The county of Fermanagh is quietly making its way onto Ireland’s tourist map. For years, wealthy visitors from Germany and Switzerland have spent their summers cruising the idyllic Lough Erne with its wooded islands and wild birds, and now people are coming from farther afield to enjoy fishing and walking holidays. Yet not so many years ago, southwest Fermanagh’s green pastures were known as the “Killing Fields.”

In part of the county land bordering on Northern Ireland’s County Tyrone, more than 170 people have died in political violence in the past 30 years. At least 100 of those were local Protestants killed by the Irish Republican Army, usually because they were members of the locally organized Ulster Defense Regiment, a part-time, mainly Protestant unit of the British forces in Northern Ireland.

At the height of the IRA campaign of violence in the 1970s, a number of Protestant farming families left their lands on the border and moved to safer territory farther north. Even today, some Protestants talk of “ethnic cleansing” in the belief the IRA systematically drove them out of the border area.

It’s the reverse of the pattern across Northern Ireland as a whole, where twice as many Catholic civilians as Protestant civilians have been killed, and where Catholics in the east of the British province were driven from their homes by loyalist extremists. But there has nonetheless been a marked demographic change along the frontier. A study by researchers at Belfast’s Queen’s University found that the Protestant population along the north side of the border declined by 12 percent between 1971 and 1991, while the Catholic population increased by 29 percent.

Yet Protestants and Catholics alike talk of the excellent community relations that existed between ordinary people in the formerly mixed border villages. One Protestant farmer who stayed put was Tommy Ovens.

Now 72, Ovens served part time in the Ulster Defense Regiment for more than 40 years, going out on patrol with his local unit and attending briefing meetings sometimes as far away as Scotland.

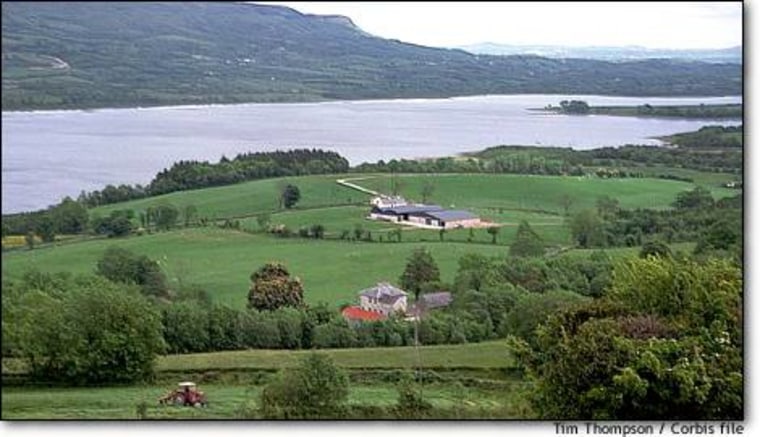

His dairy farm near Belleek stands on the shores of the breathtakingly beautiful Lough Erne and commands views of the forests and lakes beyond. Living just 4 1/2 miles from the border with Ireland made him one of the most vulnerable Ulster Defense men in the area.

At the height of the Troubles, the IRA planted a bomb on his tractor that nearly killed his son.

“I came in that night and I got a worried feeling over me about my home, and I got down on my knees and I prayed ... that everything was all right. At 4 a.m., there got a big heavy gale (that triggered) the bomb and it exploded.” Only a few hours later, his son would have started to work on the tractor, Ovens said.

Yet even while serving in the Ulster Defense Regiment, Ovens says he enjoyed good relations with his Catholic neighbors. He is a wholehearted supporter of the Good Friday agreement and has high hopes for peace in Northern Ireland.