If there is a place where heaven and hell meet, it's here.

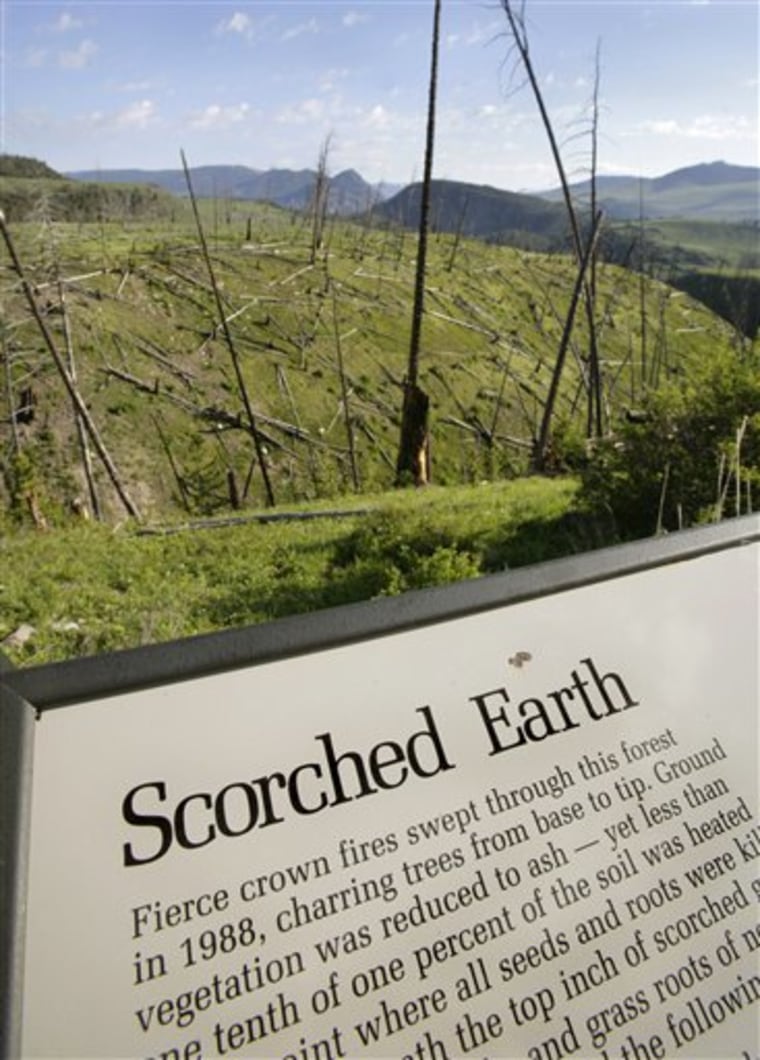

Twenty years ago this summer, a series of wildfires burned 36 percent of America's first national park, scorching huge swaths of pristine forest and killing scores of wild animals. Today, there is new life at Yellowstone National Park, as trees have taken root among the burnt logs that still litter the earth.

The 1988 wildfires were not the ecological disaster many feared at the time. Far from destroying the park, the fires brought new life, cleared out the forest canopies and allowed new plants to bloom.

The fires also, however, forced federal officials to tighten a policy allowing some fires to burn and develop new strategies to battle the "mega-fires" of today across the West.

"The philosophy was, in these large natural areas, fire should be allowed to play its role," said Dick Bahr, a fire science and ecology specialist for the National Park Service. "What happened in '88 in Yellowstone was probably a passing of the threshold with what the political and social world was comfortable with. It was perceived that we were burning up their national park and there would be nothing left of it."

Strategy changed in 1972

For nearly a century, Yellowstone managers were quick to douse wildfires. That changed in 1972, when ecologists, citing years of research, persuaded the park to adopt a policy allowing lightning-sparked fires to burn as long as they didn't threaten lives or park facilities. They maintained fire was a natural event that promoted healthy forests.

In 1988, the fire dangers were not immediately clear. Park officials did not know it would be Yellowstone's driest summer in recorded history, or that the lightning-sparked fires of May would burn into June. More storms in July would bring little rain and more lightning.

"Every single day you couldn't believe that you'd wake up and there was more fire, new fires started," said Joan Anzelmo, the park's spokeswoman in 1988 and now superintendent of Colorado National Monument.

The escalating fire scene catapulted Yellowstone to the forefront of the nation's attention in late July. That's when one of the season's most destructive fires forced the evacuation of about 4,000 people from Grant Village, a collection of lodges, restaurants and a visitor center.

Hundreds of reporters descended on the park. Over the next six weeks, the fires made national headlines as they continued into August and early September. More than 25,000 firefighters battled the fires, costing some $120 million.

On Aug. 20, known as Black Saturday, winds up to 80 mph fanned flames and the fires doubled in size to 750 square miles. On Sept. 7, the park evacuated the historic Old Faithful Inn, which was spared largely due to sprinklers installed on the roof the previous year.

Four days later, the first rain came. By Oct. 17, the fires were contained.

Overall, the fires burned 1,875 square miles in and around the park and destroyed 67 structures in Yellowstone, causing more than $3 million in property damage. Two firefighters were killed while working outside the park's boundary.

Facing criticism over the so-called "let it burn" policy, federal officials put a temporary freeze on allowing fires to burn in national parks. Three congressional hearings were held to review fire management practices for Yellowstone and other public lands.

Park officials say there was never a "let it burn" policy and that they carefully considered each time they chose to allow a lightning-sparked fire to burn.

"Because people didn't understand it — we didn't do a good enough job explaining it back then — it became known as the 'let it burn' policy," Anzelmo said.

In 1992, Yellowstone adopted a stricter fire plan that set limits on where and how big natural fires will be allowed to burn.

"We learned a lot in 1988 about how much fire a park could take before they ran out of resources," said Tom Nichols, the National Park Service's acting chief of fire and aviation.

The 1988 fire season foreshadowed challenges that firefighters have faced over the last decade in dealing with increasingly bigger and widespread wildfires, while at the same time recognizing the good that fires can do for forest health.

For the most part, the number of acres burned each year has been on an upward climb since 1988, from about 5 million that year to 9 million in 2007, according to the National Interagency Fire Center.

Wildfire experts say the reasons for larger fires are numerous and include an over-accumulation of old trees and underbrush resulting from drought, past policies of suppressing fires and insect infestations.

Scientists quickly recognized the ecological value of the 1988 Yellowstone fires, said Norm Christensen, a fire ecologist at Duke University who chaired a panel of independent scientists formed that year to study the consequences of the fire.

"I think the overriding message of our report was, as big as these fires were and as important as they were in many ways, they were not historically unprecedented, and it was not unnatural," Christensen said. "We very emphatically said, and I think the 20 years since then have confirmed, that the fires were not an ecological disaster."

A visit today proves the fires did not destroy Yellowstone National Park.

"You look around, there's wildlife, there's birds, everything's fine," said park visitor Tracey Florio, of Cape Coral, Fla., who traveled to Yellowstone this summer. "Actually, it's a lot greener now. Hopefully, we learned from that. It's OK to let nature do what it needs to do — clean house."