As the U.S. Navy tows its crippled destroyer, USS Cole, back toward safer harbors and Russia’s navy pulls the dead from the corpse of the attack submarine Kursk, some serious rethinking about the usefulness of these types of vessels should be under way. Unfortunately, the detective work in both fleets is more likely to produce scapegoats than an updated vision of naval warfare.

OFTEN IN the world of military planning, it takes a catastrophic failure of the old way of doing things to get new ideas some attention. It took Pearl Harbor in 1941 to convince the Navy that aircraft carriers, and not battleships, were their most important assets. It took the fall of Paris in 1940 to convince French generals that trenches and pillboxes were no defense from fast-moving armored forces. Time and again, military bureaucracies lag behind the curve, preferring to invest handsomely in the comfortable technologies of the last war instead of moving toward the future.

The Kursk was a nuclear-powered attack submarine designed to tail and sink the American fleet of the Cold War. The USS Cole is a destroyer designed primarily to safeguard the U.S. carrier fleet against Soviet attack. Both are impressive weapons, yet both are holdovers from another era pushed into duties (like patrolling the Persian Gulf alone) never envisioned for them. Thus, they are exposed to “low-tech” threats such as terrorists, and more sophisticated threats like the Chinese “Silkworm” missile (now in Iranian hands) they are not designed to handle.

SILVER LINING

The good news for Russia here is that Moscow has little money to produce more of these museum pieces. The Kursk and its 118 men probably went down in August because of poor maintenance. Before the ship sank, last January, the authoritative Jane’s defense unit noted that few of Russia’s nuclear-powered submarines were still operable: “Unless funding patterns change it is possible that the submarine missile force could either disappear or shrink to insignificance by the end of the decade.”

Ironically, Russia’s economic deficiencies will force its military to make the kind of tough decisions about hardware that the U.S. military successfully resists. With Russia’s military spending in a free fall, the luxury of keeping obsolete weapons systems afloat (or in the air or on the ground) can’t be tolerated. Behemoths like nuclear attack submarines ultimately may disappear from Russia’s Navy - hopefully in a more orderly fashion than the Kursk. They’ll still have outlived their mission - the Cold War - but at least they will go. In effect, Russia will cease to be capable of offensive operations, except in the most drastic, intercontinental ballistic meaning of the phrase.

GOLDEN OPPORTUNITY

Happily, for the U.S. military, there are choices. Unhappily, it looks as though American generals and admirals are determined to avoid the hard ones. They cry poor, but the American armed forces still spend as much on defense as their six nearest rivals combined. Thus, with the proper planning, there should be a way for the U.S. military to begin devoting more to the weapons of the future and less to the upkeep and purchase of weapons systems like the Cole, which essentially are products of the 1970s.

Taking the Navy as an example, however, there doesn’t seem to be much chance that true innovation will be the order of the day. The Navy has adjusted somewhat to the new realities of the world and plans to shrink slowly to a force of about 116 surface combatants - 11 carriers, plus assorted cruisers, destroyers, frigates and a handful of smaller ships. It also plans to reduce its present fleet of about 85 nuclear-attack subs to about 50. These decisions reflect the collapse of Soviet power, enormous leaps in technology in recent years, as well as smaller defense budgets.

SAILING RIGHT ALONG

Yet the four major Navy warship types now on order, which together eat up all of the Navy’s weapons procurement budget for the coming years, offer only incremental improvements on earlier designs. Indeed, the most dramatic move the Navy has taken in recent years is the cancellation in 1997 of a plan to produce an “arsenal ship,” an unglamorous, semi-submerged vessel packed with 500 Tomahawk cruise missiles and manned by a relatively small crew. “The arsenal ship was like an arrow shot at the heart of the carrier-borne Navy,” a senior officer at the Naval War College in Newport, R.I. told me “It probably could replace carriers in some roles, and it certainly was a lot cheaper.”

Here’s a quick look at what the Navy is building instead:

Seawolf: The most obvious boondoggle in the current batch is the Seawolf, an attack submarine - each costing $4.4 billion - offers on incremental improvements over the relatively new Los Angeles class sub it was designed to replace. In the early 1990s, before construction began, many inside the Navy and out believed the Seawolf should have been cancelled as the Soviet threat diminished. But the Navy’s submariners, aided by politicians with Seawolf money in their districts, managed to forestall the inevitable for years. Two of these fine but unnecessary subs are now in service, and the third and final ship, the USS Jimmy Carter, is being completed. The fact that only three will ever be built adds perhaps $1 billion a piece to their construction, since large projects like Seawolf rely on economies of scale to keep down costs.

New Attack Submarine : This smaller successor to the Seawolf at least offers features the Los Angeles class boats do not, including new Stealth hull materials. Still, at $2.2 billion each and given the lack of a credible rival abroad, defense experts and many inside the military would like to see the money spent on more ambitious leaps forward, at least as long as the potent Los Angeles class subs remain the best in the world.

CVX : On the ocean’s surface, aircraft carriers of the Nimitz-class, designed in the 1970s, continue to be the mainstay of the fleet, and the biggest ticket item in the Navy’s shipbuilding budget. Only one more of this class is being built: CVN-77, due to be delivered in 2003. The Navy plans to replace the Nimitz ships with a new class of carrier designated the CVX. Despite its “X” designation, the design now favored by the Navy is eerily similar to that of the Nimitz-class. Some early designs incorporated real innovation - a catamaran hull, for instance, to increase speed. But word is the Navy wants more of the same. It’s seeking $7 billion to get the first one in the fleet by 2007. Questions about their potential vulnerability to missiles or “low intensity” threats are routinely dismissed by senior Navy officers - in much the same way, I suppose, that the old battleship men of the 1930s laughed off the threat from the air.

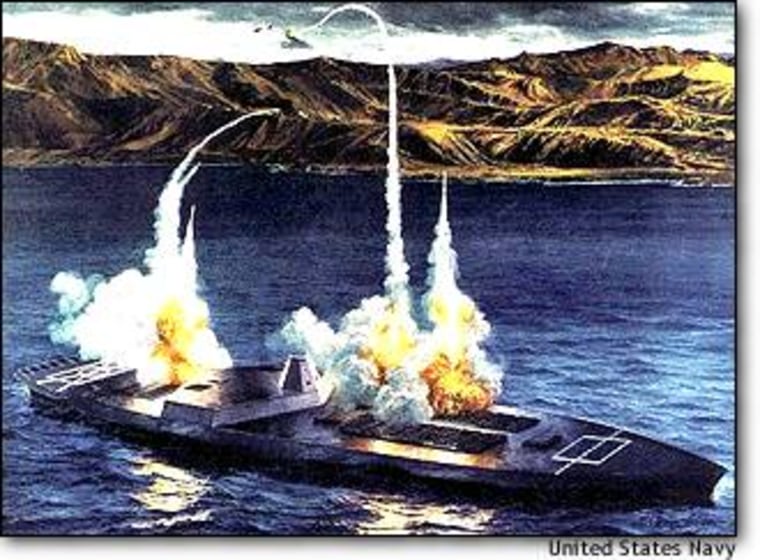

The DD-21 : The one naval program that seems to have grappled with the future is the DD-21, essentially a heavily armed destroyer that may serve some of the functions of the cancelled “arsenal ship.” In a rare example of sentimentalism losing out, the Navy says the DD-21 will replace all the various destroyers, cruisers and frigates currently in the fleet. In essence, those cruisers and frigates may disappear from the Navy once the lifespan of current vessels expires. The Navy is planning to build 32 of the DD-21 class, beginning in 2004. Two major innovations are planned: first, a lowered “profile,” making the SC-21s harder to target with radar; and second, a much smaller crew, down to about 90 from 200 on the older frigates (and as many as 400 on a cruiser).

These all are undeniably awesome ships on paper. Both the DD-21 and the CVX propose to use automation to cut down the size of the crews. Yet even these ships fall short of what would be possible with a more aggressive move into the future. The DD-21s, for instance, are billed as “land attack destroyers” because they’ll carry a store of Tomahawk cruise missiles. Yet they are a far cry from the arsenal ship concept. Indeed, had the arsenal ship been built, the need for the DD-21 class itself would be in question. What’s more, the near-sinking of the USS Cole last month raises real questions about the Navy’s ability to dramatically lower the sizes of the crews on these DD-21s. No automation yet developed can replace a the kind of human inspections that should always be standard operating procedure when small boats approach a Navy vessel in a foreign port.

For a fraction of the cost of a Seawolf submarine, the Navy could park an arsenal ship off the Korean peninsula and another in the Arabian Sea, obviating the need to put thousands of Americans on carriers and their escort ships in the line of fire. Of course, carriers will still be needed for missions where “targets of opportunity” are important. But arsenal ships could take the strain off the Navy, which currently cycles aircraft carriers in and out of places like the South China Sea and Persian Gulf at enormous cost - both financial and in terms of retention. The estimated cost of the arsenal ship was $800 million per vessel, a price many thing was way too low. But even if you double it, one cancelled Seawolf would have purchased three of them.

The problem for the Navy, of course, is no so much that the arsenal ship was a bad idea. Rather, the arsenal ship looked an awful lot like a weapon that could make it harder to build dozens of new cruisers, destroyers and carriers. And that’s a bit too much progress to swallow.

Michael Moran is senior producer for special reports at MSNBC.com