Dick Cheney has redesigned the vice presidency into one of the most powerful offices in Washington.

But the pre-Cheney tradition was for the vice president to be an unobtrusive understudy whose job was to give speeches supporting the president and to break ties in the Senate on the rare occasions when it was necessary.

Being a candidate for vice president was often a ticket to obscurity — who remembers Charles G. Dawes, John Sparkman or James Stockdale?

Even if the ticket wins and the candidate becomes vice president, the post may do more harm than good to his future since it requires him to subordinate his identity to that of the president, as happened to Richard Nixon when he served under Dwight Eisenhower.

In 1976, when Walter Mondale ran as Jimmy Carter’s vice presidential choice, former Sen. Eugene McCarthy dismissed him with the put-down: “Mondale has the soul of a vice president.”

And when Senate Minority Leader Bob Dole was battling Vice President George Bush for the 1988 GOP presidential nomination, Dole mocked Bush by saying that being vice president “is indoor work and no heavylifting. ... You don't make decisions.”

Despite the vice presidency’s lack of power — again Cheney being the anomaly — a presidential candidate’s choice of a running mate can be perilous.

A running mate who is dogged by questions about his financial dealings or who makes jarring comments on the campaign trail can be a fearsome distraction for a presidential candidate.

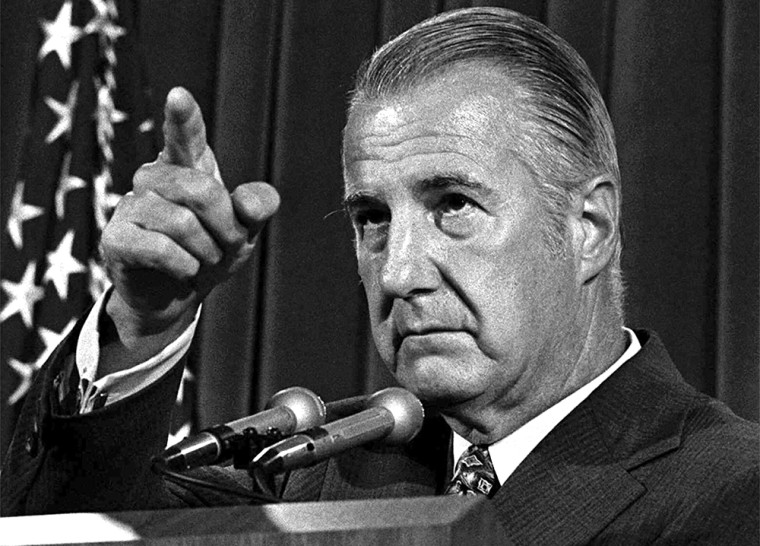

In 1968, Maryland Gov. Spiro Agnew, whom Nixon chose as his running mate in an appeal to the Border and Southern states, displayed a penchant for unscripted mayhem.

After calling Polish-Americans “Polacks,” Agnew referred to a Japanese-American reporter covering his campaign as "the fat Jap." A while later, by one campaign historian’s account, “Agnew almost lost the election for Nixon” by charging that Democratic candidate Hubert Humphrey was “squishy-soft on Communism.”

What is startling by today’s standards is how casual the selection of a running mate once was. Nixon apparently had only talked to Agnew a few times before picking him.

In 1944, when Democratic Party leaders pressured Franklin Roosevelt to jettison Vice President Henry Wallace, Roosevelt considered several replacements including Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas. Party bosses wanted FDR to pick Missouri Sen. Harry Truman.

FDR, who often played poker with Douglas but barely knew Truman, dashed off a note to Democratic National Committee chairman Robert Hannegan, telling him, “I should, of course, be very glad to run with either of them (Douglas or Truman) and believe that either one of them would bring real strength to the ticket.”

The party bosses prevailed and Truman it was. His vice presidency lasted less than three months as Roosevelt’s death made him president.

Eagleton as turning point

The case of 1972 Democratic vice presidential candidate Thomas Eagleton was a turning point in the selection process.

Presidential nominee George McGovern asked a number of party luminaries, including Sen. Edward Kennedy, to run with him. After each of them rejected his offer, McGovern turned to Eagleton, whom he did not know well.

The disclosure of Eagleton’s psychiatric and electroshock treatment forced him off the ticket and doomed McGovern’s already ill-starred presidential bid.

Since Eagleton, thorough vetting of any potential running mate has been the rule. Guiding the candidate as he selects a running mate are several factors:

- A need to appeal to a constituency within the party: When Mondale picked Geraldine Ferraro in 1984, he was attempting to vitalize the Democrats’ appeal to women voters. In 1952, when Eisenhower put Nixon on his ticket, he was wooing the hard-line anti-Communist wing of the Republican Party. Nixon had played a big role in investigating alleged spying by former State Department official Alger Hiss.

- An attempt to shore up support in a particular region of the country: Democratic presidential candidates who are Northerners often pick a Southerner to balance the ticket. Texans have frequently been the choice, as in 1932 when Roosevelt picked John Nance Garner as his veep; 1960, when John Kennedy chose Lyndon Johnson; and, 1988, when Michael Dukakis tapped Lloyd Bentsen.

- Ideological and “image” balance. Gore’s choice of Sen. Joe Lieberman four years ago had something to do with Lieberman’s Senate speech criticizing President Clinton’s behavior in the Monica Lewinsky scandal.

Despite the cases of Agnew in 1968 and Eagleton in 1972, it is hard to prove from the record since then that a misguided choice has cost a candidate the White House.

A Quayle effect?

As jittery and callow as Dan Quayle seemed to some viewers of his 1988 debate with Bentsen, he did not stop Bush from easily beating Dukakis that November.

The best that John Kerry can aim for as he makes his choice of a running mate is someone who might pull in a marginal state or two for the Democratic ticket and who can stir excitement among the electorate.

Ticket-balancing in the traditional sense of a Northerner picking a Southerner is part of what Democratic campaign consultant Chris Kofinis calls the “science” of vice presidential selection.

But, Kofinis adds, “There is also an art to deciding who is the best V.P. Presidential elections are inevitably a battle of fostering positive perceptions and creating winning images. Selecting the best vice president is also about creating this winning image for voters. Kerry's vice president will be one of the most important examples — if not the most important example —with which to create this winning image.”

The unconventionality of Clinton’s choice of Al Gore, a relatively young man like himself, from a state that bordered his own, is what got the attention of the news media and the electorate and helped Clinton win the White House.