In a way, Neel Kashkari's job has always been to keep it together.

Today he's known as the 35-year-old whiz kid appointed czar of the Treasury Department's $700 billion financial bailout. But in a past life, he was a young engineer working on the James Webb Space Telescope, planned as the even-more-intricate successor to the iconic Hubble.

Even then, Kashkari's job was about maintaining stability and confidence.

His work for NASA contractor TRW Inc. — helping create a key latch — was meant to keep the telescope from shaking apart in the "mini-earthquakes" it would endure in orbit, said his former supervisor, Scott Texter. Using pioneering techniques, Kashkari rigged up devices in the company's Smart Structures Lab that measured distances to a precision of "an atom or two" and proved that the telescope could remain steady.

"He's a guy who tries to prevent dynamical disturbances, whether they were structural or financial," said Texter, manager of the telescope portion of the project for Northrop Grumman Corp., which acquired the division of TRW that was working on the NASA contract. "I'm not at all surprised that the skills that Neel had ... as an engineer could be well brought to bear. I wish we had more engineers in Congress."

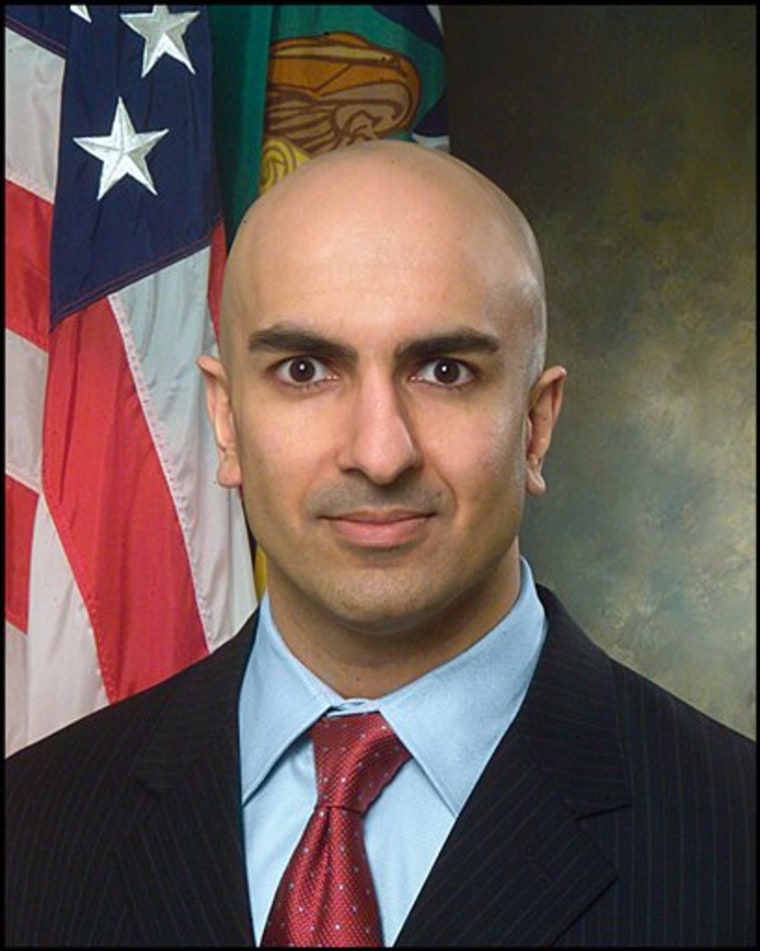

To many Americans, it might seem that the young man with the shaved head, dense, dark eyebrows and intense, brown-eyed stare is coming out of nowhere — or that someone barely six years out of business school may not be equipped to handle a sum comparable to the cost so far of the Iraq War. But he is part of a domestic finance team at Treasury that has been working 18-hour, Diet Coke-fueled days for months behind the scenes on the mortgage and securities crisis, and he would tell people they shouldn't be focused on his relative youth.

"I'd say that at the end of the day, what's most important is to have the trust of the secretary, and the president for that matter," he told The Associated Press in a telephone interview Wednesday. "... let's also not oversell what I'm doing. You know, Secretary (Henry) Paulson is the guy making the ultimate decisions on where we're going to be deploying this and in what form."

Kashkari called his sister on the way home from work Monday evening to tell her about his new assignment, a responsibility that she said he recognizes as an honor to be earned again and again.

"I realize that he's young compared to other people," said the sister, Dr. Meera Kelley. "He realizes what is at stake here. He realizes that the public has put their trust in this project, which is huge, and that he's going to have to proceed very cautiously and effectively in order to keep the public's trust." But she said his dedication and willingness to seek out guidance make her little brother "an excellent point person" for the daunting project.

Neel Kashkari — his first name can be translated as "blue" but is also an ancient Indian mathematical term for the number 10 trillion — was born in Akron, Ohio, and grew up in Stow, south of Cleveland.

His parents, Chaman and Sheila, immigrated from the disputed region of Kashmir in the 1960s for better economic opportunities, their daughter said. Chaman retired from the University of Akron as an engineering professor, and his wife is a pathologist.

As a kid, Neel spent hours building ships, cars and trucks with Lego blocks, Lincoln Logs and Erector sets. He recalls watching the NewsHour with MacNeil/Lehrer, the McLaughlin Report and other politics and talk shows with his dad.

He liked sports (he named his pet Newfoundland dog Winslow after Cleveland Browns star Kellen Winslow, and the avid skier painted his helmet the team colors, orange and brown), but he never showed an interest in making money growing up, his sister said.

"He did not have a lemonade stand or any kind of a little business when he was younger," said Kelley, 42, a physician and hospital administrator in Raleigh, N.C. It was clear by high school that he was going to follow in his father's footsteps.

"Even as a young science student, Neel possessed a synthesizing mind, able to take seemingly disparate bits of information and connect them into a coherent whole," said Patrick Smith, who taught Kashkari biology at Western Reserve Academy in Hudson, Ohio.

Kashkari competed in football and wrestling at Western, and even played the role of head waiter in the school's production of "Hello Dolly." He received departmental honors in mathematics and was chosen by the Class of 1991 to be the graduation speaker.

While attending the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Kashkari led the mechanical engineering portion of the school's entry in the 1997 "Sunrayce" — an event in which teams design and build a solar-powered vehicle, then race each other from Indianapolis to Colorado Springs. The "Photon Torpedo" didn't win, but Kashkari impressed.

"Everybody recognized that he was the one — he was the guy that should be in charge," said fellow student Jonathan Kimball, now an assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering at the Missouri University of Science and Technology in Rolla. "He was always very committed and very driven."

With bachelor's and master's degrees from Illinois — and a future wife, Minal, also an engineer — Kashkari went to work in 1998 for TRW in Redondo Beach, Calif., where he was a principal investigator in research and development.

"He was one of my favorite engineers to work with," remembers Charlie Atkinson, deputy manager for the telescope project. "Very easy going."

Atkinson said Kashkari had "a very good briefing style," which came in handy during the competition phase. He inspired confidence in those who heard him.

"I knew when I would get an answer from Neel that I had 100 percent faith in it," Atkinson said.

Kashkari shaved his head even back then, prompting colleagues to tease that he looked like a character from the Brendan Fraser "Mummy" movies. Watching him tool around in his prized Corvette, it seemed to Texter that Kashkari was "the sort of person who wanted a more high-profile, affluent sort of existence than being what an engineer would generally afford."

So, his co-workers were caught off-guard when Kashkari sold the black sports car and signed up for an MBA course at the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School.

"We never talked about money," said Allen Bronowicki, who shared lab space with Kashkari at TRW's Building R4.

While at Wharton, Kashkari volunteered for a rigorous "leadership venture experience" at the U.S. Army's battle simulation lab at Fort Dix, N.J. The exercise involved a mock cease-fire in Bosnia, and the students were broken up into teams representing NATO, the Red Cross, the Army and other organizations coordinating to get relief to 300 refugees.

Professor Michael Useem ran the exercise and said Kashkari's willingness to put himself through the Army simulation revealed his drive and his abilities to function under "trying and, sometimes, even hostile conditions."

"He's been invested with enormous authority ... at one of the most critical junctures of our generation," said Useem, director of Wharton's Center for Leadership and Change Management, adding that he understood why someone with Kashkari's qualities was chosen.

It was during a summer internship at the investment bank and securities firm Goldman Sachs Group Inc. that Kashkari "really got that passion" for high finance, his sister said. In 2002, he joined Goldman Sachs in San Francisco, where he headed the information technology security investment banking practice.

In February 2006, Kashkari had a meeting in New York with Paulson, then the firm's chairman and chief executive officer, to talk about his interest in public service. When he heard of Paulson's nomination in July, he called him back.

"`Hank,'" he recalled saying. "`Do you remember that conversation we had a few months ago? If you're putting a team together, I want to come with you.'"

A week later, he was being sworn in as a senior adviser responsible for developing the President's Twenty in Ten energy security plan. He has also been involved developing and executing the department's response to the housing crisis, addressing the sub-prime lending debacle and helping to draft the legislation that Congress passed last week creating the $700 billion rescue effort.

Not everyone praises his work. John Taylor, president of the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, has questioned Kashkari's leadership of Treasury's Hope Now Alliance, a government-industry group trying to prevent individual mortgage foreclosures. In an interview with National Public Radio, Taylor faulted making industry participation voluntary and said of Kashkari: "He keeps his cards close to the vest, so it's hard to tell what he's thinking."

But the same confidence and presentation skills that so impressed his colleagues on the telescope project were evident during a presentation Kashkari made last month at the American Enterprise Institute on covered bonds, a kind of mortgage-backed security popular in Europe.

"I'd never heard of the covered bond until a year ago," he admitted to the crowd. "It took me a while to get my head around it."

After one questioner grilled him about why he should feel good about the government getting into "market innovation," Kashkari calmly explained that there "there IS no silver bullet" for any of these ills.

"I'm a free-market Republican," he said, repeatedly clearing a throat scratchy from many late-night sessions. "As much as I would like to believe, 'Just let 'em free and everyone's going to work out their own problems,' we're under a lot of pressure right now. All of us are feeling a lot of pressure."

Kashkari was sworn in as Assistant Secretary of the Treasury for International Economics and Development in July, but his immediate boss, Under Secretary for International Affairs David H. McCormick, has had to share him with Paulson quite a bit as Kashkari has attended to "Job 1 for the Treasury — for the country."

Skepticism of the government's ability to steer us out of this crisis is high — a wag commenting on a Wall Street Journal story jokingly dubbed the new bailout czar Neel "Cashandcarry" — but McCormick cautions anyone thinking Kashkari is too young and too inexperienced to shoulder such a monumental load.

"He's very analytic. He's very fact-based. He's very unemotional," said McCormick, sitting in the office suite from which Andrew Johnson ran the country in the wake of another national crisis — the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. "I don't mean lacking emotion toward the toll these housing market challenges are having on everyday Americans, the impact of the financial market situation on families. ..."

Kashkari said it's not as big a stretch going from aerospace engineering to re-engineering a financial system as people might think.

"As an engineer, what I loved about it is I was solving problems, or we were trying to solve problems that no one had ever even tried before," he said. "When you think about the credit crisis, we're trying to tackle challenges, maybe they've come about in the past in different forms, but the situation today is by definition unique. So we're bringing all of our analytical skills to bear to try to solve this."

Geoff Johnson, who was one of four people on a Wharton "learning team" with Kashkari and has vacationed with him many times since graduation, said his old friend called to tell him about his appointment as interim bailout czar. He said Kashkari is under no illusion that he's doing this by himself.

Johnson, a hedge fund manager, quoted him as saying: "This is still Hank's project. ... I'm just here to make it happen."

Kashkari's father added in an interview with The Akron Beacon Journal: "I am sure God will guide him. He loves this country. He is proud of this country. He feels America is a country that can bring peace and prosperity to the world."