Just shy of two decades ago, Earthlight gleamed softly along the lower flanks of the bulky winged cylinder orbiting its home planet. As massive as a city bus, the Hubble Space Telescope raced around the night side of Earth. The brilliantly lit cities issued lights from below, while in the atmosphere itself, lightning bolts and streaks from meteors burned fiercely.

Despite being shrouded by the planet's shadow, Hubble reflected the bright pinpoints of stars gleaming everywhere in the velvet black sky.

Hubble was a dream started decades earlier. In 1946, Princeton astronomer Lyman Spitzer urged America to build a space platform with revolutionary instruments to probe the universe. No matter how powerful the telescopes of Earth were, they would never see clearly through our thick and pollution-muddied atmosphere. A telescope orbiting high above Earth could survey the heavens with unprecedented clarity.

But once in orbit Hubble was sidetracked with flawed vision and shuddering vibration. Two months after its fiery ascent from Cape Canaveral in April 1990, embarrassed astronomers admitted that the telescope's goals were seriously compromised. Some systems worked well, but not the critical scientific packages.

The most celebrated telescope since Galileo assembled his first optical instrument was sending blurred images back to Earth and Hubble's team began dreaming up risky schemes to eliminate the blunders. The Corrective Optics Space Telescope Axial Replacement, or COSTAR — a "fix-it effort" to be done with mirrors — was born.

Massive fix-it

The space shuttle Endeavour with a crew of seven departed Earth on Mission 61 at 4:27 a.m. ET on Dec. 2, 1993.

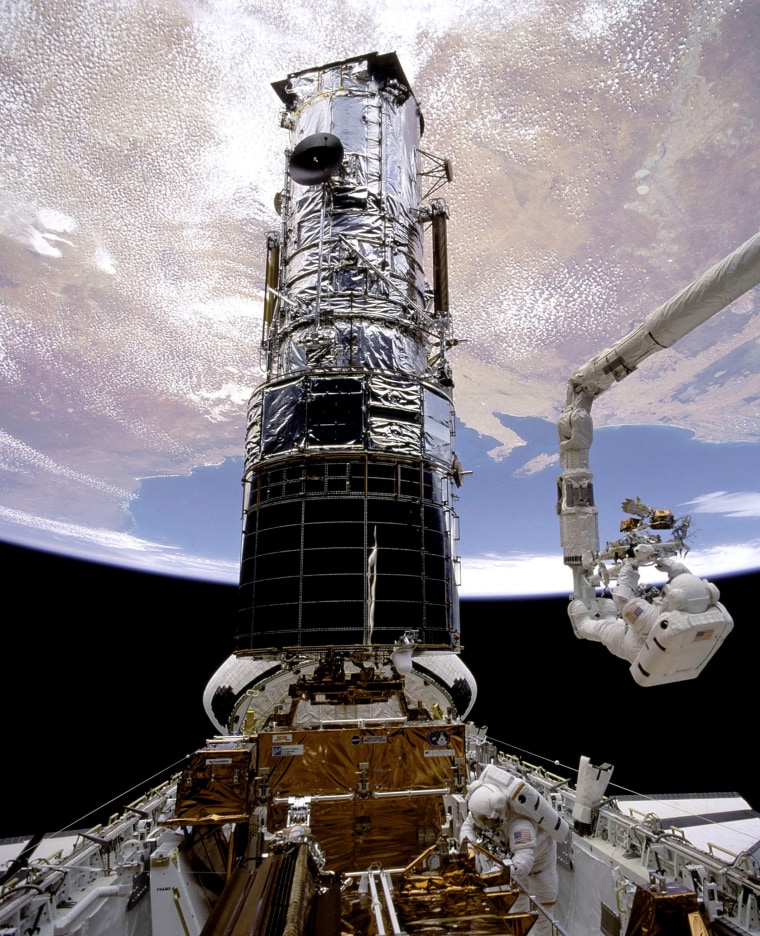

When the shuttle reached Hubble, the astronauts captured the observatory with Endeavour's robotic arm. Spacewalkers, working in pairs, went through an astonishing week of giving the crippled telescope new life and sparkling accuracy.

Floating 375 miles above a curving horizon, appearing as if they were living snowmen, the astronauts performed weightless ballets to make their repairs. It was a feat unparalleled in history. Spacegoing surgeons operated beneath a star-filled theater.

Eight days passed. Endeavour and her crew were back on Earth. Hubble managers waited fretfully to find out if the space surgery was as successful as promised.

Then the last fetters of Hubble were removed. Power was fed to controls and instruments. The space observatory moved through its checkout commands. Hubble was again alive.

Astronomers gathered in front of a television monitor in the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore. The control center had all the tension of a maternity ward waiting room.

Light surged through the screen, flickered, then steadied. There — the first image. Star AGK +81 D226 . . . clear, sharp, beautiful. For moments silence gripped the room. Then tension. Followed by back-slapping, applause, cheering. Astronomers hugged one another fiercely.

Three men and one woman. Endeavour's spacewalkers had corrected Hubble's vision to even greater sharpness and clarity than its creators had ever hoped. Robert Hager, my NBC News colleague, turned to me and said, "It's amazing what you can do with a $629 million pair of contact lenses."

Closing in on creation

Following 1993's corrective lenses fix, astronauts returned three more times to service Hubble.

In 1997, 1999 and 2002 they installed better cameras and made improvements. America's far-seeing eye gave us breathtaking vistas of every corner of the universe including the celebrated image of Eagle Nebula, a star-studded region 6,500 light years away. The pictures were instantly called the "Pillars of Creation," and because Hubble is really a time machine, the Eagle Nebula images we see were formed 1,500 years before the Pyramids were built.

From the Eagle Nebula, Hubble turned its eye to events and places millions and billions of years old. The farther it looked, the closer it saw creation's infant steps following the big bang, history's most important singularity. The telescope was coming closer to the instant the universe began.

Hubble shed light on the age of creation (13.7 billion years), and it has shown us galaxies upon galaxies expanding quicker than before. It has shown us the effects of massive black holes and dark energy. It has outlined the very web that is holding the universe together, looking back across 12.9 billion years, 94.16 percent of existence itself.

Today this famed eye, this magnificent machine is showing its age. Three of its major instruments are broken. Half of its six gyroscopes needed to place Hubble on target have failed. Its batteries are slowly dying.

But if this final servicing mission works, if the new instruments come to life in Hubble's bowels, the new eyes will take astronomers to within 500 to 600 million years of the birth of the universe.

Wouldn't it be great if we could see the creator sitting on the birth star waving at us?

Jay Barbree, NBC News' Cape Canaveral correspondent, has covered the space effort for more than 50 years. His most recent book is and he is also the co-author of