Venezuela’s president Hugo Chavez is prone to small acts of great kindness. Every Sunday during his call-in radio program “Hello President,” Chavez scrambles his staff to help the downtrodden or destitute. A woman who couldn’t pay for an operation grabbed Chavez’s attention one recent morning. “We beg you to help with our everyday life,” pleaded another caller, a victim of last year’s deadly floods. But the president is not content healing only small wounds. Hugo Chavez is plotting a revolution from behind this microphone. And Washington is worried.

These weekly radio broadcasts have become stream-of-consciousness brain-storming sessions for the president. For 3 1/2 hours on this hot and sticky Sunday, Chavez promises housing developments in the Andes, a new school curriculum and affordable health care for all.

The man who eight years ago was locked up after a failed coup is bursting with ideas on how to better the lives of Venezuelans, half of which live in dire poverty. Much of what he says sounds reasonable.

Even those who mock the weekly radio melodrama concede that Chavez is sincere. The intimacy between the president — a plain-speaking former paratrooper — and the people has paid off.

“Venezuela supports Chavez because we look at him as a person who can make our dreams come true,” says Alberto Castelar, a student at Central University in Caracas.

Still, Hugo Chavez’s sky-high approval ratings and particular brand of populism are fragile. They depend on a “social revolution” financed by oil.

Petro-power, petro-peril

Oil is an unreliable partner in revolution. As long as petroleum prices remain high, Chavez can afford some of the promises that swept him to power two years ago. But, many factors conspire against $30 a barrel oil, and the United States is not the least of them.

“I must warn that there are countries that want us to give oil away at $8 to $10 a barrel,” Chavez said during a recent broadcast.

Venezuela has the largest oil reserves outside of the Middle East and is America’s third-largest foreign supplier. Last year, 14 percent of all the oil the United States imported came from Venezuela. Conversely, Venezuela’s biggest customer is the United States. It is, in many respects, a mutually dependent — but prickly — relationship.

Since his election in December 1998, Chavez has been lucky. A trebling of oil prices has added billions of dollars to Venezuela’s economy. The 46-year-old president’s pugnacious defense of his fellow OPEC partners, in the face of intense pressure from the United States, has been credited with unifying the oil cartel and sparking the price surge.

At the same time, Chavez’s oil activism has propelled him onto an international stage. His berating of the United States for its “savage capitalism” and selfish consumerism at the expense of poorer nations, has transformed him into a would-be champion of the developing world — a Fidel Castro in the making.

If these rhetorical volleys against the United States hit a nerve in Washington, the Clinton administration barely flinched.

Even Chavez’s political maneuvers, eroding the democratic power of the legislative and judicial branches at home and undermining U.S. interests in the region, evoked little response from Washington. As opponents branded Chavez a kind of elected dictator, the Clinton administration quietly observed.

Now, after two years of tolerating Chavez for the sake of oil, analysts close to the new Bush administration believe U.S. policy toward Venezuela will soon turn tougher.

The populist hero

“At the end of the day you have to ask, ‘What will getting tough get you?” says Bernard Aronson, former assistant secretary of state for Latin America in the previous Bush administration.

A disruption of the oil arrangement with Venezuela could do a great deal of harm, he argues.

Others agree, advising a continuation of the Clinton policy of positive engagement, especially in a period when a disruption of oil supplies could further teeter the already weak U.S. economy.

What’s more, Aronson says, a get-tough policy now could provide a convenient excuse for Chavez to continue to consolidate his authority even if his petroleum-powered social revolution doesn’t pan out.

”[Chavez] would like to inherit Fidel Castro’s legacy as the Latin leader who can stand up to the gringos. And because he cannot deliver all the promises he made to his constituents, he would not mind having someone to blame — the U.S. is convenient.”

It plays like an old Latin standard. In many respects, Hugo Chavez is a throwback to an earlier, more confrontational period in U.S.-Latin relations when left-wing, jingoistic leaders dominated the region and the United States was their easy adversary.

“It’s always worth a few votes to be anti-American in Latin America,” says Richard Gott, author of “In the Shadow of the Liberator,” a study of Chavez’s rise to power.

The anti-Americanism plays well in Venezuela, where the rich-poor divide is so obvious and so daunting. But the stakes of that game are high, both politically and economically.

‘Chavez wants to help’

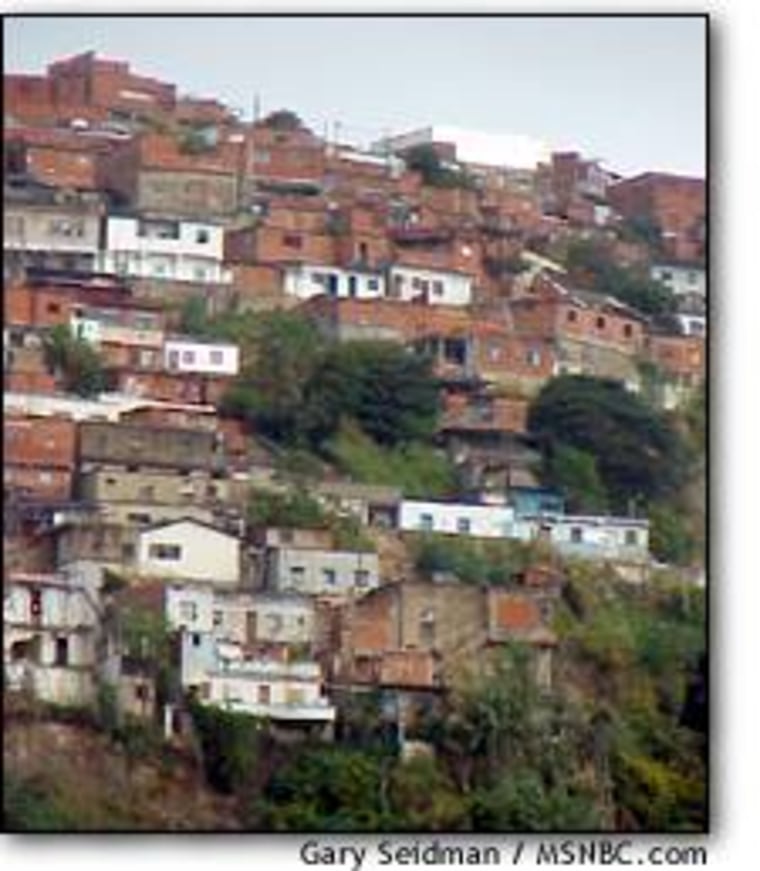

On a busy shopping street in Caracas, a barefoot young mother with a baby slung on her shoulder goes from car to car at a stoplight begging for change. “Chavez wants to help us,” she says, declining to give her name or age but motioning that she lives in a shantytown on a hill overlooking the city.

The woman — really a girl of about 16 — is the kind of would-be voter who got Chavez elected by a landslide in 1998. She is among the 50 percent or more of Venezuelans who live in poverty and have grasped onto the president as a potential savior.

It is the failure of a series of previous presidents to address the abject poverty in Venezuela that some political analysts say gave rise to Chavez and his populist, leftist notions.

“People feel he is one of them and he feels he’s one of them,” says Robert Bottome, who publishes VenEconomia, a Caracas newsletter that is severely critical of the president.

“The guy is a 1960s Marxist,” he says. “He’s talking 1960s issues with a 1960s vocabulary and 1960s perceptions of the world,” Bottome says. “Neither [Chavez] nor any of his advisers have learned anything from the last third of the century.”

It is not hard to find evidence for Bottome’s charges. Chavez ridicules globalization and market reliance for Venezuela, saying it doesn’t make sense in such a poor country. Instead, he has pursued a domestic policy based largely on farm projects, food production and rural development. Some of his oil money, he says, is being diverted into projects like those housing developments in the Andes.

To the young mother it sounds promising. To Washington, it sounds like a dangerous, new, oil-powered Castro.

Nuisance or threat?

If it weren’t for Venezuela’s abundant oil, Hugo Chavez might well have been treated with the same insignificance as many of America’s other “partners” in the developing world.

A high-profile visit to Iraq’s Saddam Hussein and a showy relationship with Cuba’s Castro has made American policymakers wary of Chavez’s international intentions. His refusal to cooperate with a billion-dollar U.S. drug eradication program in neighboring Colombia, arguing that the guerrilla war will spill into Venezuela, has added to the friction. So has his deal to provide Cuba with monthly supplies of oil, and his polite rebuff of American aid after the Christmas 1999 floods that killed tens of thousands of Venezuelans.

But it is Chavez’s constant allusion to a Bolivarian Revolution — a reference to the 19th century Latin “liberator” Simon Bolivar, who promoted a continent-wide crusade against foreign imperialists — that prompts the most concern in Washington.

Last December, in a rare moment of State Department candor on Venezuela, Peter Romero, then the top official in charge of inter-American affairs, told the Miami Herald that “there are indications of Chavez-government support for violent indigenous movements in Bolivia.” After two years of carefully avoiding a dispute, the remark was a lightning bolt. Suddenly there was a voice to growing U.S. concerns that Chavez was trying to export his “social revolution.”

Still waiting for results

Whether that resonates in the new Bush administration is questionable, but it comes at a time when Chavez’s honeymoon at home is showing signs of ending.

“The problem with the president is that he has been here for two years but you don’t see the results and the poor don’t see the results,” says Alexander Lopez, an early Chavez supporter who heads the political science department at Central University. “It’s not the same as six months ago or a year ago.”

The government counters that social revolution takes time and that two years isn’t enough to turn around a poor country with long neglected and brazenly corrupt institutions — regardless of Venezuela’s oil wealth.

But Eric Ekvall, a political consultant who has worked for numerous presidential candidates throughout Latin America, contends that Chavez is dangerously out of touch.

He is pursuing an anti-modern, anti-global, anti-capitalist model for Venezuela that is increasingly alienating the country from the capital that it dearly needs, Ekvall says. “What this country needs is oodles and oodles of entry-level jobs for people.” What he’s offering are handouts and promises and empty dreams. Every Sunday, people walk away from their radios, Ekvall says, and they think: “I’m going to be next.”