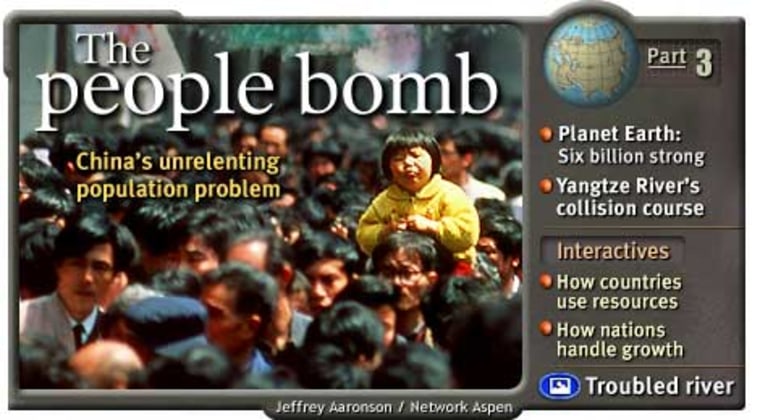

“It is a good thing that China has a big population,” Mao Zedong stated with confidence in 1949. “Even if China’s population multiplies many times, she is fully capable of finding a solution,” he said. Today, China’s leaders are still looking for that solution, and as the Chinese move up the economic ladder, their problems become the problems of the world.

While Mao put advocates of population control behind bars for their pessimistic forecasts, post-Mao China has taken drastic - many would say Draconian - steps to put the brakes on population. But even with its legendary One Child Policy, China adds an estimated 14 million people each year. That is more than the total population of Florida, or the combined total populations of Norway and Sweden.

It’s not that Beijing’s efforts were a failure. On average, women in China have just 2.5 children each - a low rate among developing countries. But the population of women now in their childbearing years is massive - about 350 million - and people are living longer. Controlling growth at this point is like bringing a runaway freight train to rest.

Even if Beijing’s tough birth control policies hold sway - which is by no means certain - the population may rise to about 1.6 billion by 2050 before leveling off.

What if they prosper?

Now imagine a billion people moving from a simple agrarian lifestyle toward a life with all the latest conveniences.

Following the lead of the West, Chinese people are eating more meat, buying private cars, building skyscrapers, burning more coal, using more water, cutting more trees and dumping more waste.

Its massive population is what makes China’s industrialization different than Western industrialization in the last century. According to China’s own statistics, the amount of land, farmland, grassland water resources owned by each individual Chinese is less than one-third of the world’s average figure. Forest and oil resources per capita are just one-tenth of the world’s average.

“China cannot afford to get rich first and clean up later,” said Ho Wai Chi, executive director of Greenpeace China.

“It must urgently invest in clean production technologies, energy efficiency and renewable energy programs if it is to avoid an environmental meltdown,” he said.

Environmentalists and population experts argue about the degree and timing of China’s problems, with predictions for China’s environment and quality of life ranging from unhealthy to catastrophic.

But China is by no means alone in its dilemma. Particularly in the developing world, many countries have just started to look at their growth rates, and are only now beginning to offer birth control services to their people. In sub-Saharan Africa, for example, population growth is mostly outpacing economic growth, intensifying poverty. And India, growing by 15 million people a year, is likely to surpass China as the most populous nation in the next few decades.

How Beijing handles its challenge could be instructive around the globe.

Chain reactions

In any scenario, the world will be affected by how China deals with its dilemma. Not only are China’s farmland and water resources in short supply and its ecosystems imperiled, but the nation’s growing consumption is measurably straining resources and environments outside its borders.

In one of the gloomiest — and most hotly contested — forecasts, Worldwatch Institute’s Lester Brown suggests the situation in China could lead to an international food crisis.

Beijing does not deny the seriousness of these issues, but there are so many of them and little room to maneuver. Also, solutions to one set of problems tend to beget others.

“This is the lose-lose proposition of a large population,” said Robert Engleman, vice president for research at Population Action International. “Past a certain point it gets harder to find no-cost solutions. All solutions have unintended side effects if you fill a country the way China is filled.”

For example, China has done remarkably well at producing large amounts of food on comparably little land. As its leaders are eager to tout, the country has remained reasonably self-sufficient for grains, supporting one-fifth of the world’s population on just one-eighth of the world’s arable land — the small slice of eastern China that supports the vast majority of its billion people. Most of the country is made up of mountains or desert, regions barely habitable, much less arable.

But the dramatic gains in agricultural productivity in the 1980s are leveling off and the last decade of intensive farming, marked by the highest use of chemical fertilizer and pesticides in the world, is now destroying farmland.

In Zhaozhou county, home to about 330,000 farmers and ranchers in northeast China, about one-quarter of the land area turned to an impermeable crust after overgrazing caused a chemical change called alkalization of the soil. Another portion of the land used for crops suffers from “soil burning,” which takes place when chemical fertilizers are used but organic matter is not restored to the soil, as it was in the past when manure served as fertilizer.

“The decline of organic matter in soils is probably more crucial than most of the issues that make the headlines,” said Josh Muldavin, a geography professor who chairs international development studies at University of California Los Angeles.

Muldavin has been working with the Zhaozhou farmers to rejuvenate the soil, but remedies are very expensive and can take decades. “Things can be done but they’re difficult,” he said. “At the same time, economic policy is pushing people to increase production.”

A better publicized problem is that rapidly growing industrial areas have gobbled up vast amounts of farmland - about 1 percent per year in the 1990s. This is even worse than it appears, suggested Muldavin. “Unfortunately, the marginal land is in hinterlands, and is the last to be converted (to industrial uses). Some of the richest farmland is in areas that are rapidly urbanizing, primarily in the north China plain. The best farmland is being converted.”

The trend has set off alarms in Beijing: China’s elderly leaders have all witnessed famine in China in their lifetimes. But directives to limit the loss of land have proven difficult to implement and hard for local government officials to enforce. Power and wealth, after all, lie in the hands of the industrialists, not with the farmers.

Most economists agree that China will likely need to import more grain, though China’s leaders - fearful of political implications - are loathe to do so. And China’s entry into the international grain market would raise prices for the entire world market.

Water wars

Seen from the halls of power in Beijing, the country’s most pressing problem is to keep the economy rolling ahead. It is the issue upon which dynasties have risen and fallen, and China’s elder revolutionaries know their history.

Early experiments in private enterprise originally took root because of a crisis in the countryside. There was a desperate need to provide alternatives for people living in rural areas, which at that time made up some 90 percent of the population. Farms had been divvied up ever smaller over the generations (except during a short period of collective farming) until the average plot was a tiny noodle strip of an acre or less.

Blossoming factories around the country have absorbed hundreds of millions of people and dramatically raised living standards across China.

Largely because of these factories, economic growth has been stunning — nearly 10 percent a year for two decades. To absorb vast armies of people from the countryside, and those laid off from unprofitable state firms, China needs to keep it all moving forward — fast.

But industry and rising soaring urban consumption are already on a collision course with agriculture as the two sides vie for scarce water supplies, especially in the arid north.

A growing population of city residents has driven demand sky high — access to private showers alone makes a huge difference. Add in luxuries like washing machines, beer, Coke, and swimming pools, and the problem of consumption becomes understandable. Water tables are falling one to three meters a year in some urban areas.

Farmers are facing a more desperate situation. With alarming frequency and greater duration, the Yellow River, one of the main water sources in the north, runs dry before it meets the sea.

In some places, the farmers continue to pump what is basically untreated sewage into the fields. Meanwhile, other rivers have disappeared. “They have sucked everything up,” said Daniel Gunaratnam, a water specialist at the World Bank in Beijing.

Water - the shortage of it in the north, the pollution of it in the south - may be the country’s most pressing problem. Water has been named one of the top challenges for the country by China’s most prominent man of action, Premier Zhu Rongji, but putting in place an integrated plan involves countless trade-offs.

One partial solution comes from diverting water. China has some of the world’s biggest projects of this kind under way, including three canals that will move water from the Yangtze River in the south some 800 miles north to the parched Beijing-Tianjin areas, home to some 20 million.

“The future of China depends on how they solve (the water) problem,” said Gunaratnam.

Air pollution

The air pollution produced by China’s economic transformation has been equally stunning, and in some cases, legendary.

The country has some of the worst air quality standards in the world, a factor, health experts believe, behind the soaring rates of asthma and other respiratory disease. The northern city of Benxi finally drew the aid of international agencies when it disappeared off satellite images because it was buried beneath a thick, acrid cloud.

After a seven-year effort, Benxi is visible again. But China’s reliance on coal - dirty, but cheap and plentiful - is not going away. Coal provides about 75 percent of the country’s power supply, and demand for power climbs with each passing year.

Japan, which has been affected by acid rain generated in China, has provided scrubbers and other clean-coal technology. Widespread use of these technologies can make a substantial difference in air quality, but their use affects the bottom line. There are persistent reports of factory managers turning scrubbers on only for inspections, because running them raises costs.

Economists say coal is too cheap, which encourages inefficient use. But as the United States and other countries have discovered, lifting subsidies on energy is politically unpopular and slows economic growth.

Ultimately, China will need to make a major shift, as indicated by a World Bank report from the northern province of Liaoning.

“The air quality problems here and in other cities of Liaoning Province are too severe to be solved soon, or at reasonable cost, by emission controls alone,” it reported. “Reducing air pollution will require action at all stages - beginning with finding different sources of fuel.”

The greening of the reds?

In the face of multiple crises, China is rethinking many of its most dearly held beliefs - from its food security policy to its views on non-governmental organizations.

In the last few years, Beijing has allowed several independent green groups to form for the sake of education, and to some extent, to monitor industry compliance with regulations. It has tolerated the existence of Greenpeace China in the autonomous region of Hong Kong, despite the parent organization’s penchant for public protest.

There are even signs that Beijing is rethinking its approach to limiting population growth. International population experts now insist that people, even poor people in the developing world, don’t need to be forced to have smaller families as China has done.

“The idea that poor people want more children for security is largely a myth,” said Joe Speidel, population expert at the Hewlett Foundation. “Most growth comes from a lack of access to family planning. If people know they have an alternative, most will now choose to have a smaller family.”

There are also growing signs that China itself is subscribing to the view. Though it has not abandoned the One Child Policy that drew scathing criticism, in 1994 Beijing signed onto the Cairo Program of Action. The 179 signatories agreed to implement population programs that disband target numbers, abandon coercion and provide education. China’s signing onto the program helped the U.N. Population Fund Program to win renewed funding from the U.S. Congress, which had been withdrawn due to UNFPA involvement in China.

But at this point, even with ideal programs, it will be generations before China can see the gains. In the meantime, it will need equally creative means to stretch resources for its people.