It was a day that churned the stomachs of sports apparel and shoe executives.

One of the National Football League’s best-known players, Atlanta quarterback Michael Vick, was indicted on federal dog-fighting charges this summer. Companies from Nike to Reebok had developed shoes and jerseys bearing the athlete’s name. Upper Deck had sold Vick memorabilia at its online store. Because of the scandal, the products — which once generated millions of dollars in sales — were halted, including a new Nike shoe ready

to debut.

Ketchum Sports Network Vice President Kerry Slatkoff said she had never seen a reaction as severe as the one companies made after allegations about Vick were made public.

”Everyone said, ‘We’re done, we’re out,’ ” Slatkoff said. “Usually, they let it get quiet and make a decision down the road.”

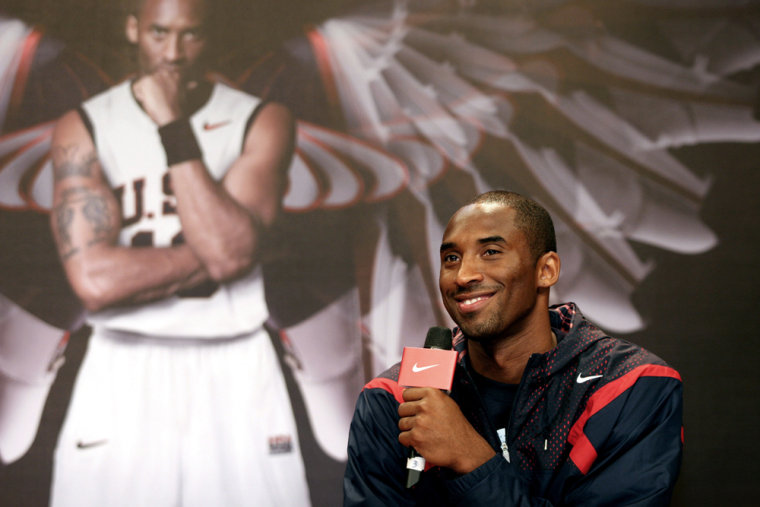

Pro athlete scandals have rocked sports the past few years. Before Vick’s fall from grace, there were sexual assault charges against Los Angeles Lakers star Kobe Bryant. New York Knick Stephon Marbury was horrendously portrayed in the recent sexual harassment case against team executive Isiah Thomas. One thing these disgraced athletes all had in common: An apparel and/or footwear line emblazoned with their name.

Which begs the question why do companies continue to base product lines on the reputation of pro players, even though their lives can’t be monitored 24/7 and their off-the field behavior can spur awful headlines?

Answer: Billions of dollars are at stake. According to NPD Group research, apparel sales made up about $50 billion, or 44 percent, of the global sports market last year, and they are on the rise, jumping 8 percent in 2006 in the United States alone. Athlete apparel lines comprise a healthy chunk of that market, and the appeal of stars to impressionable kids and teens is hard to beat.

Consider: The Air Jordan line put Nike on the map. And despite some troubles — Jordan had some gambling issues during his sterling NBA career, for instance — his peccadilloes never seemed to hurt sales. By the time he retired from the Bulls for the second time in 1998, Jordan shoes and apparel had already amassed more than $2.5 billion in sales for Nike. Gatorade and Tiger Woods struck a deal last week in which the PepsiCo division will create a special line of three sports drinks bearing the golfer’s name. GolfWeek reported Woods will pull in about $100 million from that deal, and sales will likely be quite a bit more.

The marketplace for products graced with the names of pro athletes is crowded, especially for basketball shoes. Chicago center Ben Wallace and Marbury both have their names on shoes selling for $14.95, while at the top prices, the likes of Bryant, LeBron James and others battle it out. In fact, to stand out among many athlete lines, Nike is promoting Bryant and James in a relatively untapped part of the world for such apparel: China. Nike just introduced an edition of the Cleveland Cavalier star’s shoes there rather than in the U.S. When Slatkoff was in Beijing recently, she saw five billboards with Bryant’s likeness near the Olympic stadium site to promote his new shoe line.

Aside from jumping into new markets in order to succeed, athlete lines must stand out with their advertising campaigns. “Building a character around someone is effective, like Nike and LeBron James,” Slatkoff said. “Creating a story around athletes and their shoes can make a mark.”

The problem is, all that hard work can disappear in a snap with just one error in judgment. Just ask Michael Vick.

Last, but not least …

Just as sports apparel executives have no power over bad news coming out about their highly compensated athletes, sports TV pooh-bahs can pay tens of millions for rights to air games and not even control what they’ll be showing.

Take TBS’ inaugural venture into baseball’s postseason. The five series they broadcast could have gone as many as 27 games. Instead, the division series and the National League Championship Series ended in 17 games, one over the minimum possible. The two dream teams in big National League markets Chicago and Philadelphia fizzled early, leaving a Colorado-Arizona matchup that lacked appeal east of the Mississippi.

Fox must have grimaced at the thought of a Cleveland-Colorado World Series, which would have possessed little star power to draw the country at large. Now, the storyline is one of baseball’s most classic teams brimming with stars, the Boston Red Sox, against the upstart, white-hot Colorado Rockies. A good matchup that should captivate most of the United States, especially if it reaches a seventh game.

It’s gotta be the shoes ... and the reputation

Apparel sales made up about $50 billion, or 44 percent, of the global sports market last year, and they are on the rise, jumping 8 percent in 2006 in the United States alone. So why do companies continue to base product lines on the reputation of pro players? SportsBiz Spotlight, by MSNBC.com contributor David Sweet.