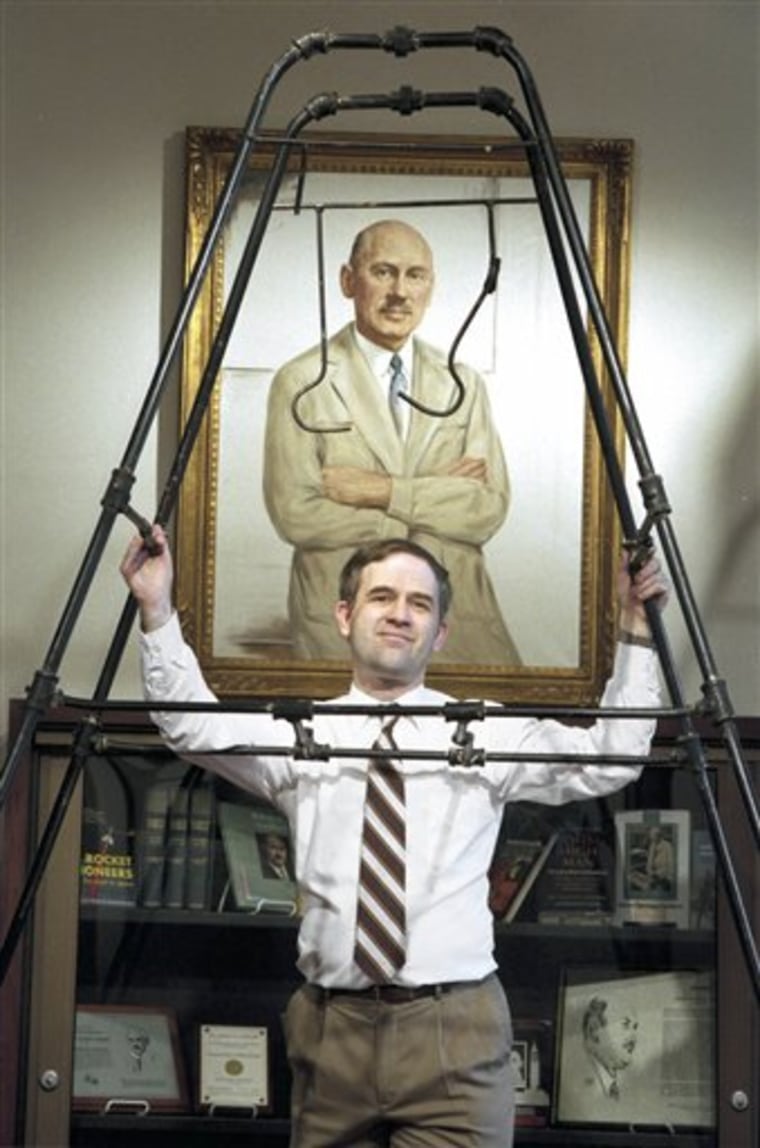

In "Lift Off: Reaching for the Stars," an exhibit on display at the Worcester Historical Museum through July 22, Goddard's influence on space travel is traced with photos and a narrative timeline from his boyhood dreams in Worcester to the science he developed to make them happen.

In 1899, Goddard became convinced it was possible to blast a rocket into space, and began pursuing physics to prove his theory. He was 17.

"Everyone thought he was nuts," said Vanessa Hofstetter, the museum's exhibit coordinator. "He thought you could aim a rocket at the moon and it would get there."

Formula for liquid fuel

Through his research as a student and professor at Worcester Polytechnic Institute and Clark University, Goddard came up with a formula for liquid fuel — which he figured would be more powerful than gunpowder — that could propel a rocket into space.

The scientific papers he started publishing attracted attention from the media, which quickly dismissed Goddard as a mad scientist without a prayer of proving his theories.

"The thing that really comes to mind when thinking about Robert Goddard is his determination and his focus," said Mott Linn, Clark University's archivist. "He decided to become a physicist because he wanted to pick the discipline that would help him the most in shooting an object into outer space. It became the No. 1 driving force in his life. How many people have that focus?"

But before his success, there were more than a few stumbles.

Goddard launched his first rocket in 1926 on his aunt's farm in nearby Auburn.

The 10-foot-long, six-pound projectile of metal tubing shot up 41 feet and arced out 184 feet before crashing in a cabbage patch.

Total flight time: three seconds.

Rattled the neighbors

A few more test flights crashed and burned, but the most harrowing of the rocket launches was the fourth one. Back on his aunt's farm in 1929, the episode created such a violent detonation that it shook nearby homes and frightened residents with balls of fire, plumes of smoke, and a crash that had some thinking an invasion was under way.

But the incident didn't seem to rattle Goddard. A photo shows him standing over the decimated projectile with a grin that makes him look downright giddy.

The state fire marshal wasn't as amused, and banned Goddard from performing any more launches in Massachusetts. The exile led him to start experimenting on federally owned land at the Fort Devens military base, where the state had no control over his launches.

Funding his research through money he received at Clark, the professor's work soon attracted the interest — and money — of industrialist Daniel Guggenheim in the early 1930s. With a four-year annual grant of $25,000 from Guggenheim, Goddard and his wife moved to Roswell, N.M., to continue developing his rocket science.

By 1943, he had been hired by the Navy to work on rocket-assisted takeoff for airplanes near Annapolis, Md.

The exhibit's focus on Goddard ends with his death, from larynx cancer at age 63, in 1945.

"You'd be overstating it to say he was famous at the time," Linn said. "The United States getting into rocketry was still a decade away."

Goddard's legacy

But his work had an undeniable impact that would become widely recognized. A few days before the first manned moon landing in 1969, The New York Times ran a correction about a story they published 49 years earlier, mocking Goddard's theories.

The museum's exhibit also explores Goddard's legacy. NASA photographs taken from outer space show different landscapes across Earth — from the arm of Cape Cod muscling its way into the Atlantic to what looks like a cluttered mass created by the Himalayan mountains.

The display ends with Worcester's contributions to space travel. Most notable is the nod given to the David Clark Company, which started as a small knitting business that was tapped to make spacesuits for NASA.

"That's all thanks to Robert Goddard," Hofstetter said.