The United States has assembled an imposing industrial army in Iraq larger than its uniformed fighting force and responsible for a such a broad swath of responsibilities the military might not be able to operate without its private-sector partners.

More than 180,000 Americans, Iraqis, and nationals from other countries work under a slew of federal contracts to provide security, gather intelligence, build roads, forge a financial system and transport needed supplies in a country the size of California.

That figure contrasts with the 163,100 U.S. military personnel, according to U.S. Central Command in Tampa, Fla., the organization responsible for military operations in the Middle East. The Pentagon puts the military figure at 169,000. There are another 12,400 coalition forces in Iraq.

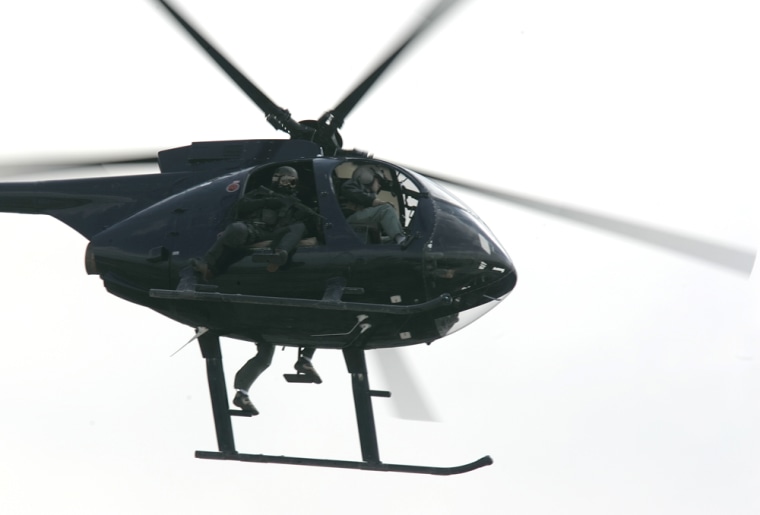

But it has its dangers. Employees for Blackwater USA were involved in a weekend shooting that left 11 Iraqis dead.

The heavy reliance on contractors in a war zone is partly the result of a post-Cold War shrinking of the armed forces and the Bush administration’s preference for contracting out government functions to the corporate world.

It’s also due to the compressed nature of the war in Iraq. Combat operations are ongoing at the same time as the reconstruction of Iraq’s infrastructure and assorted economic development efforts, pushing the number of contractors to high levels.

While having contractors on and around the battlefield is not new, the situation in Iraq raises questions about whether U.S. troops have become so dependent on contract help they could not function properly in their absence.

“If the contractors turn tail and run, we’ve still got to be able to fight,” said Steve Schooner, co-director of the government procurement law program at George Washington University and a former military lawyer.

Blackwater incident raises questions

The presence of thousands of private sector security guards adds another component to the debate. Employees for Blackwater and other companies are engaging the enemy in combat, a sharp departure from previous conflicts.

“It’s pretty clear that line has been crossed in Iraq,” Schooner said. “And it’s been crossed because we don’t have enough horses left, and we have all kinds of problems in terms of coordination.”

As the military leans on the private sector, there’s a push to hold contract employees to the same legal standards as military personnel.

A measure proposed by Rep. David Price, D-N.C., would require all government contractors to be covered by federal criminal codes, a shortcoming revealed by the conflict in Iraq. Presidential candidate Barack Obama, D-Ill., is promoting similar legislation in the Senate.

“One suspects that contractors are being used to mask the true extent of our involvement in Iraq,” Price said in an interview Wednesday. “How else are you going to interpret it when the number of contractors exceeds the number of troops?”

War being outsourced?

Groups representing federal contractors rejected the idea the war is being outsourced.

“In Iraq we’re doing something that’s never been done before — there’s three concurrent missions going on,” said Stan Soloway, president of the Professional Services Council in Washington.

“Normally this would be a sequential process. You achieve a degree of security and then you start reconstruction and then you build the infrastructure. But it’s all being done at the same time, which is one of the reasons the number (of contractors) is so high.”

Where contractors hail from

According to Central Command, there are 137,000 contractors working in Iraq under Defense Department contracts and almost half of those are Iraqis. More than 22,000 are U.S. citizens and the remainder hail from other countries. Close to 7,300 are security workers.

Under separate contracts, the State Department and U.S. Agency for International Development employ thousands more workers, including security guards.

State Department spokesman Sean McCormack said Monday the department does not release the number of contract employees due to concerns their safety could be compromised.

However, a July report from the Congressional Research Service said the State Department has hired over 2,600 private guards to protect U.S. diplomatic personnel and to guard the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad as well as other key sites inside the city’s “Green Zone.”

The Agency for International Development has more than a dozen contracts and grants for services from electrical power generation to sanitation to water supply. There are 3,200 contractors helping to manage these projects, which have employed more than 50,000 Iraqis, according to USAID’s public affairs office.

Pentagon: Contractors fill necessary roles

Pentagon spokesman Bryan Whitman said Wednesday that military contractors fill necessary roles but ones that would distract combat troops from their primary mission.

“You don’t necessarily need to take a rifleman and turn him into a cook if you can contract for a cook,” he said.

Angela Styles, director of the Office of Federal Procurement Policy at the Office of Management and Budget from 2001 to 2003, said the challenge is determining where to draw the line.

If it is strictly a combat operation, the military can sustain itself, she said. In Iraq, where several missions are jumbled together and call for skills the armed forces don’t have, the answer is different.

“Could the military function without contractors on a sheer military mission? I think so,” Styles said. “But could they in a reconstruction mission? No.”