For years, he operated along Syria's remote border where donkeys are the only means of travel. He provided young Arabs from as far away as Morocco and the Persian Gulf with passports, guides and weapons as they slipped into Iraq to wage war.

But recently, the Iraqi man known as Abu Ghadiyah began doing even more — launching his own armed forays into his homeland, U.S. and Iraqi officials say.

Finally the United States lashed out, frustrated it says, after years of vainly pressuring Syria to shut down his network supplying the Sunni insurgency.

The Americans carried out a bold daylight raid Sunday in a dusty farming community of mud and concrete houses known as Abu Kamal, just across the border in Syria. The U.S. says Abu Ghadiyah and several bodyguards were killed. Syria says eight civilians died. At least one villager says U.S. forces seized two men and hauled them away.

Whatever Abu Ghadiyah's fate, the attack targeting him has become a seminal moment — casting rare light on the hidden, complex networks that recruit foreign fighters and then deliver them across Syria to the battlefields of Iraq.

A murky web

Syria has long insisted it monitors the border and does all it can to stop weapons and fighters.

"They know full well that we stand against al-Qaida," Syrian Foreign Minister Walid al-Moallem said Monday in London. "They know full well we are trying to tighten our border with Iraq."

But the raid and U.S. documents — recently made public — indicate that insurgents operating in the Syrian border region are still providing the material that enables suicide attacks, bombings and ambushes to continue inside Iraq.

Even as the insurgency has fallen on rough times — battered and bleeding but not yet defeated — the networks themselves have become more organized, the documents indicate. That raises fears the insurgency could someday arise anew.

The documents also shed light on the murky web of religious extremists, professional smugglers and corrupt Syrian intelligence officials who run the smuggling networks — some of whom view Syria's government in faraway Damascus with contempt.

Until the raid, Abu Ghadiyah, whose real name was Badran Turki al-Mazidih, was mostly unknown outside a tight circle of Western and Iraqi intelligence officers. They tracked his movements, and the al-Qaida commanders who relied on his services, believing him a senior figure in al-Qaida in Iraq.

Abu Ghadiyah housed his recruits both in Damascus and the Syrian port of Latakiya before moving them across the Iraqi border, one senior Iraqi security officer said Tuesday. He spoke on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to talk to media.

Scores of people are involved in the smuggling networks, officials say. But Iraqi police held special disdain for Abu Ghadiyah, a native of the northern Iraqi city of Mosul believed to be in his early 30s.

Last May, Abu Ghadiyah led a dozen gunmen across the border and attacked an Iraqi police station in Qaim, killing 12 policemen, Iraqi police Lt. Col. Falah al-Dulaimi told The Associated Press on Tuesday. Syrian border guards prevented an Iraqi patrol from pursuing the gunmen back into Syria, the police officer said.

Smuggling fighters

Sunday's raid was launched because of intelligence that Abu Ghadiyah was planning another attack inside Iraq, a senior U.S. official told The Associated Press, also speaking anonymously because the information is classified.

Much of the publicly known information about networks such as Abu Ghadiyah's comes from documents seized during a U.S. military raid last year on a suspected al-Qaida hideout in the Iraqi city of Sinjar.

Those documents include records of about 590 foreign volunteers who entered Iraq from Syria, according to the Combating Terrorism Center at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. The center released a report last July based largely on the documents.

According to the documents, nearly 100 Syrian coordinators are involved in transporting foreign fighters through Syria. Some are professional smugglers apparently hired by al-Qaida in purely business deals. Others are motivated by al-Qaida's hardline Islamic ideology.

Abu Ghadiyah's real beliefs are unclear, but a U.S. Treasury document says he was appointed as al-Qaida in Iraq's logistics chief for Syria by the group's founder, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. That suggests Abu Ghadiyah was indeed a true believer.

Coordinators' fees

The coordinators worked with the young Arab volunteers recorded in the Sinjar documents — most of whom came from Saudi Arabia and Libya, with others from as far away as Morocco, Algeria and Yemen.

The volunteers made their way to Syria — some directly from their home countries and others by way of Egypt or Turkey — where they linked up with the coordinators. Some coordinators charged up to $2,500 to help the volunteer fighters reach Iraq.

Once provided with passports and other documents, the volunteers traveled to border areas, where they entered Iraq on foot along with guides from local tribes.

Since 2004, Abu Ghadiyah has organized and supervised much of that traffic, according to U.S. officials.

Interestingly, U.S. officials say they believe that Syria has tried from time to time to crack down on the smugglers and tighten controls along the 350-mile border, bolstering security patrols and erecting sand berms.

But Syria has been unable to keep up the pressure, in part because its government needs support from local tribes and revenue from the bribes the smugglers pay to local officials, according to the Combating Terrorism Center study.

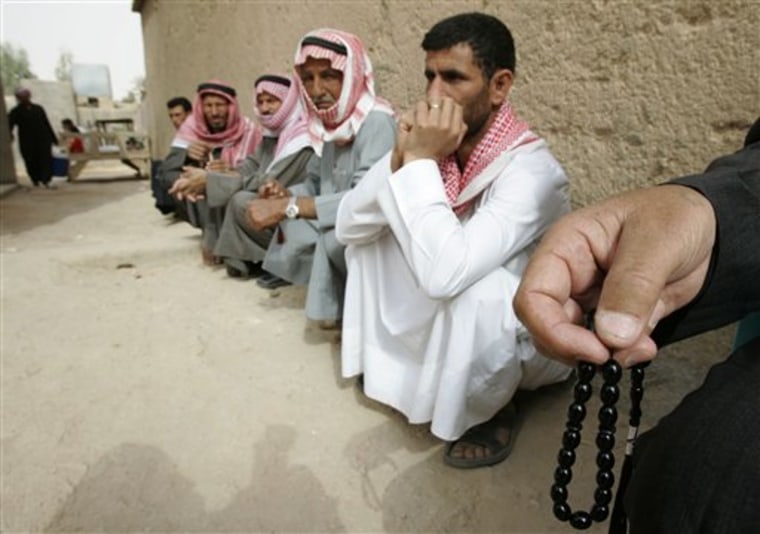

Those sensitivities are apparent in Abu Kamal, where people wear traditional Iraqi clothing and speak with Iraqi accents.

"Most of the inhabitants of the area originally come from areas of Iraq, and there are very strong family ties until this day," said Ahmed al-Khalifa, a lawyer from Abu Kamal. "There is strong sympathy here with whatever happens in Iraq."

New wave

Even before the insurgency began, those feelings of kinship encouraged hundreds of volunteers from eastern Syria to pass through Abu Kamal to Iraq to defend the country against U.S. forces in the 2003 invasion.

After Saddam Hussein's regime collapsed, Syria set up new checkpoints around the town to prevent more volunteers from getting to Iraq, the terrorism center report said.

But Syrian public outrage over U.S. attacks against Iraqi Sunnis in Fallujah in 2004 prompted the Syrians to relax the restrictions and allow more fighters — this time many of them Saudis — to enter Iraq, the report said.

A third wave of volunteers began in 2006 as fighting between Iraqi Sunnis and Shiites intensified, the report said. The current wave is continuing, although at a lower level because many Iraqi Sunnis have abandoned the insurgency.

There may be plenty of others to take Abu Ghadiyah's place, the U.S. says — including a brother Akram, and a cousin Ghazi Fezza al-Mazidih, whom the U.S. described in a February report as his "right hand man."

Overall, the number of foreign fighters attracted to Iraq may be down, the West Point study cautioned, "But the logistical network to move them has become more organized."