The Milky Way may look like a giant spiral in space, but in the world of invisible dark matter our galaxy is shaped like a giant, flattened beach ball, a new study has found.

The universe is thought to be made up of mostly dark matter, a mysterious substance that does not reflect light, so is invisible. Scientists cannot detect it directly; the only way they know it's there is by measuring its gravitational tug on regular matter.

Over 70 percent of the mass of most galaxies, including the Milky Way, is thought to be made up of this elusive material. Dark matter seems to shroud the remaining visible matter in giant spheres called haloes.

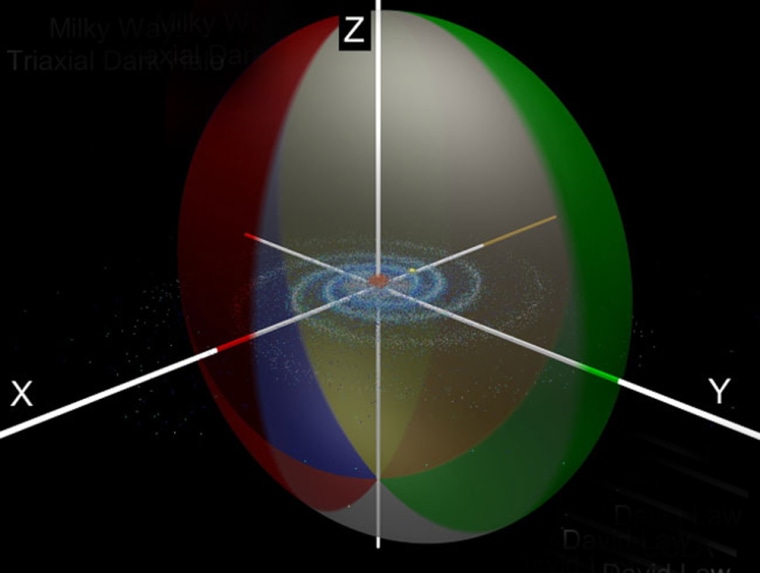

But the new study found that the Milky Way's halo isn't exactly spherical, but squished. In fact, its beach-ball form is flattened in a surprising direction — perpendicular to the galaxy's visible, pancake-shaped spiral disk.

"We expected some amount of flattening based on the predictions of the best dark matter theories," said researcher David Law of UCLA. "But the extent, and particularly the orientation, of the flattening was quite unexpected. We're pretty excited about this, because it begs the question of how our galaxy formed in its present orientation."

Law, along with co-researchers Steven Majewski of the University of Virginia and Kathryn Johnston of Columbia University, announced the findings here today at the 215th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Washington, D.C.

The research is the first time scientists have measured the three-dimensional shape of a dark matter halo. They traced it by measuring its effect on the small dwarf satellites that orbit around the Milky Way. These are like miniature galaxies, with only a fraction of the number of the stars a full-fledged galaxy contains.

Though the mini-galaxies orbit too slowly to watch their movement in real time, astronomers can deduce their velocities by observing how some stars are torn from them by tidal forces, leaving a trace of the galaxy's motion like breadcrumbs along a path.

The scientists used measurements of the Sagittarius Dwarf Galaxy, one of the largest of the small galaxies circling the Milky Way. For a long time, no one had been able to understand the orbit of this dwarf: Different parts of its path suggested different overall journeys.

Recently, the researchers finally made sense of Sagittarius' behavior by assuming that the Milky Way's dark matter halo has a different length in each of the three dimensions of space.

"At last we have a way of explaining what previously seemed like conflicting information about the Sagittarius system," Majewski said.