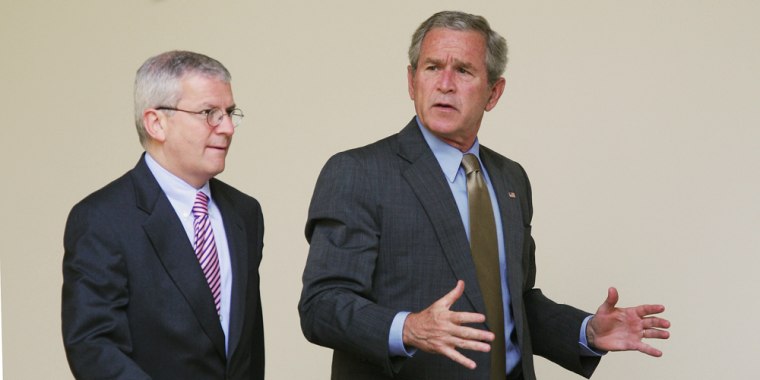

The House Judiciary Committee voted contempt of Congress citations Wednesday against White House Chief of Staff Josh Bolten and President Bush’s former legal counselor, Harriet Miers.

The 22-17 vote, which would sanction the pair for failure to comply with subpoenas on the firings of several federal prosecutors, advanced the citations to the full House.

A senior Democratic official who spoke on condition of anonymity said the House itself likely would take up the citations after Congress’ August recess. The official declined to speak on the record because no date had been set for the House vote.

Committee Chairman John Conyers said the panel had nothing to lose by advancing the citations because it could not allow presidential aides to flout Congress’ authority. Republicans warned that a contempt citation would lose in federal court even if it got that far.

The drive to pass the citations on to a federal prosecutor comes after nearly seven months of a Democratic-driven investigation into whether the U.S. attorney firings were directed by the White House to influence corruption cases in favor of Republican candidates. The administration has denied that, but also has invoked executive privilege on internal White House deliberations on the matter.

White House counsel Fred Fielding had said previously that Miers and Bolten were both absolutely immune from congressional subpoenas — a position that infuriated lawmakers.

“If we countenance a process where our subpoenas can be readily ignored, where a witness under a duly authorized subpoena doesn’t even have to bother to show up, where privilege can be asserted on the thinnest basis and in the broadest possible manner, then we have already lost,” Conyers, D-Mich., said before the vote. “We won’t be able to get anybody in front of this committee or any other.”

The panel’s vote is the first step on the road to a possible constitutional showdown in federal court.

Deal, or no deal?

If history and self-interest are any guide, the two sides will resolve the dispute before then. Neither side wants a judge to settle the question about the limits of executive privilege.

But no deal appeared imminent. Fielding has offered to make top administration officials available for private, off-the-record interviews about the administration’s role in the firings. But he has invoked executive privilege and directed Miers, Bolten and the Republican National Committee to withhold almost all relevant documents. Miers did not even appear at a hearing to which she had been summoned, infuriating Democrats.

Democrats rejected Fielding’s “take-it-or-leave-it” offer and advised lawyers for Miers and Bolten that they were in danger of being held in contempt of Congress.

If the citation passes the full House by simple majorities, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi then would transfer it to the U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia. The man who holds that job, Jeff Taylor, is a Bush appointee. The Bush administration has made clear it would not let a contempt citation be prosecuted because the information and documents sought are protected by executive privilege.

The Justice Department reiterated that position in a letter to Conyers on Tuesday. Brian A. Benczkowski, principal deputy assistant attorney general, cited the department’s “long-standing” position, “articulated during administrations of both parties, that the criminal contempt of Congress statute does not apply to the president or presidential subordinates who assert executive privilege.”

Benczkowski said it also was the department’s view that the same position applies to Miers.

Power to commute or pardon

Contempt of Congress is a federal crime, but a sitting president has the authority to commute the sentence or pardon anyone convicted or accused of any federal crime.

Congress can hold a person in contempt if that person obstructs proceedings or an inquiry by a congressional committee. Congress has used contempt citations for two main reasons: to punish someone for refusing to testify or refusing to provide documents or answers, and for bribing or libeling a member of Congress.

The last time a full chamber of Congress voted on a contempt citation was 1983. The House voted 413-0 to cite former Environmental Protection Agency official Rita Lavelle for contempt of Congress for refusing to appear before a House committee. Lavelle was later acquitted in court of the contempt charge, but she was convicted of perjury in a separate trial.