Never has coffee as a commodity been cheaper than it is today, earning huge profits for the companies that roast and market the beans. And never have the farmers who grow the crop been so poor. While more than 400 billion cups of coffee are sipped and savored every year - more than any other beverage except water - little of the profit trickles down to the farmers.

What you pay at your local Starbucks for a double latte is more than a typical coffee picker earns in a day. Most of the world’s coffee is grown in Third World nations in Latin America, Asia and Africa. On small plantations, most pickers earn under $2 a day.

Today, coffee ranks just behind petroleum as the world’s second-most traded legal commodity, worth double the value of tea and cocoa combined.

But despite the increased demand for gourmet blends and the phenomenal expansion of coffee houses - Starbucks has more than 5,000 outlets from Seattle to Seoul - international prices for coffee beans have bottomed out, partly because there’s close to 2 billion pounds of surplus beans.

Standard-grade beans currently fetch barely 50 cents per pound on international commodity markets, which adjusted for inflation is the lowest price ever for coffee.

But at the source, middlemen sometimes pay half that amount in hard cash to the credit-strapped farmers who grow the beans.

Desperate for money

Average retail prices for coffee have dropped only 27 percent, but farmers get paid just one-fifth of what they did five years ago for their crops. Overall, 90 percent of the profits from the coffee industry go to the traders and retailers.

Farmers are so desperate for money that a 14-member international coffee cartel founded to stabilize prices was forced to disband this year because so few growers would hold back bumper crops of beans and risk a further fall in prices.

Meanwhile, companies that process and market coffee are profiting immensely from today’s low prices.

Four global giants — Nestle SA of Switzerland, Procter & Gamble, Kraft Foods Inc., and Sara Lee — dominate the industry by handling nearly 40 percent of the world’s coffee. They purchase coffee in bulk and then roast, blend and grind it into supermarket brands such as Nescafe, Folgers or Maxwell House.

In an effort to prevent the spread of communism in coffee growing nations, the United States used to prop up crop prices during the Cold War. Now, free-trade policies allow these corporate giants to buy directly from the plantations, where in the spirit of capitalism, they buy for the cheapest price possible.

But the major coffee players say they also try to help farm communities by purchasing part of their beans directly from farmers so they receive a fair price for their crop. Some corporations say they also give money to local schools and health clinics.

Leaving the land

Still, a recent survey by the World Bank estimates that 540,000 laborers in Central America have lost their jobs because of coffee’s low market price. Landowners are making do with subsistence plots of corn and beans, but malnutrition is rife.

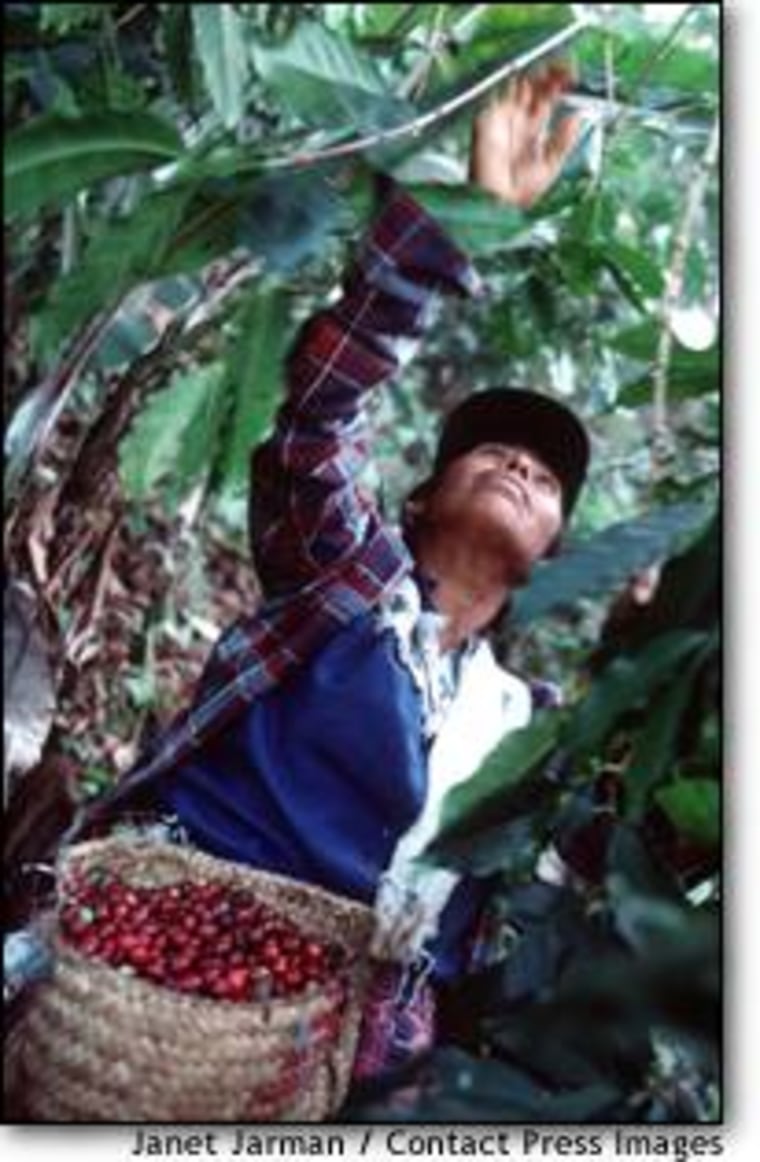

The Mexican village of El Paraiso, in Guerrero state, used to live up to its name as a paradise. Under a canopy of banana plants and shade trees, red coffee cherries ripened before families picked and dried them for market.

But many farmers say it’s not worth cultivating the trees anymore. “The price we get for coffee is nothing,” says one, Ignacio Catalan Catalan. “I haven’t seen conditions this bad in my whole life.”

In despair, his neighbor, Hilberto Ortiz Adame, killed himself in May.

More lucrative cannabis and opium poppy crops are increasingly replacing coffee, ratcheting up rural violence.

Now, many workers are abandoning their villages to look for a better life in Mexico’s cities and in the United States. Half the 14 undocumented Mexican migrants who died in May 2001 trying to cross Arizona’s brutal desert together after their guide abandoned them were coffee workers from Veracruz state.

A piece of the action

Farmers believe that one way to get a bigger share of the profits from coffee is to get rid of gouging middlemen and go directly to export markets, where organic and specialty beans can fetch higher prices.

Tasty Nicaraguan coffee drew raves at coffee auctions this summer, where beans from San Isidro and El Regreso plantations went for $11.75 per pound - more than 20 times the current commodity price.

“The farmers were stunned. ... They were only offered only 20 cents per pound on the local market for this crop,” trader Steve Hurst of Mercanta Coffee Hunters told reporters before buying up as many of the sacks as he could.

Starbucks has started stocking cooperative-grown Fair Trade beans on the shelves of its U.S. stores, but the company doesn’t use the pricier beans to make its espresso drinks, where it makes its real money. A measure on the November ballot in Berkeley, Calif., would outlaw the sale of coffee that is not labeled “fair trade,” a designation given to products by a global movement to assure that growers get a good price for their crops.

Growers say that marketing coffee more like wine could help increase gourmet coffees’ paltry 15 percent of the global market share. “We need a seal of quality like the ‘appelation controlee’ in the French wine business,” said Marcelo Vieira, a Brazilian grower.

Additional reporting from Janet Jarman in El Paraiso in the Mexican state of Guerrero.