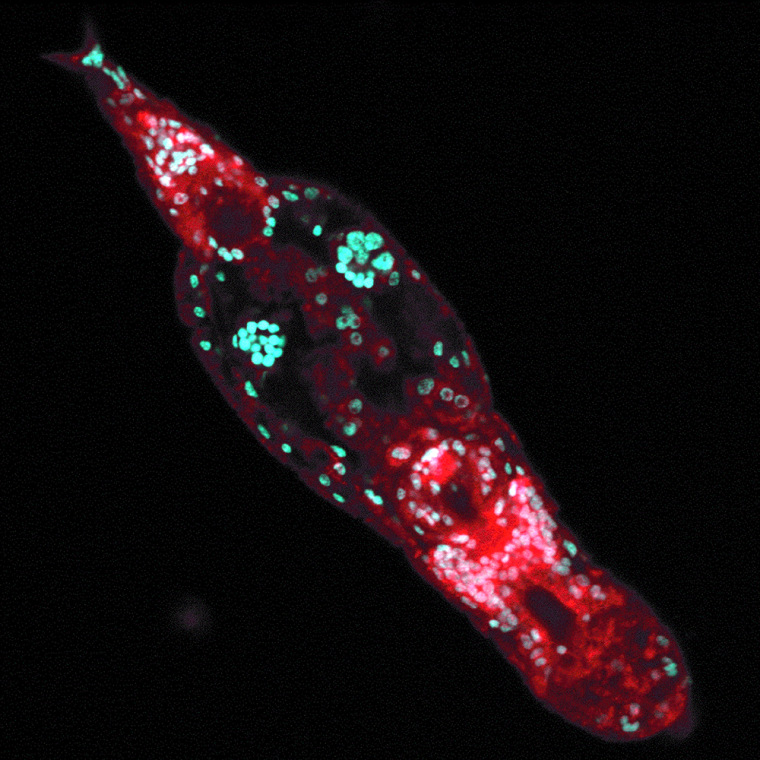

One microscopic organism has thrived despite remaining celibate for tens of millions of years, thanks to a neat evolutionary trick, researchers say.

Asexual reproduction has allowed duplicate gene copies of the creatures — called bdelloid rotifers — to become different over time. This gives the rotifers a wider pool of genes to help them adapt and survive, the researchers reported in Friday's issue of the journal Science.

“It is like having a bigger tool kit,” Alan Tunnacliffe, a molecular biologist at the University of Cambridge, said in a telephone interview. “You can do the same job, but better.”

The study builds on research published in PLOS Biology back in March, indicating that the translucent, waterborne creatures multiplied by producing eggs that are genetic clones of the mother. The earlier research also found evidence that the rotifers had adapted to changes in the environment over the species' 40 million years of existence.

That raised a puzzling question: How could the rotifers' genes adapt without the gene-swapping made possible by sexual reproduction?

“Sexual reproduction is supposed to be a good thing in evolution,” Tunnacliffe said. “So when you come across an organism like the bdelloid, which hasn’t engaged in sexual reproduction for tens of millions of years, you begin to question why sex is important.”

Every species of plant and animal that reproduces sexually has pairs of genes nearly identical to each other, with one of each pair coming from the mother and father. These creatures get around that problem with an evolutionary trick that allows their genes to drift apart and evolve on their own, after using molecular cloning techniques, Tunnacliffe said.

“No sex means the genes can evolve in different directions,” he said. “It is like you have a bigger gene pool to select from for different functions in evolution.”

The theory of natural selection says sex mixes up the genes to cope with unexpected changes in a treacherous world. Some genetic changes are good and boost survival — for example, against new strains of disease — but others lead to conditions such as cystic fibrosis in humans.

This report includes information from Reuters and msnbc.com.