HOUSTON - For a routine orbital boost last week, the international space station pulled off a new trick that significantly enhances the outpost's operational flexibility and safety. Experts at Russian Mission Control successfully ignited a set of maneuvering thrusters that had not been used for seven years — and that had refused to fire in several previous attempts.

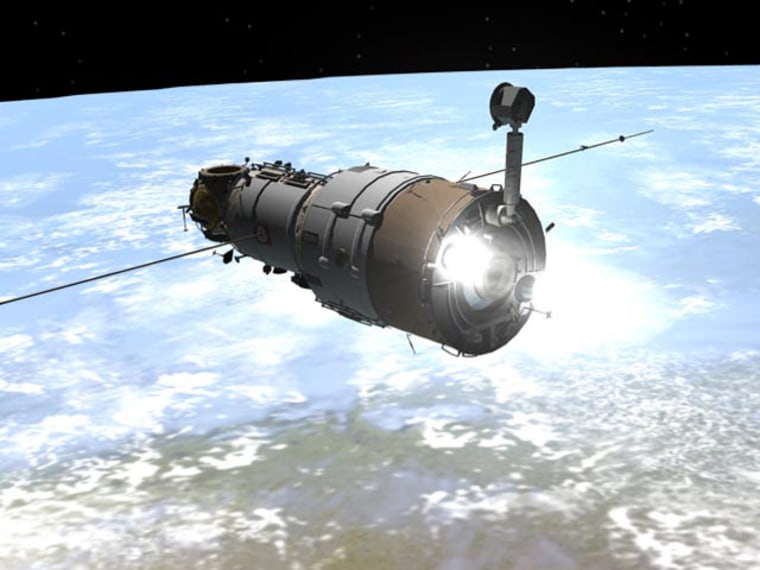

Mission Control's Nikolai Kryuchkov said controllers decided to use the station's main engines on the Russian-built Zvezda service module for last week's boosts —rather than following the usual routine, which relies on the smaller thrusters on a docked Progress cargo craft. The big engines were previously used when Zvezda docked with the station's earliest modules, back on July 24, 2000.

"The fact that the Russian engines operated well now proves their high reliability and long service life,” Kryuchkov said.

Having those main engines working will be increasingly important in the years ahead, Susan Brand, NASA’s manager for the current space station expedition, told MSNBC.com in an e-mail.

She acknowledged that the station's orbit could get a boost from Russian Progress ships as well as the European Space Agency's Automated Transport Vehicles, which are due to enter service this year.

“However, in the process of managing and planning all of the vehicle traffic to the ISS, there will be more frequent and longer time periods that no vehicle will be docked to the aft end of the service module,” she continued. “During these time periods, reboost capability will be available using the service module thrusters. These service module reboost tests reconfirm the performance of these engines to support future operations.”

Why those boosts are neede

Reboosting is performed both to line up the station’s orbit for future visits and on occasion to dodge a too-close predicted space debris fly-past. In the past, docked shuttles used surplus maneuvering fuel to push the station upward, but changes in the station’s size and location of docking ports have basically eliminated that option.

Slideshow 12 photos

Month in Space: January 2014

Firing these two engines, which are positioned 180 degrees apart near the outer rim of the Zvezda's service module’s aft end, was made possible by the absence of a transport vehicle docked to the port there. A Soyuz carrying the station's returning Expedition 14 crew and space passenger Charles Simonyi had undocked a week earlier, and the next robot supply ship is scheduled to arrive on May 15.

Both engines were first test-fired for 30 seconds last Wednesday. That cleared the way for an 80-second firing on Saturday.

The previous “oldest engine” firing had been 20 years ago, when thrusters of the same design were installed aboard the Salyut 7 space station, launched in April 1982. They were last used four years later during a joint maneuver with the just-launched Mir station.

Requalifying the engines for continuing use on the international space station, and conducting operational firings over the next five to 10 years, will extend their certified lifetime significantly. For Earth orbit missions, alternative thrusting is almost always available from docked supply ships, but it is reassuring to now have the ability to perform an “anytime” debris avoidance burn when such a ship is not docked to the station.

The biggest benefit has to do with developing long-term certification for such thrusters on interplanetary missions of the future.

Previous frustrations

The thrusters provide eight times the push that the smaller Progress engines provide, but the acceleration is still so small as to be practically unnoticeable inside the station. There were no known crew reports describing any feelings, or any sound, or sight out the windows, associated with the firings.

An attempt to test-fire the pair of engines on April 18 last year was aborted at the last minute when one of the protective covers failed to open fully, due to physical interference from an antenna placed there by spacewalkers in 2003. Astronaut Mike Fincke, who made that spacewalk with his cosmonaut colleague Gennady Padalka, later explained that the antenna was installed in support brackets that made sure it was in proper position — but the position had apparently been measured incorrectly by engineers at the spacecraft factory.

Late last year, that antenna was moved during another spacewalk. But whether that was the only problem remained to be tested.

Real redundancy

The frustrations and ultimate success of this operation further underscore some key principles of operating a big space station in orbit:

- The station has grown too complex and has undetectably diverged too far from ground documentation to ever expect all ground-planned processes to work as designed. Surprises, and sometimes unpleasant surprises, will occur with growing frequency, and the only workable approach is to make plans based on such guaranteed uncertainties.

- Because the space station is on a long-term series of expeditions rather than a short-term dash, there is usually enough time to react to such surprises with tools and techniques at hand, or quickly developed.

- The long-term certainty of hardware breakdowns and operator errors means that redundancy in critical capabilities — such as an extra thruster system, an extra spacesuit and air lock system, an extra oxygen system — has proven far more valuable than the station’s designers had originally expected. This is especially true when the redundant systems aren’t simply "extra copies" of one design, but are based on different engineering principles, even on hardware from different nations.

- For decades humans have operated in Earth orbit, where resupply is feasible, spare parts and new tools can be delivered, and emergency landing always an option. The transition in operational and design concepts to missions to the moon and beyond absolutely requires developing and trusting hardware for very, very long lifetimes (and multiple repairs) in space. There may be a lot of space out there, but there is only one place where such hardware can receive the required testing and validation: the international space station.

That’s the context of past, present, and future for this otherwise-routine space technology demonstration. Firing these long-unused rocket engines and adding them back into the "hip pocket" of available capabilities at the space station is another step in that direction.