Frontier settlers, who "live on the edge," may be more likely to have larger families than those who stay snuggled at the core of a settlement, based on new research of how the French settled Quebec centuries ago.

A study of Quebecois records determined that the women among the families at the outskirts of the population were about 15 percent more fertile than those who lived in more-established settlements, and consequently their families contributed much more to Quebec's modern gene pool.

From their findings, researchers speculated that improved fertility after successful colonization in rural areas could have played a major role in the spread of the human population from Africa 50,000 years ago.

"We find that families who are at the forefront of a range expansion into new territories had greater reproductive success. In other words, that they had more children, and more children who also had children," study researcher Damian Labuda of the University of Montreal in Quebec explained in a statement. "As a result, these families made a higher genetic contribution to the contemporary population than those who remained behind."

Pioneering Quebecois

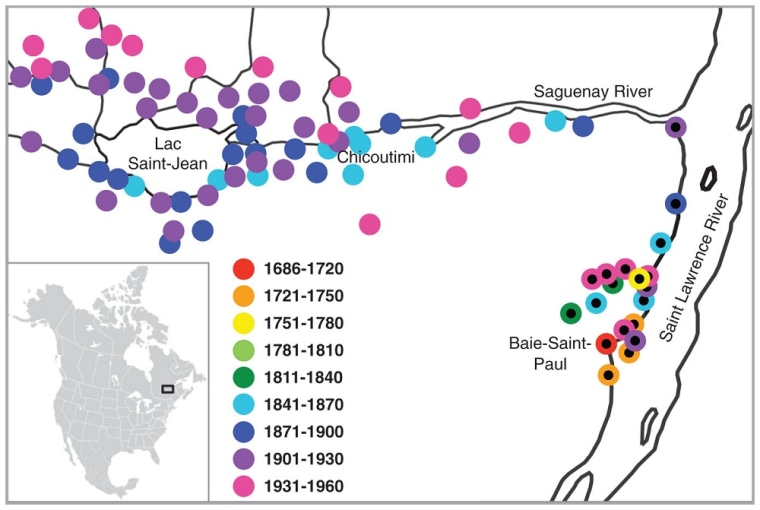

The researchers studied the records of 1.2 million Quebecois who lived between 1686 and 1960 in the area between the St. Laurent River and Lac Saint-Jean. These records were reconstructed from church registries and turned into genealogies of who settled where, when they married and how many children they had as the population wave front continued to change.

The team found that those who settled on the fringes of existing settlements — the so-called "wave front" of the movement into rural, unsettled areas — married at younger ages, had more children and grandchildren, and passed on more of their genes to modern Quebecois than those who lived near the older, previously established settlements.

The women of the population's outskirts bore an average of nine children, while the women who lived in the core of the population had about eight. The genetic dominance of these frontier women came from several sources: The women tended to marry about a year sooner, and their children were more likely to marry and to have higher fertility rates themselves.

Because they were more fertile, these wave-front families left more genes in the modern population — some 1.2 to 3.9 times more genes than those families living in core, populated areas at the time. The number differs by how many generations ago the ancestors lived. The older the generation, the more it contributed to the gene pool.

Population expansion

The children of these frontier women had better access to potential mates, the researchers found, probably because there was less competition with other women and they had more land to inhabit and farm, which means more resources available to them — a factor that can boost health and fertility. This is similar to what other researchers saw when studying the French population that originally founded Quebec.

Since these early settlers played such an important role in the genetics of future populations, any genetic traits they had would be passed on and well represented, as the researchers saw in their study.

"Theory predicts that traits related to dispersal and reproduction should be evolving during range expansions. We have only been able to measure differences in fertility or fitness between the front and the range core, but other traits might have evolved," study researcher Laurent Excoffier of the University of Montreal and the University of Berne in Switzerland told LiveScience in an email. "Unfortunately, we do not have records of what these could be."

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter and on .