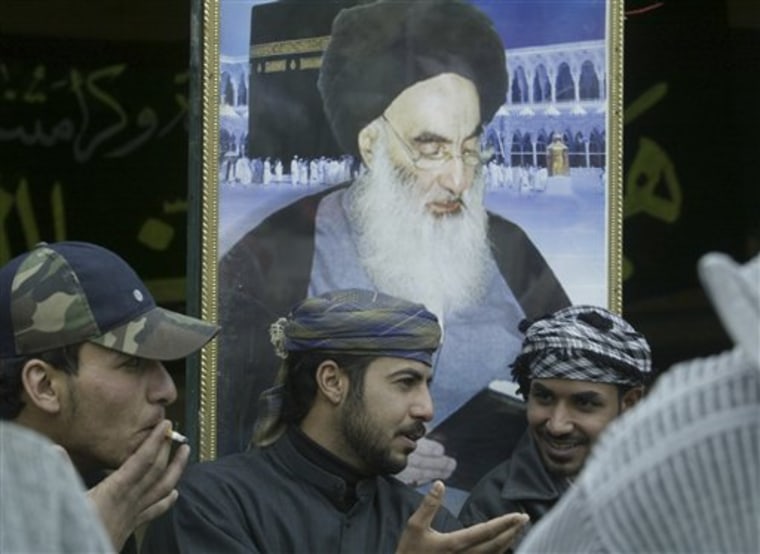

Iraq's most influential Shiite cleric, Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, has sharply reduced his workload in recent months, raising new questions about the health of the aged leader and the prospect of a dangerous power vacuum without a clear and dominant successor.

Any change in al-Sistani's role or reach could have far-reaching consequences for both Iraq and the United States, which consider the Iranian-born cleric as perhaps the most powerful figure in Iraq and a vital stabilizing force in the oil-rich Shiite heartlands of southern Iraq.

The most worrisome scenario is that — as al-Sistani's vast clout possibly wanes — the majority Shiites could further splinter into factions that could rattle Iraq's Shiite-led government and boost militias openly hostile to Washington.

Such an upheaval also would strike a direct blow to U.S. goals in the coming year: shoring up the government and its security forces while trying to consolidate military gains against Sunni insurgents led by al-Qaida in Iraq.

Al-Sistani — whose exact age is not known, but who is believed to be 79 or 80 — has not been seen in public since a brief appearance in August 2004, shortly after returning from medical treatment in London for an unspecified heart condition. But even behind the scenes, his mix of religious authority and political sway make him more powerful than any elected leader in Iraq, including the president and his prime minister.

Cleric gives son his duties

Recently, however, al-Sistani has noticeably lightened his schedule, according to a range of officials.

They include well-connected clerics, lawmakers and employees at al-Sistani's office. They all spoke on condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity of the subject.

They also cautioned against interpreting their comments to mean that al-Sistani is seriously ill or incapacitated, stressing he has slowed down considerably due to his age and heart condition.

But their accounts offer a portrait of al-Sistani in his twilight. They said al-Sistani — who does not grant media interviews — has turned over many duties and decisions to his son, Mohammed Redha, who also is his most trusted aide.

The cleric has stopped teaching seminary students and has restricted his political meetings to a small and select group of mostly Shiite clerics involved in politics, they said.

Al-Sistani's imprints on Iraq

Al-Sistani now spends much of his day in a residence adjacent to his modest, two-story headquarters on a small alley in the old quarter of Najaf, about 100 miles south of Baghdad and the foremost center of religious study for the world's Shiite Muslims — who make up the majority in Iraq and neighboring Iran.

Al-Sistani does not project the charisma or bluster of other Shiite leaders — most notably Mahdi Army militia leader Muqtada al-Sadr — who rose to prominence after the fall of Saddam Hussein in 2003. But al-Sistani's stamp is on nearly every pivotal decision since the U.S.-led invasion, even though he refuses to meet directly with American envoys.

He forced changes to key political blueprints for Iraq, such as insisting that Iraq's first parliament be directly elected, rather than assembled through a caucus system proposed by Washington. He prevailed again when he demanded that only elected legislators draft the country's constitution — effectively sidelining Sunnis who boycotted elections.

Al-Sistani also is viewed as an important buffer against clerics with known anti-U.S. sentiments, such as al-Sadr, and has encouraged Shiites to support the U.S.-allied government. In 2004, al-Sistani helped negotiate an end to fierce battles in Najaf between the U.S. military and al-Sadr's Mahdi militia.

Al-Sistani has one more key appeal for Washington: his ideological break with Iran's ruling clergy, which he sees as monopolizing the political voice at the expense of secular politicians. The United States has accused Iran of using Shiite militias in Iraq as proxy fighters.

In return for his support, Shiite politicians consult him before announcing new policies and seek his counsel on major issues. The practice gives al-Sistani the unique role of godfather and guarantor to the Shiite-led leadership.

Al-Sistani, who moved to Iraq more than 50 years ago after studying in Iran, is one of four grand ayatollahs in Najaf, but clearly retains the most prestige and standing among his peers.

Yet it's precisely this rare blend of political and religious gravitas that makes him a potential liability. He is a virtually impossible act to follow, leaving open the possibility of a confusing and potentially messy fallout after his death.

For the moment, there is no obvious successor. The three other grand ayatollahs — Mohammed Said al-Hakim, Mohammed Bashir al-Najafi and Mohammed Isaac al-Fayadh — have limited followings and are seen as lacking political wiles.

This is likely to leave a host of religious authorities after al-Sistani, but with none towering over the rest.

"This plurality may not be catastrophic, but it will impact politically," said Vali Nasr, a U.S.-based expert on Shiite affairs.

The biggest rewards could land with two opposing Shiite leaders: al-Sadr and al-Sistani's son, who has ambition to climb the clerical ladder.

Al-Sadr, who leads the feared Mahdi Army militia and has 30 followers in the 275-seat parliament, has returned to seminary studies to attain the rank of ayatollah, his aides say. It's viewed as a step toward declaring himself a "marjaa," or a religious authority — with a radical orientation.

Son seeks to bolster own credentials

Al-Sadr makes no secret of his contempt for a religious establishment in Najaf he sees to be too traditional and co-opted by the country's Shiite elite.

Al-Sadr also has married into one of the most respected Shiite families. His wife's late father, Grand Ayatollah Mohammed Baqir al-Sadr, was tortured to death in 1980 by Saddam's agents.

Al-Sistani's son is also seeking to bolster his own credentials.

Mohammed Redha, in his mid-40s, is teaching advanced religious studies at Najaf's ancient al-Hindi mosque, the officials said. He was born in Iraq and, unlike his father, speaks Arabic without an outsider's accent. Years of serving as his father's gatekeeper and confidante have given him invaluable experience in a religious establishment where the ability to raise money is a close second to theological knowledge.

A brewing rivalry between al-Sadr and al-Sistani's son would be just the latest chapter in a history of bad blood.

Al-Sadr's father was a marjaa and was sharply at odds with al-Sistani before he was killed by suspected Saddam agents in 1999 along with two of his sons. Al-Sadr, who is in his early 30s, enjoys the following of impoverished young Shiites attracted to his Arab ancestry and anti-American zeal.