Water locked underneath icecaps or glaciers can tell us about our planet's past and its possibly warmer future. Similar environments on distant worlds could tell us whether life can originate in these harsh conditions. To study the icy depths, a Swedish team of researchers is designing a tiny submersible that can slip down a narrow borehole.

There exists a menagerie of different remotely operated underwater vehicles (ROVs), some of which have already studied the frigid boundaries between ice and sea. However, none of them are compact enough to snake their way several kilometers below the ice.

"Most of the other ROVs are not this small because they don't need to be," said Jonas Jonsson of the Angstrom Space Technology Centre (ASTC) at Uppsala University in Sweden.

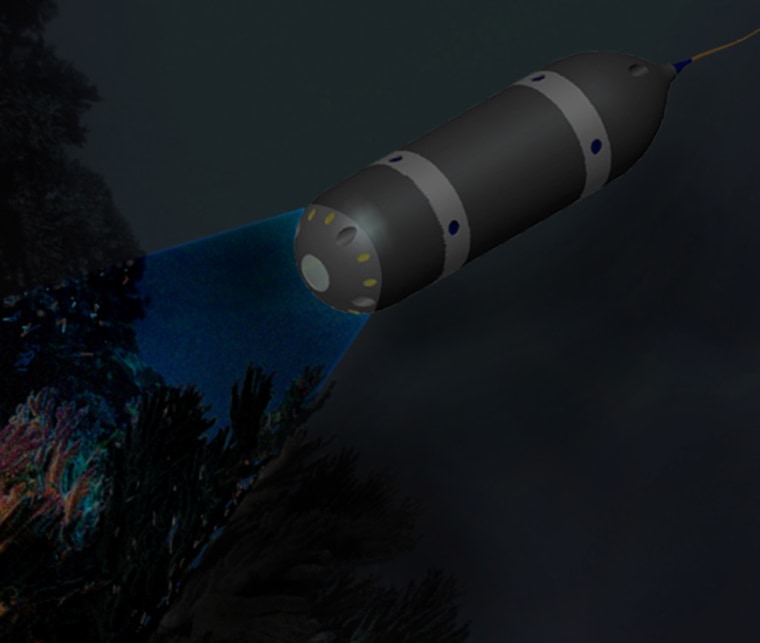

In response to growing interest in studying sub-glacial lakes on Earth, Jonsson and his colleagues are developing a cylindrical probe 5 centimeters across and 20 centimeters long — smaller than two soda cans stuck end to end.

The original idea for a miniature submersible came out of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, Calif. The mini sub was part of a potential mission to Jupiter's moon Europa, in which an ice probe would drill through the moon's thick ice shell and release the sub to explore the ocean thought to be dwelling underneath.

Jonsson and his colleagues are further developing this idea, but applying it to a more immediate goal: studying sub-glacial lakes on Earth. Scientists believe these isolated pools of water may have trapped life forms from possibly millions of years ago.

The small submersible that ASTC is designing could easily be carried by hand on a helicopter or snowmobile and dropped down a previously drilled borehole. It could also be launched off the edge of an ice shelf to study the impact of global warming on the interaction between ocean and ice.

With funding from the Mistra Foundation, which supports environmental research in Sweden, the team is now close to finishing a prototype with propellers and a camera. They plan to begin testing it in a laboratory tank in the coming months.

Miniaturization

As development progresses, the team plans to add micro-electromechanical sensors and a fiber optic interface, as well as prepare it for the high underwater pressures it will likely encounter.

One way to handle these pressures is to build a very strong hull, but that could wind up being too heavy. Another possibility is to use a lighter hull and place a bladder in the center filled with an incompressible fluid that would support it from the inside.

For instrumentation, the researchers have already built a miniature sonar, and detectors for conductivity, temperature and depth are being planned. The mini-sub will also eventually carry chemical sensors that can detect hydrothermal vents, which may harbor life in otherwise hostile environments, Jonsson said.

To zero in on a vent or other scientific target, the researchers plan to control the submersible (as well as receive data) through a fiber optic cable. The advantage of optic fibers is that they are thinner and more flexible than copper wires. They can also send data at higher rates and over longer distances.

Ultimately, a remotely-controlled submersible could look for signs of life under the icy shell of a distant world.

"This could be a forerunner for technology that could be sent to Europa," Jonsson said.

The design would need to change. For one, Europa's surface is colder (minus 160 degrees Celsius) than anywhere on Earth. And some scientists have suggested that a subsurface ocean on Europa may be highly acidic.

Regardless of what challenges a potential Europa mission may offer, this research may provide one vital lesson.

"We are investigating how small and light a submersible can be built, which could be very important for space travel," Jonsson said.