Don Kranz sits in his other office — his car, that is — describing his work schedule. As an Oswego, N.Y., manager at consulting firm PROCESSexchange, which helps companies improve their technology methods, he’s always juggling his time — half on the road, half at home. The good part, he says, is the chance to catch his daughter’s cheerleading competitions. But there’s always work waiting. “I haven’t done a 40-hour work week in the last four or five years.”

Kranz's schedule is flexible, but not light. Work often comes home. “You want 40 billable hours a week,” he says. “Then you have management time and marketing time, and that’s all done above the 40 hours you’re billing.”

Such are the tradeoffs of modern working America. There was a time — first during the Great Depression, then in the postwar years — when the 40-hour week was an American staple. But those days bear little resemblance to today.

For one thing, employers nowadays frequently find it easier to add hours to workers’ schedules than to hire, train and provide benefits to a new employee. Employees, meanwhile, rely on comp time, employer flexibility and technology to remold their schedules in ways never envisioned in the past. A globally connected economy has made “9 to 5” little more than the name of a 1980 film. With the economy ever more service-oriented, the line has blurred between the average wage-earning, coveralled Joe and his salaried, tie-wearing boss. Not only is Jane likely off the factory floor, but it’s hard to tell whether her collar is blue or white.

All these changes have targeted two competing visions of the American workplace. In one, you do your 40 and leave. In the other, hours matter less; responsibility lies with the worker; company goals and the bottom line are what count.

That split used to be clear and class-based — unions duking it out with management. But a huge and growing middle class, and the changing nature of the economy, have thrown old definitions into disarray.

“The social contract is shifting,” says Susan Meisinger, president and CEO of the Society for Human Resource Management: “For the jobs that fall into the category of knowledge worker, I think the lines are much blurrier.”

And that blurriness lies at the heart of proposed new rules for overtime advanced by the Bush administration — possibly the biggest change in decades to laws governing the work week. The new rules could provide overtime to more than a million low-wage workers, if Labor Department estimates are correct. But the rules could also curtail overtime pay for many workers whose jobs reside in the modern economy’s gray areas.

The work week through the ages

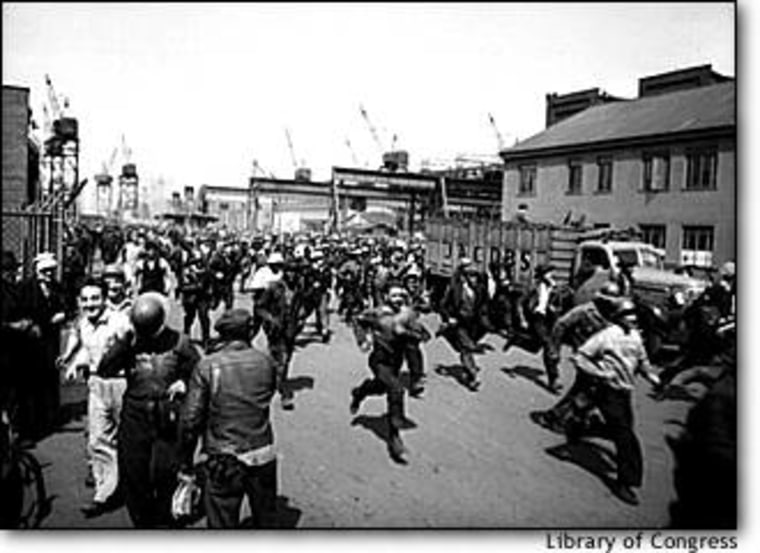

The 40-hour week is anything but hardwired into American culture. Through World War I, Americans largely worked a six-day week. Unions pushed for decades to shorten that. They finally succeeded during the Great Depression — in part to help corporations preserve jobs by spreading work across more workers.

In 1938, when the Fair Labor Standards Act was passed, it included a 44-hour cap before overtime kicked in; the 40-hour limit didn’t come until 1940. Then, during World War II, work hours soared as companies sought to maximize production for the war effort.

After the war, the average work week leveled off. The very concept of overtime was largely designed to drive employers toward a standardized work week by making it expensive to keep workers on the job too long. That idea succeeded at first, but the data are less clear about the long-term impact. By one tally, work hours have been dropping since the mid-1960s, from an average of 38.4 hours in 1964 to 33.8 hours earlier this year. But manufacturing jobs are averaging just above 40 hours, almost exactly where they were in 1946. And average overtime is rising. Service-sector workers average fewer hours, but because many are part-timers, conclusions about the hours in the average work week are harder to come by.

Still, longer hours are a reality for many Americans. Economist Peter Kuhn at the University of California, Santa Barbara, finds greater numbers of men now work over 50 hours a week — most of them highly educated, well paid, white-collar workers. Though numbers leveled off in the 1990s, one-fifth of American men work those hours, up significantly from 25 years ago. At the same time, most get bigger salaries and bonuses, part of what Kuhn calls “the incentivization of white-collar work”: more compensation for longer hours and more job commitment, with implied penalties if you don’t give your all.

Indeed, that pressure to perform may have flipped the hourly balance. “It used to be that when you got a college degree you could get a white-collar job and take it easy,” Kuhn says. “It’s just the opposite now. It’s blue-collar folks who have more time for leisure.”

But that divide doesn’t mean what it used to.

'Management empathy'

Some companies still put workers and managers in different camps, but human-resource executives have argued for years that shared corporate goals are what’s truly important. “There are some companies that are what I would describe as Neanderthal,” Meisinger says, “because they don’t see the value of getting everybody on the same page.”

Many do get the gospel, though. International Survey Research, which surveys employees on their views about the workplace, has found corporations thriving on “management empathy.” These firms embrace feedback and let employees help set goals. It has to go beyond simple slogans and corporate can-do spirit, but when it works, productivity can soar and employees easily forgive extra hours. “They’re seeing tangible results, and they know that their management up the chain understands that they’re putting that in,” says ISR director Will Werhane.

In fact, employees at such companies — like Nokia, Microsoft (a partner in MSNBC) and Southwest Airlines — would often put corporate success before their own pay, in part because it meant they could gain more down the road.

In a way, that concept foreshadows the new overtime rules, which halt extra pay requirements for anyone in a “position of responsibility.” In companies where employees help set priorities, that could include a lot of people — and labor unions are worried it could mean even more work for many junior white-collar workers already burdened with heavy schedules.

To them, empowerment requires more than just shared goals. “If an employer tries to structure a workplace that in some sense does make employees owners … that’s one thing,” says Chris Owens, the AFL-CIO’s director of public policy. “It’s another thing altogether to think that, just because Wal-Mart calls its employees associates, that they are anything but hourly workers who need to get overtime.”

At the same time, many employers feel work laws are strangling their ability to be flexible — that, for example, they must either pay a worker overtime for a 50-hour week, even if the following week is just 30 hours, or break the law. Ron Bird, chief economist at the business-funded Employment Policy Foundation, argues that new regulations are needed to provide effective flex time or comp time. “The worst thing we could do is to try to enforce a one-size-fits-all solution for the workplace.”

Still, workers are feeling pressure on the job. Both manufacturing and high-tech employees told ISR that their workload was too heavy and they had trouble balancing their work and personal lives.

That’s a common theme in workplace studies. If the 1950s family breadwinner — almost certainly Dad — provided for his family on 40 hours a week, today’s working couple often more than doubles that in combined hours. University of Pennsylvania sociologist Jerry Jacobs points out that if one half of a couple exceeds 40 hours, his or her partner usually does too. More hours can provide more disposable income, but Jacobs finds that doesn’t necessarily translate into a better standard of living. “The salaries for a lot of these jobs have stagnated. The expectations while you’re working these long hours have gone up,” he says. “It’s putting a tremendous amount of pressure on family life.”

Many families have tried to adapt, of course. Frequently, one half of a working couple — still Mom, usually — opts to scale back: fewer hours, telecommuting or part-time jobs. Yet those decisions can often come at the cost of promotions or bonuses.

And many part-timers would like nothing more than to take more work. In surveys Jacobs conducted for an upcoming book on work-family balance, professionals putting in over 50 hours a week usually wanted to shave hours, while those working 20 to 30 hours a week felt underused.

Who’s behind this disparity? Employers, for one. When you consider that benefits account for 25 to 30 percent of each employee’s total compensation, fewer employees doing more saves companies big money.

Greater productivity is another reason. As workers do their jobs better and work harder, fewer new staff need to be hired — one reason economists think the recovery hasn’t necessarily translated into more jobs. Many firms found they could cap the workforce without losing productivity.

Yet Jacobs argues that strategy has its limits. The length of the work week soared during World War II, for example, but productivity in many factories plateaued as bosses found they couldn’t get much more from a worker doing a 12-hour shift than one doing 10 hours.

Is 40-hours history?

“Your surmise is exactly wrong,” says Daniel Hamermesh, a labor economist at the University of Texas at Austin. His view is that the brave new world of work — focused on goals, unbound by hours — is more fiction than fact.

According to his data, taken from Labor Dept. statistics, workers say they put in 42.7 hours a week in 1979 and 42.6 in 2002, and the percentage who worked exactly 40 hours a week rose slightly. Moreover, he argues, a perceived trend away from hourly wages to salaries simply hasn’t happened. In a 2000 paper titled “12 Million Salaried Workers Are Missing,” he noted that perceived trends toward a skilled, salaried workforce — more educated workers and skilled occupations, fewer manufacturing jobs and union labor — weren’t supported by hard numbers.

Hamermesh admits his findings are “mindboggling,” contrary to every expected trend. Some of the perception of more work, he posits, may come from those who already worked beyond 40 hours spending even more time at their desks. In other words, not everyone is working more, just those who already were.

Yet the composition of those would-be workaholics has changed. Many blue-collar jobs have morphed into the white-collar world, particularly in the information economy. For those folks, and their bosses, office walls often don’t hem in the job. High-tech tethers to the workplace — pagers, e-mail, take-home laptops — extend work weeks. It’s no longer enough to just tally up your hours at the office. Many employers now assume work can be done anytime, anyplace.

But many workers, particularly younger ones, are more concerned about work-life balance than money or advancement, ISR found. It may in part be a sign of how many recent grads became disillusioned with wired workaholism as the paradigm-shift hoopla of the ’90s was uprooted. “They’re not necessarily bought into the notion of work 80 hours and life will be grand,” says ISR’s Patrick Kulesa.

Even among corporate innovators, it’s harder to inspire loyalty. Nokia has faced layoffs. Microsoft ended employee stock options and signaled an end to many millionaire dreams. Southwest has been hammered by its unions, which want the airline to overhaul salaries and work rules. Unions also see the overtime changes, as well as the growing number of tech jobs being shipped overseas, as a rallying point. “The working conditions, while they’re not inside a factory, are in many ways every bit as exploitive as in the old-line factories,” says the AFL-CIO’s Owens. “I really do think that there is a change in the air.”

And so exists the American workplace, confused and complex, its workers unsure how long and how hard to work. U.S. employees still have some of the highest work hours among developed nations. There have been calls to echo European nations like France and Germany, where shorter work weeks were mandated as full-employment engines.

The 40-hour figure seems to be holding: Though they disagree about whether it should be law, both employers and unions acknowledge 40 hours as a cultural benchmark, something we’ve all come to accept. Still, those 40 hours are tallied in far more diverse ways and that flexibility can be tricky to accomplish. The overtime overhaul may simply hint at a larger fight to come over worker rights and pay. Companies want clarity on work rules and HR costs under control, but also want workers motivated. Employees want enough time to enjoy life, but not at the cost of a decent paycheck.

As Don Kranz drives his daughter to cheerleading camp, he considers the 10-hour days he’ll have the rest of the week to make up for it: “It is a balancing act.”

This was originally published August 25, 2003.