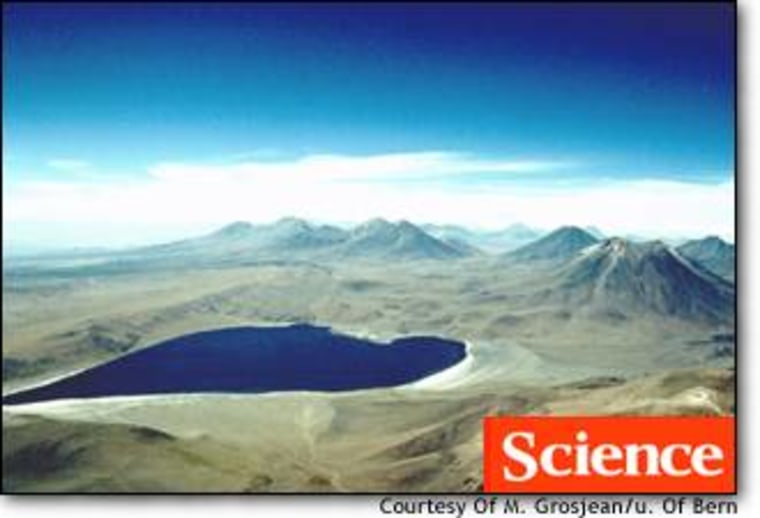

Today, Chile’s Atacama Desert is often called “the driest place on Earth.” In some parts of the desert, rain hasn’t fallen for centuries. Yet the climate in the Atacama has been positively pleasant during some of the time since humans first found their way across South America 15,000 years ago. In this week’s issue of the journal Science, published by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, researchers use that fact to fill in a 4,500-year gap in the story of the Atacama’s inhabitants.

Archaeologists studying the first peoples of the Americas had been puzzled for some time by ancient campsites unearthed in the Atacama.

The vast majority of evidence suggests that early hunter/gatherers arrived in North America from Asia or Europe, and gradually made their way across Central America and down into South America.

Yet the earliest traces of human activity at the southernmost tip of South America date to 14,600 years ago, almost 2,000 years earlier than the traces in the central Andes, where the Atacama Desert lies. What could explain this pattern? Had archaeologists simply overlooked older sites in the Atacama?

The new research suggests that in fact paleoindians arriving from the north initially “leapfrogged” over the barren Atacama, moving in only around 13,000 years ago when rainfall became more plentiful, lakes filled and vegetation grew abundant.

“When the first people came to South America, the central Andes were still completely dry: no water, no vegetation, no nothing. As soon as the climate changed from more arid to more humid, people poured in,” said Martin Grosjean of Switzerland’s University of Bern. “It makes sense, but this was the first time we could show that the events coincided,” he adds.

Trace the trek of the first Americans

Climate change, culture change

Since time immemorial, societies have risen and fallen. Some have left behind stunning sites like the pyramids of Egypt, the temples of the Central American Mayans, and the pueblos of America’s Anasazi. Others left little more than the remains of humble campfires and the game they ate.

Why were ancient settlements abandoned? Over the years, archaeologists have proffered explanations ranging from warfare to disease, pestilence and natural disaster. More recently, scientists have begun to believe that changing climate often played a role.

Studies of ancient climate show that global temperatures have been fairly consistent since the end of the last Ice Age, about 11,000 years ago. But the availability of water during this period has been anything but stable, which would have posed real challenges for ancient humans.

Reconstructing an ancient culture or a past environment is no easy feat. Doing both at once is harder still. Yet this is just the task that geoscientist Grosjean and two Chilean anthropologists undertook in the Atacama Desert.

In a commentary that accompanies the Science paper, Tom Dillehay of the University of Kentucky in Lexington lauded the team’s efforts to cross the traditional boundaries of scientific inquiry. “Paleoecologists don’t always read subtle human signals (if they existed) and archaeologists don’t always see specific environmental changes,” he observed.

How climate change kills societies

A prospecting tool

The first challenge for Grosjean and his colleagues was figuring out where to start looking in today’s vast, barren Atacama for evidence of people who lived there many thousands of years ago. Knowing that ancient peoples would have gathered near water sources, Grosjean’s team identified the locations of ancient springs, streams and lakes. “We started by reconstructing the environment, and then selected sites where resources were favorable 13,000 to 14,000 years before present,” he said.

Eureka! They discovered dozens of ancient firepits along the shores of long-ago mountain lakes. “This was proof that the reconstruction of environments may serve as a prospecting tool for archaeological sites,” said Grosjean. The team also explored numerous sites in mid-elevation caves and low-lying wetlands.

The excavations turned up charcoal, animal bones and projectile points. After dating these artifacts, the researchers determined that humans lived in the area primarily from 13,000 to 9,000 years ago, migrating seasonally from highlands to lowlands.

Interestingly, in the oldest layers of one cave site, the researchers found the bones of an Ice Age horse. This is one of the only areas in South America where such now-extinct species still existed when humans first arrived.

Solving the mystery

About 9,000 years ago, the climate shifted again, and desert conditions returned. Many of the lakes dried up and people moved on. An “archaeological silence” descended for the next 4,500 years, Grosjean said.

Grosjean noted that climatic conditions changed over several hundred years, so population declines were probably not catastrophic. “Over eight to 10 generations, population density adapts to available resources,” he said.

A few people apparently lingered near groundwater wells or lakebeds that retained enough moisture to support grazing areas for wildlife. Others may have migrated to the coast where marine resources remained rich.

Finally, around 4,500 years ago, the climatic pendulum swung once more toward favorable conditions, and Grosjean’s group found that humans reoccupied the wetland and cave sites. While the mountain lakes never returned to their earlier levels, people again camped along the modern shorelines. The archaeological silence was over, and thousands of years later, its mystery would be solved.