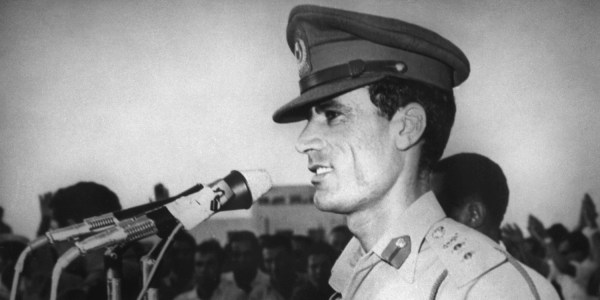

After 42 years of absolute power in Libya, Col. Muammar el-Qaddafi spent his last days hovering between defiance and delusion, surviving on rice and pasta his guards scrounged from the emptied civilian houses he moved between every few days, according to a senior security official captured with him.

Under siege by the former rebels for weeks, Colonel Qaddafi grew impatient with life on the run in the city of Surt, said the official, Mansour Dhao Ibrahim, the leader of the feared People’s Guard, a network of loyalists, volunteers and informants. “He would say: ‘Why is there no electricity? Why is there no water?’ ”

Mr. Dhao, who stayed close to Colonel Qaddafi throughout the siege, said that he and other aides repeatedly counseled the colonel to leave power or the country, but that the colonel and one of his sons, Muatassim, would not even consider the option.

Still, though some of the colonel’s supporters portrayed him as bellicose to the end and armed at the front lines, he actually did not take part in the fighting, Mr. Dhao said, instead preferring to read or make calls on his satellite phone. “I’m sure not a single shot was fired,” he said.

As Libya’s interim leaders prepared Saturday to formally start the transition to an elected government and set a timeline for national elections in 2012, sweeping away Colonel Qaddafi’s dictatorship, they faced the certainty that even in death the colonel had hurt them. The battle for Surt, Colonel Qaddafi’s birthplace, was prolonged for months by the presence of the fiercely loyal cadre he kept with him, delaying the end of a war most Libyans had hoped would be over with the fall of Tripoli in August.

Mr. Dhao’s comments, in an interview on Saturday at the military intelligence headquarters in Misurata, came as the final details of the colonel’s death, at the hands of the fighters who had captured him, were still being debated.

Residents of Misurata spent a third day viewing the bodies of Colonel Qaddafi and his son at a meat locker in a local shopping mall. Officials with the interim government have said that they will conduct an autopsy on the bodies and investigate allegations that the two men may have been killed while in custody, though local security officials have said they see no need for such an inquiry.

Mr. Dhao, who is said to be a cousin of Colonel Qaddafi, became a trusted member of his inner circle. As head of the People’s Guard, he presided over a force accused of playing a central role in the violent crackdowns on protesters during the uprising, including firing on unarmed demonstrators in Tripoli’s Tajura neighborhood. The guard’s volunteer members harassed residents at checkpoints throughout the city. Mr. Dhao was believed to have kept weapons and detainees at his farm, according to Salah Marghani of the Libyan Human Rights Group.

In a separate interview with Human Rights Watch, Mr. Dhao denied that he had ordered any violence.

On Saturday, he spoke in a large conference room that served as his cell, wearing a blanket on his legs and a blue shirt, maybe an electric company uniform, inscribed with the word “power.”

A few guards were present, but they spoke only among themselves. He said his captors had treated him well and had sent doctors to tend to injuries he sustained before his capture, including shrapnel wounds under his eye, and on his back and left arm.

Many of his statements appeared to be self-serving; he said, for instance, that he and others had repeatedly tried to convince Colonel Qaddafi that the revolutionaries were not rats and mercenaries, as the colonel was fond of saying, but ordinary people.

“He knew that these were Libyans who were revolting,” he said. Other times, he seemed full of regret, explaining his failure to surrender or escape as his way of fulfilling “a moral obligation to stay” with the colonel before adding, “My courage failed me.”

His account of the battle did not address the accusations made by the former rebels of abuses by loyalist forces inside Surt. Ismael al-Shukri, the deputy chief of military intelligence in Misurata, said that loyalists had used families as human shields and that there were reports that loyalist soldiers had detained daughters to prevent families from leaving. The former rebels have also said that the Qaddafi forces executed soldiers who refused to fight.

Colonel Qaddafi fled to Surt on Aug. 21, the day Tripoli fell, in a small convoy that traveled through the loyalist bastions of Tarhuna and Bani Walid. “He was very afraid of NATO,” said Mr. Dhao, who joined him about a week later.

The decision to stay in Surt was Muatassim’s; the colonel’s son reasoned that the city, long known as an important pro-Qaddafi stronghold and under frequent bombardment by NATO airstrikes, was the last place anyone would look.

The colonel traveled with about 10 people, including close aides and guards. Muatassim, who commanded the loyalist forces, traveled separately from his father, fearing that his own satellite phone was being tracked.

Apart from a phone, which the colonel used to make frequent statements to a Syrian television station that became his official outlet, Colonel Qaddafi was largely “cut off from the world,” Mr. Dhao said. He did not have a computer, and in any case, there was rarely any electricity. The colonel, who was fond of framing the revolution as a religious war between devout Muslims and the rebel’s Western backers, spent his time reading the Koran, Mr. Dhao said.

Slideshow 34 photos

Moammar Gadhafi

He refused to hear pleas to give up power. He would say, according to Mr. Dhao: “This is my country. I handed over power in 1977,” referring to his oft-repeated assertion that power was actually in the hands of the Libyan people. “We tried for a time, and then the door was shut,” the aide said, adding that the colonel seemed more open to the idea of giving up power than his sons did.

For weeks, the former rebels fired heavy weapons indiscriminately at the city. “Random shelling was everywhere,” said Mr. Dhao, adding that a rocket or a mortar shell struck one of the houses where the colonel was staying, wounding three of his guards. A chef who was traveling with the group was also hurt, so everyone started cooking, Mr. Dhao said.

About two weeks ago, as the former rebels stormed the city center, the colonel and his sons were trapped shuttling between two houses in a residential area called District No. 2. They were surrounded by hundreds of former rebels, firing at the area with heavy machine guns, rockets and mortars. “The only decision was whether to live or to die,” Mr. Dhao said. Colonel Qaddafi decided it was time to leave, and planned to flee to one of his houses nearby, where he had been born.

On Thursday, a convoy of more than 40 cars was supposed to leave at about around 3 a.m., but disorganization by the loyalist volunteers delayed the departure until 8 a.m. In a Toyota Land Cruiser, Colonel Qaddafi traveled with his chief of security, a relative, the driver and Mr. Dhao. The colonel did not say much during the drive.

NATO warplanes and former rebel fighters found them half an hour after they left. When a missile struck near the car, the airbags deployed, said Mr. Dhao, who was hit by shrapnel in the strike. He said he tried to escape with Colonel Qaddafi and other men, walking first to a farm, then to the main road, toward some drainage pipes. “The shelling was constant,” Mr. Dhao said, adding that he was struck by shrapnel again and fell unconscious. When he woke up, he was in the hospital.

“I’m sorry for all that happened to Libya,” he said, “from the beginning to the end.”

Suliman Alzway contributed reporting.

This article, "," first appeared in The New York Times.