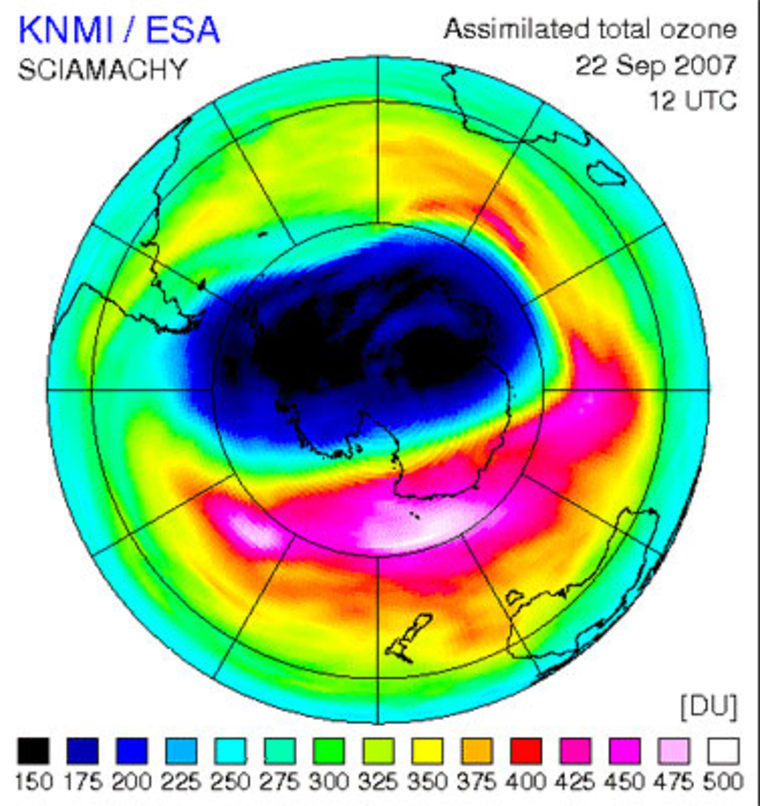

The gaping hole in Earth's ozone layer has shrunk 30 percent in size compared to last year, according to new measurements made by the European Space Agency's Envisat satellite.

The ozone layer loses about 0.3 percent of its mass annually, yet fluctuates in its thinness through the year. The region of extremely reduced ozone above Antarctica, popularly known as a "hole," generally peaks in size during September and October but regains its composure by the New Year.

Researchers are not certain if this year's smaller ozone hole means the radiation-blocking layer is healing.

"Although the hole is somewhat smaller than usual, we cannot conclude from this that the ozone layer is recovering already,” said Ronald van der A, a senior project scientist at the Royal Dutch Meteorological Institute in the Netherlands.

This year, the ozone region over Antarctica dropped 30.5 million tons, compared to the record-setting 2006 loss of 44.1 million tons. Van der A said natural variations in temperature and atmospheric changes are responsible for the decrease in ozone loss, and is not indicative of a long-term healing.

"This year's ozone hole was less centered on the South Pole as in other years, which allowed it to mix with warmer air," van der A said. Because ozone depletes at temperatures colder than -108 degrees Fahrenheit (-78 degrees Celsius), the warm air helped protect the thin layer about 16 miles (25 kilometers) above our heads.

While strides have been made to ban ozone-munching compounds, such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), the ozone layer continues to thin since the problem was widely recognized in 1985. The layer helps absorb harmful ultraviolet radiation from the sun, which increases the health risks of skin cancer and cataracts, as well as poses harm to marine life.