Russia’s troubled Phobos-Grunt spacecraft, which is stuck in low-Earth orbit due to an engine failure rather than on its way to Mars, appears to be doomed, with small pieces of the wayward probe already falling to Earth.

Flotsam from the stranded Mars spacecraft quickly re-entered Earth’s atmosphere and were reportedly listed in the space object catalog maintained by the United States Strategic Command.

According to Space.com sources, shedding of pieces from spacecraft and rocket bodies at such a low altitude is common. But since the altitude of Phobos-Grunt itself did not change after the two small objects fell from the vehicle, the fragments were likely not that significant.

Still, the news is not good for Phobos-Grunt. According to one analyst, "(T)he vehicle appears dead in the water."

A fiery demise

Phobos-Grunt was launched Nov. 8 on a mission to collect rock samples from the Mars moon Phobos. Shortly after launch, the spacecraft suffered a malfunction that stranded it in Earth orbit.

Despite repeated attempts, mission controllers have not been able to communicate with Phobos-Grunt.

Unless engineers can regain control of the spacecraft, the 14.6-ton (13.2 metric tons) probe is headed for an uncontrolled plunge into Earth’s atmosphere.

"I estimate that Phobos-Grunt will decay on Jan. 13, 2012, plus or minus eight days," said Ted Molczan of Toronto, a leader in the community of citizen satellite watchers.

After picking up a signal from the marooned probe Nov. 23 at a ground station in Australia, the European Space Agency (ESA) had been tracking Phobos-Grunt as part of a joint effort with the Russian Federal Space Agency.

Last week, however, ESA announced that, "in consultation and agreement with Phobos-Grunt mission managers" in Russia, they would end tracking support.

"Efforts in the past week to send commands to and receive data from the Russian Mars mission via ESA ground stations have not succeeded; no response has been seen from the satellite. ESA teams remain available to assist the Phobos-Grunt mission if indicated by any change in the situation," agency officials said in a statement.

Lessons learned from Phobos-Grunt

There have been a number of lessons learned in trying to rescue Phobos-Grunt, said Wolfgang Hell, a service manager who is overseeing ESA support to Russia's main contractor on the Phobos-Grunt project. Hell is based at the European Space Operations Center in Darmstadt, Germany.

In a Space.com interview late last month, Hell said there were challenges beyond what ESA does in support of NASA missions. For one, NASA and ESA spacecraft are designed with interoperability in mind to make joint missions a relatively straightforward process, he advised.

"That was not the case with this (Phobos-Grunt) mission. The uplink is completely private in terms of data structures and telecommand protocol," Hell said.

Also, early ideas about how to rescue Phobos-Grunt could have benefited from better knowledge of the true condition of the spacecraft.

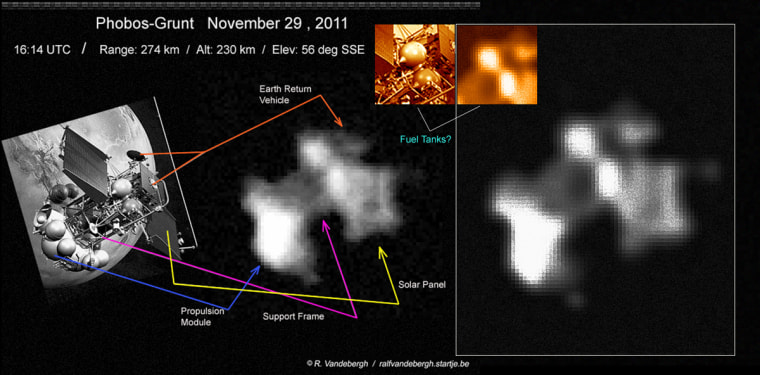

"Maybe even imaging capabilities would have been useful," he said. "We were not absolutely certain that the solar arrays were deployed … although I believe the Russians got telemetry initially stating that. But an optical verification that this is true would be nice."

Re-entering Earth's atmosphere

Given the growing prospect that the sizable Phobos-Grunt will face an uncontrolled re-entry, there will undoubtedly be pieces of the spacecraft that survive, analysts agree.

For one, Phobos-Grunt’s nose-cone-shaped descent vehicle — designed to bring back to Earth bits and pieces of Phobos, one of the two moons of Mars — was purposely fabricated to fall to Earth and land without the use of a parachute.

Also onboard Phobos-Grunt, and facing destruction, is the hitchhiking Chinese Mars orbiter, Yinghuo-1.

Due to the spacecraft’s hefty load of toxic fuels, some concern has been raised about the probe’s re-entry and the prospect that dangerous propellant could reach the Earth’s surface.

Don’t lose sleep

This concern has been addressed by Nicholas Johnson, NASA’s chief scientist for orbital debris at the Johnson Space Center in Houston.

Johnson spoke to the issue Monday on "The Space Show," a popular radio and Internet program hosted by David Livingston. The orbital debris expert said that the head of the Russian space agency has explicitly said that the main propellant tanks for Phobos-Grunt are made of aluminum.

"Aluminum has a much lower melting temperature," Johnson said. "So with the statement by the Russians that the main propellant tanks are aluminum, that certainly would significantly reduce the chances of any harmful substance reaching the surface of the Earth."

Still, there is no reason to panic, Johnson said, because the Earth is roughly three-fourths water, and another large percentage of the land is relatively sparsely populated.

"I’m happy to report, since the beginning of the Space Age, there’s been no report of anybody being harmed … by being hit by space debris re-entering."

On average, there is one known cataloged object that falls back to Earth every day, Johnson added.

"This is not a serious concern," he said. "I certainly wouldn't lose any sleep over it."

Leonard David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades. He is a winner of this year's National Space Club Press Award and a past editor-in-chief of the National Space Society's Ad Astra and Space World magazines. He has written for Space.com since 1999.