Mercury is wracked by intense magnetic disturbances more extreme than any on Earth, new research suggests.

The small, rocky planet also experienced volcanic activity for much longer than once thought, according to several new studies based on observations during the latest flyby of the small, rocky planet by a NASA spacecraft.

The new findings come from data collected by NASA's MESSENGER spacecraft, which unearthed even more secrets about the closest planet to the sun during its third and last flyby of Mercury last September. To start, the probe discovered Mercury's magnetic field, or "magnetosphere," apparently releases energy in violent magnetic disturbances called substorms far more extreme than comparable ones seen on Earth, which include spikes in the size and intensity here of colorful auroras and the outermost Van Allen radiation belt.

NASA launched MESSENGER in 2004 and it zoomed within 142 miles (229 km) of its Mercury's surface during its most recent flyby. The craft, destined to orbit around the planet in 2011, has already yielded a trove of knowledge, solving mysteries such as whether it had volcanoes. [Top 10 Mercury Mysteries]

The scientists detailed their new findings in three papers appearing online July 15 in the journal Science.

Mercury's powerful tail

In one study, researchers scrutinized MESSENGER's observations of Mercury's magnetosphere as the planet was barraged by the solar wind. They found in the magnetosphere's tail — the "magnetotail" — the magnetic field could rise and fall in strength by a factor of two to 3.5 in just two to three minutes.

Magnetospheric physicist James Slavin at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and his colleagues suggest the rapid buildup and release of energy seen there are much like substorms on Earth, but ours accrue 10 times less energy and take place over the course of an hour or so.

"We weren't anticipating anything this strong," Slavin told SPACE.com. "On Mercury, unlike Earth, there's not really an electrically conducting ionosphere layer in the atmosphere to limit the electric field imposed by the solar wind, and Mercury's proximity to the sun probably pumps in a lot more energy as well."

On Earth, such magnetic storms interact with the atmosphere and produce the Northern Lights.

Volcanoes on Mercury

In another study, the MESSENGER craft found that volcanic activity on Mercury may have lasted far longer than researchers previously thought.

"It changes a lot of our preconceived notions about how Mercury might have evolved," planetary scientist Louise Prockter at Johns Hopkins University told SPACE.com.

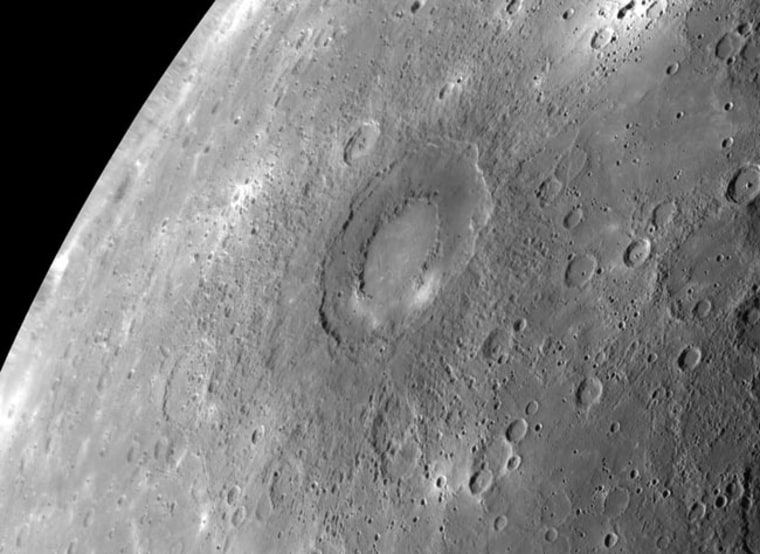

Prockter and her colleagues analyzed images sent back from MESSENGER of a 180-mile (290-km) impact basin on the planet's surface. This basin, named after the famed composer Rachmaninoff, is among the youngest to be observed on the planet and has exceptionally smooth plains seemingly made of volcanic material that once flowed across the basin's floor.

The fact these plains are sparsely cratered — as opposed to littered with evidence of meteoric impacts on Mercury over the years — suggest the volcanism that created the plains must have been fairly recent. The researchers also discovered a depression northeast of the basin surrounded by a halo of bright deposits, which they propose to be the largest volcanic vent identified on Mercury so far.

In light of these findings, Prockter and her colleagues propose that volcanic activity on Mercury was not only pervasive early in the planet's history, but also lasted up to 2 billion years longer that thought. Under that proposal, activity would have been under way as recently as 1 to 2 billion years ago.

"Until MESSENGER, we had expected Mercury to get rid of all its heat early on in its history because it's pretty small," Prockter said. "We'll want to see if the volcanism we see with this basin was an isolated case or whether it was widespread across the surface, which would have us perhaps rethinking our models of Mercury. It seems that Mercury did not get rid of her heat nearly as efficiently as had previously been thought."

Wispy atmosphere

Scientists also found that the very tenuous atmosphere of Mercury, or "exosphere," made of elements such as magnesium, calcium, and sodium, is apparently created and maintained by a number of different processes, such as the forces generated by the planet's magnetic field. These findings help shed light on the composition of Mercury's surface and how matter is moved over the planet.

These new findings are whetting the appetites of scientists for when MESSENGER gets into orbit around Mercury.

"It's certainly surprised me that we learned so much just from flyby data," Prockter said. "Once we're in orbit, we're going to learn so much more. We've just scratched the surface — Mercury is even more surprising and interesting than we thought, and will no doubt continue to be so."