Why does Australia's lonely red heart keep bringing me back like a dog to an old shoe?

Here we go again, loading the cooler with provisions in a supermarket parking lot in the spent-out mining town of Broken Hill. Excitement reigns: Good-bye life as we know it! We are heading out — the landscape photographers Len Jenshel and Diane Cook, the Aussie guide Mike Keighley, and I — on a four-wheel-drive adventure to that parallel universe known as the Outback, and we're stocking up because once the pavement runs out, the only lunch spot we're going to find is some dry riverbed.

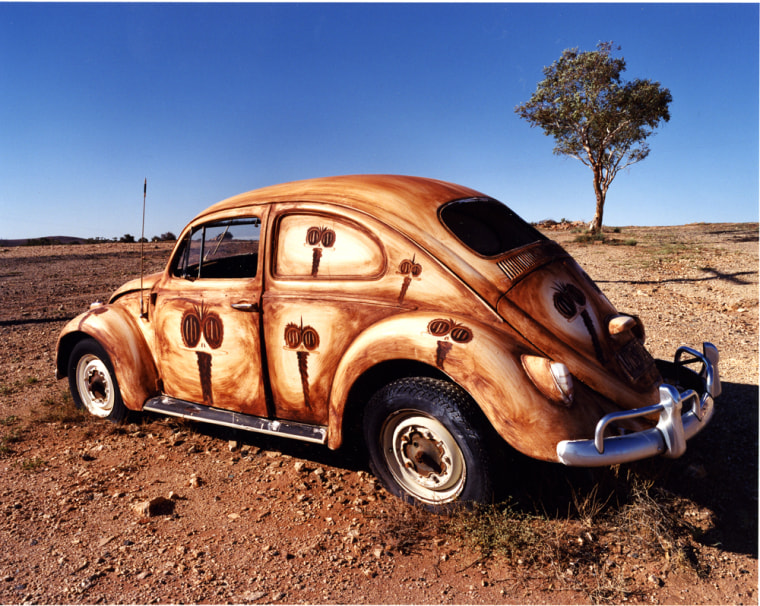

We linger in the ghost town of Silverton, the end-of-the-world backdrop for Mel Gibson's “Road Warrior” heroics. The old sandstone buildings, crumbling gracefully under the merciless blue sky, are now inhabited by artists who like to paint tripped-out emus on junked Volkswagens. But even such batty license (it's par for the course in the Outback) can't keep us from hitting the road. And soon enough we're watching real emus strut their stuff — prancing ahead as if to taunt us, then hustling away, waggling their big feathered butts.

We modern, sensitized, pre-apocalyptic road warriors are driven not by any Mad Maxian fury but by a frolicsome cross-cultural curiosity. We are out to make contact with those odd-duck Australians who've been suckered away from the lush coastal plains to serve out their sentences on the driest, flattest, least populated hellscape on earth. My rule of thumb? The bleaker the stage, the bolder the characters.

The Outback covers practically all of Australia. Imagine a waste area, a sand trap, stretching from Scranton to San Bernadino. After three previous crossings, though, I know that it's far from a featureless void. Along the dirt road to Tibooburra, the land is hillocked at first and speckled by mint-green saltbush, with the Flinders Ranges wrinkling the horizon. Later, witchy-fingered trees appear in the desert's creases, with gums standing taller in the sandy creek beds. A system of fair-weather clouds trundles across the sky. Then the land turns naked and stony.

Wherever you look, no one is home. Tire tracks lead away to an unseen cattle station, a castaway fridge serving as the mailbox. There is nothing that resembles a fence line. Every hour or so, we make out the dust plume of another car approaching. Ten minutes later we pass it, and Mike, at the wheel, lifts one finger in greeting.

It's 100 degrees, the first day of autumn, when we pull over for lunch. Like the jolly swagman in “Waltzing Matilda,” we settle under the shade of a coolibah tree, and our guide tells the story behind Australia's melancholy anthem. The swagman is a heartbroken traveling handyman who is hunted down for killing a landowner's goat and drowns rather than surrender to the authorities. “It's about our underdog mentality,” Mike reckons. “It goes back to our convict days.” So that Aussie swagger is a smoke screen? “We have a tall-poppy syndrome,” he says. “Achievers get cut down to size. When Russell Crowe comes home, he goes back to the pubs. ‘I'm one of you!’ he's telling them.”

Scratch an Aussie: He'll take the simple pleasures. Our picnic table is a slab of tree bark. A wedge-tailed eagle provides the air show. Mike banters, “Who's got the Vegemite?” A kangaroo spies on us, then bounds away.

Planet Australia. We've just begun this journey and yet already we have arrived, like moths to the flame.

The trip started in high style. We three Americans flew into Adelaide and drove up through the Clare Valley to a 106-year-old pastoral homestead, North Bundaleer. What a fine refuge after a long flight — a gabled, nine-chimneyed, iron-roofed manor house on 400 acres of bush at the Outback's edge. A stained-glass foyer leads to a ballroom with hand-painted-relief wallpaper and a grand piano. The dining room has an Irish Georgian table where the hosts eat with their guests. The library has Kipling and Byron under glass, with a Jack Russell dozing in the late-day sun.

The benevolent, bushy-browed owner, Malcolm Booth, suggested, “We can ruck up for drinks anytime we want.” Forthwith he poured a Clare Valley cabernet malbec from the open bar, and we ambled out to the veranda. He told us the innkeeper's tale: how he and his wife, Marianne, were management consultants looking to escape from Sydney when they found this relic eight years ago, deserted by all but the birds and the sheep. As he detailed the renovation, we watched parrots chasing from treetop to treetop while the sun set over his fragrant estate. Here was one dream fully satisfied — for Malcolm and, so briefly, for all of us.

The next day we took our last paved highway — to Broken Hill, where we enjoyed one more night of high-end lodging at the Royal Exchange, a restored Art Deco hotel. Broken Hill sports a few majestic buildings from its 19th-century silver-rush days and is otherwise a plain-Jane country town, the sidewalks canopied against the sun, the streets named Beryl and Cobalt, Sulphide and Chloride. After the mining went bust, artists started moving here for the good light and the simple housing. Now a refigured Broken Hill boasts 34 galleries and an international sculpture park.

We were smitten by the folk art that distinguishes a cheap hotel called Mario's Palace. Italian immigrant Mario Celotto bought the place in 1973 and, lying on scaffolding and copying from a postcard, painted Botticelli's “Birth of Venus” on the two-story lobby ceiling. An Aboriginal mate of Mario's later covered every wall of the sprawling barroom with murals of an Outback that gushed with mighty rivers, lakes, and waterfalls — a vision of the inland sea Australians have always fantasized about. Mario's son Marat, who now runs the hotel, showed us around, recalling why the place looked so familiar. It was a prime location for “The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert.”

A law of the Outback: Eccentrics attract.

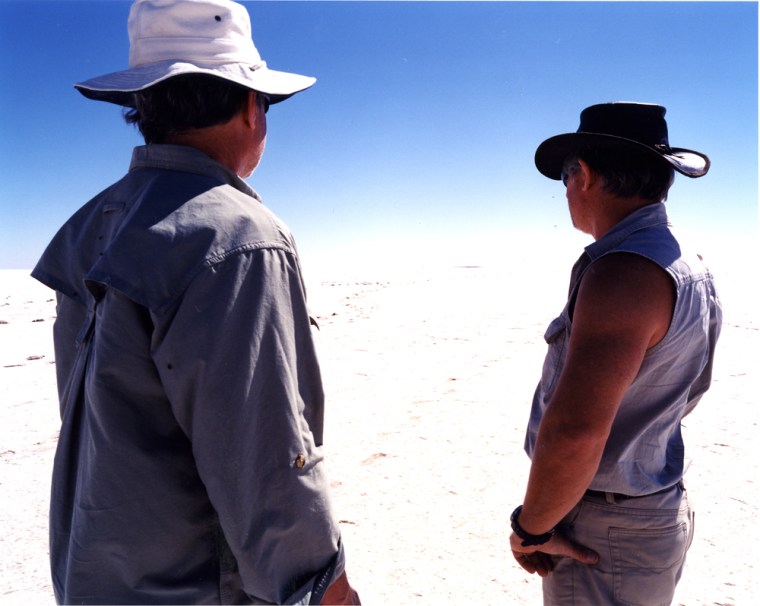

On the road to Tibooburra, the winds are kicking up dust devils. Willy-willies, the Aussies call them. If they're “knock-'em-down winds” from the south, Mike says, they could bring rain and relieve Australia's interminable drought. He turns the Land Rover around to look at a salt pan, and we get out. Standing comically small and alone, engulfed by the sky, we hear only one earthly sound: the GPS cooing insistently, “Perform a U-turn when possible.”

Tibooburra, like most of these Outback settlements, came to life in the late 1800s, when Australia was flexing its nationhood, and miners and ranchers were probing the interior. Today, its landmarks are two small grocery stores with gas pumps, the Werks 'n' Jerks hardware store, the Corner Drive-In movie with eight rusty chairs upended poetically around two headless speaker posts, a pub referred to as the Two-Story Hotel because it's the only such architectural marvel around, and the 1883 Family Hotel, where we're staying. A park features a large overturned boat — an artist's take on Charles Sturt's 1845 expedition to find the inland sea, a search that ended near here and was 130 million years late.

We walk under some rare shade trees and into the Family Hotel's front bar. “When's happy hour?”

“Every hour on the hour,” assures the publican, Pete. He recommends the Coopers Pale Ale. “It's real beer,” he says, rolling it along the bar to stir up the sediment.

I feel at home because Pete Petrovich reminds me — the smoker's rasp, the beer belly, the thinning hair — of my favorite uncle, the one who had a bar in his basement. I take a stool next to a rangy leatherneck who's wearing the biggest, baddest cowboy hat I've ever seen. I introduce myself, my pen poised to record his rugged wisdom. But his ’Strylian twang is so boinky I can't make out a word.

Pete tells us our rooms are across the road. “You've got satellite TV but just one channel. Whatever I decide to watch in here is what you're watching in the rooms.”

The curly-haired barmaid, Karen, asks me, “How would you like to see some Tibooburra gold?” Her husband is a prospector. I'm playing journalist: “How many people live here?” “A hundred,” she says. “When everybody's at home.”

The Family Hotel is known for its outrageous murals, which seem to be an Outback specialty resulting from the excesses of solitude and time. Stretching across two walls of the bar is a bacchanalian romp painted in 1970 by the Melbourne portrait and landscape artist Clifton Pugh. He added some personal touches: a devil who looked like his ex-wife's boyfriend, and two nudes who turned out to be the pub owner's daughters. Other fanciful murals by recognized artists grace the hotel's back rooms, all painted for free, or leastwise for beer. A Sydney disc jockey came out here recently and declared one mural worth a million dollars. Pete laughs. “I told him I'd throw in the pub for that.”

Pete slides a couple of polished pebbles across the bar: Tibooburra gold. After 12 years, he says, he's ready to sell the pub and re-up for civilization. When he came here, he had a wife — “a city-born gal” — but she's gone. A barkeep in Broken Hill suggested, “She done too many good dances on the bar.” Pete, instead, is reflective: “It was more the pub than the isolation, working together every day. You can spend too much time with someone you love.”

After dark, at a table outside, we travelers work through some ornery rib eye steaks, a warm breeze playing restless with the trees. Later I check out the Two-Story Hotel. It's a Friday night, the backbeat coming from a car parked outside. I get ensnared by some locals who are buying Tibooburra Shooters. A big woman flings her arms around my neck, and I look for the door. When she turns to put a headlock on a guy with a Mohawk, I duck out. That's when I realize: It's raining.

It rains all night, mates, and in the morning the road signs at both ends of town announce that every way out of here is closed. We are pining to drive up to Innamincka (with its Outamincka Bar), then to the legendary Birdsville Hotel, and down the Birdsville Track to Mungarannie. But the routes up north, we're told, will be flooded for days. If we get caught trying, the fine could be $1,000 a wheel. Mike and I drive out of town for a few miles, cautiously. A truck comes by with its whole front end ripped off — the bumper, the grille. Mike murmurs, “He went into a washout too fast.”

Back in my ’50s-style motel room, I flip on the TV — an infomercial for a workout machine. Why is Pete watching that crap? I walk across the road and ask him if we can keep our rooms. He points out that nobody could get here to claim them. “You can't leave tonight anyway,” he says, “because we're havin' pea-and-ham soup. I make it myself!”

And what a cozy night it ends up being, for at the Family Hotel we are already regulars. Skinny Karen greets me with a Coopers: “There you go, darlin’.” I say hello to Tony, the guy from Victoria who's considering buying the hotel; to Wayne and Steven, the gas-field workers we met out scouting the roads; to Alex, the Mohawk in the headlock last night, who teaches for the Outback School of the Air; to Kate, the Two-Story's bartender; to Robert, the pipeline repairman who looks like a wrestler; to the cowboy whose palaver I cannot comprehend; to the grizzled mute who sits alone; and to Uncle Pete, who was right about the pea soup.

Outside, the sky is all stars again. A guitar appears and we sing: old American folk rock, mostly. Way out here, they know all the words. We also sing “Waltzing Matilda” and “A Bushman Can't Survive on City Lights,” and now I'm getting sentimental. I'm so lucky we had to stay another night in Tibooburra. This fellowship of outcasts, this instant community, this fleeting camaraderie in the dead center of nowhere, is what I came here hungering for.

Next morning we watch a worker in a black cowboy hat flip the giant road sign from closed to open. “An Outback traffic light,” Mike muses. “It changes every two days.”

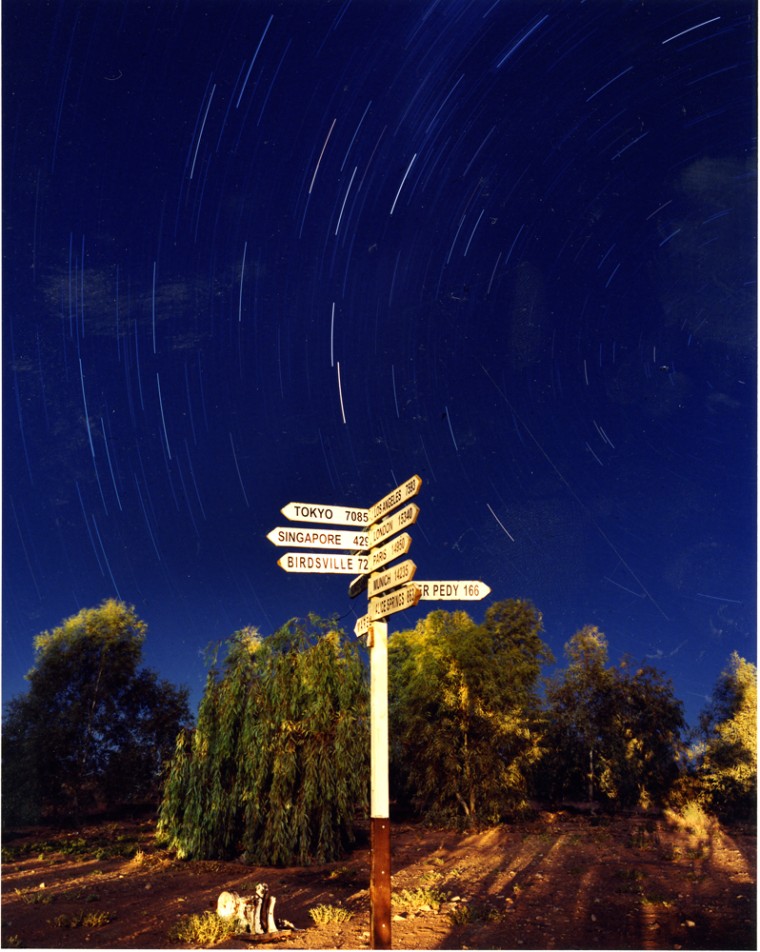

Cameron Corner is located where three of Australia's six mainland states — South Australia, New South Wales, and Queensland — come together. Also in play is the Wild Dog Fence, which is meant to keep dingoes away from sheep and which crosses Australia, incredibly, for 3,500 miles. So in his spare time (which must be most of the time), Bill has laid out a unique nine-hole, par-three course: “There's three holes in each state. You have to shoot over the dog fence twice, and over the national park fence once.”

Bill and his missus, Chris, who moved here a year ago to double the population, sit with us. I ask, looking out the window again, “Do you landscape the fairways?”

“It's just as it is,” he says, like some toothless guru. He adds that the “browns fee” includes clubs, balls, and bottled beer (buried in a cooler at hole five).

I challenge the club pro to a one-hole match, and we make like it's the Masters. But Bill is a clown, a one-man riot — stomping on my ball, whacking the flagstick with his eight-iron when he misses a “putt.” The cup is the cap end of a gas-field drill head, the pin a length of PVC. He wins the match and gives me a ball imprinted with the promise of more tomfoolery to come: the Three-State Open.

Then off we go into the wild beige yonder, driving across sand hills that give us roller-coaster rides and out onto the flatlands again, without a pretense of vegetation. As in a dream, we come upon the bullet-holed skeleton of a London double-decker bus squatting beneath the withered arms of an abandoned windmill. There are no further clues, so we drive on, searching for a rumored shortcut marked by a car door. There's no one to ask for directions except two roos up on their hind legs, duking it out. We drive through boulder fields, beside white dunes tufted with shrubs, across a gibber plain of polished stones, past the haggard humps of Mount Hopeless.

What is there to see out here? No one dares to sleep.

It is sunset (oh, the photographers are happy) when we arrive at the outpost of Marree, which began in the 1870s as a staging area for Afghan camel handlers. We check in to the imposing Marree Hotel, made of cut sandstone like many of the pubs, and the walls inside are hung with antique camel-driving gear. As it happens, one-third of Marree's fourscore residents are descendants of those cameleers, and another third are Aboriginal. It is our twisted luck, however, to eat dinner with Bob Backway.

A retiree with a gray ponytail, Bob is the commodore of the Lake Eyre Yacht Club. It says so on his business card, and that would be impressive if there were, in fact, a Lake Eyre. Bob's enduring passion is to sail his 14-foot catamaran on what he boasts is the world's eleventh largest lake. Yet such sport is possible only when the lake has water, which is next to never. On average, every eight years. And even then, the hundred-mile-long lake is but three feet deep. “You have only a few inches’ clearance,” he confides. “You just don’t” — he demonstrates — “jump up and down.”

At least it's a safe sport, we allow. But Bob says the water’s no good. “It's heavy, like baby oil. There are no waves at all. The salt leaches the oil out of your fingernails, splits your thumbs, gives you onion toes.” While I try to savor my kangaroo steak in plum sauce, he hoists a bare foot to show how his big toe is peeling away.

Commodore Backway says his hero is the explorer Charles Sturt, who first yearned to navigate the inland sea. I try to imagine being Bob — tacking through knee-deep goop in 120-degree heat, with dingoes howling from the brackish shore. I venture, “You must be pretty much alone out there.”

“That's why I like it,” he says. “I hate crowds.”

The Outback: one boundless playground for the random mutations of the undisciplined imagination. In the morning, driving up the Oodnadatta Track to William Creek, we come to another breathtaking intersection of empty space and the artistic impulse. It's somebody's homemade sculpture park, featuring two vintage airplanes standing on their tails in the bare desert with their wings overlapping like brothers in arms. Planehenge, it is labeled: “Conceived and raised by Mutoid Waste Co. & Friends to mark the passing of the Earth Dream Journey.” Beyond Planehenge are a water tank turned into a colossal dog and a bus reborn as, what, a spaceship?

At day's end, a hundred miles from any other settlement, is William Creek: namely a pub, a store, an outdoor museum, an airfield, another invisible golf course, and nine residents — although a tenth is coming home tomorrow. The local humor is such that the iron-sided William Creek Hotel (1887) has a parking meter out front. The pub is famous for its hectic interior decor, and indeed every inch of wall and ceiling is covered with past drinkers' shirts, shorts, hats, shoes, bras, and underpants, all duly signed by their donors, along with license plates, photos, drawings, tea towels, flags, foreign currency, and police patches. The trusty pool table, too, is all ascribble with signatures, epithets, Web addresses, and knife cuts. Len and Mike and I shoot a game, then ink in our sentiments. A retired cattle dog named Jed patrols the pub, very slowly. His bed in the corner specifies DOG ONLY.

The hotel has just one room available tonight, so Mike and I jump at the chance to sleep outside. Since we'll be taking a scenic flight early in the morning, we ask pilot Trevor Wright at the pub if we can sleep on his runway.

“Sure,” he says. “Sleep wherever you want.”

“This way,” Mike reckons, “we won't miss our flight.”

Trevor nods. “You'd be the first to know.”

Thus we have the privilege of unrolling our swags under a wide-open midnight and, with a runway marker for a pillow, going to sleep under a sky so undimmed by artificial light that the stars fairly kiss the horizon. Every time I open my eyes, the Southern Cross has wheeled farther through the sky, from our last adventure to the one ahead, and when the sun comes up, the Cessna is ready to go.

Planet Australia. From 500 feet up, I look for William Creek, but it has vanished into the leopard-spotted bush.

Once more the rains come down at night to slicken the clay pans, flood the washes, and close the roads. We almost get stranded again, in Oodnadatta, before making it out to the pavement at Coober Pedy. But this larger town, thank God, offers no respite from the prevailing weirdness. Its better homes and tourist rooms are burrowed into hillside caves to escape the heat. I recline in my pricey cocoon, contemplating walls and ceilings massively toothmarked by tunneling machines yet fantastically swirled with the molten browns and golds of inner earth. Coober Pedy: a fitting name. It's Aboriginal for White Man in a Hole.

Most of the world's opals are dug up here. The town is surrounded by myriad slag heaps poking up from make-or-break mining claims like so many prairie dog mounds. The miners are mainly immigrants, in 49 different flavors (make that 48; the Inuit just left). Look at the names in the cemetery: Szabo, Vekic, Stojan, Dracopoulos, Giacomelli, Kazikoff. Karl Bratz's headstone is a beer keg inscribed HAVE A DRINK ON ME. Crocodile Harry's bones are marked with three bottles of Coopers.

Steven Eger, who came over from Hungary in the 1960s, shows us his opal jewelry for sale and his mining rig — a seat dangling from a winch over a hole 70 feet deep. I peer in: “Do you find much down there?” He bristles. “You from the KGB?” Around his yard are scrap sculptures he has fashioned from computer monitors, mannequins, vacuum cleaner hoses, and wheelchairs. He points out a donation box: “Don't put in anything I can hear hit the bottom.”

The miners have their social clubs — the Italian Club, the Serbian Club, the Croatian Club — but after a day of digging they all come together, brothers in exile, at the Opal Inn's pub. Here, standing at the bar, I am approached by a stout man in a cardigan, Milan by name, who reveals a case holding three low-quality aquamarine opals.

“Twenty dollars for all,” he offers, Slavically.

“Where are you from?” I ask.

“Slovenia!” he proclaims. Then he shouts it for everyone to hear: “DEMOCRATIC SLOVENIA!”

I show the opals to the two Italians and two Croats down the bar. Adriano, a Venetian with a mustache twirled up in circles, appraises them: “Good! Color everywhere!”

I buy the opals from Milan and get Adriano a beer, and he tells me how it was when he first came to Coober Pedy, 30 years ago. “Plenty of opal. Plenty of drinking. Money. Love. Everything!”

I hazard to ask, “How is it now?”

“I don't do any good,” Adriano admits, “but I still try.” He rhapsodizes, “Your America, it is a free country. Frank Sinatra, he sing, ‘I did it my way.’ For me, it is just the same. I have no such luck,” he assures me, “but I did it my way!”

That could be the theme song for everyone we’ve met.

We drive the final leg north to the Outback's capital of Alice Springs. Rainwater has pooled in the roadside gullies but still nothing you could ever hope to sail a boat on.

“Oh, Mama, can this really be the end ...?”

On the outskirts of Alice we run into traffic. Rush hour in the Outback. For the first time in a week we have stoplights to obey. We gawk at a KFC, a Subway, a three-story parking lot — wonders we'd forgotten all about.

Our plan is to celebrate our return by living it up at the Alice Springs Resort, with its palm-fringed pool and swim-up bar. I score a deluxe room, and it's unnecessarily spacious, with a party-size balcony overlooking the Todd River. I even have a television that lets me change channels. So why aren't we celebrating yet? Is it just that the weather's too cool to go swimming?

Our guide, Mike, isn't one to dally in posh hotels. That underdog mentality, I guess. Len and Diane and I say good-bye to him. Then, suddenly feeling incomplete, we walk Alice's downtown mall, past the many shops selling Aboriginal art, didgeridoos, adventure wear, and Outback tours. At a smart bush-tucker restaurant, we dine on camel porterhouse and smoked emu sausage. Is it just the indifferent service and disappointing food, or what?

We'll have to be patient. Until we get reacclimated, until we get re-homogenized and rebooted, this fancier world can't measure up to being stuck in Tibooburra.