A study of Greenland's rocks may have turned up something unexpected: the oldest and largest meteorite crater ever found on Earth.

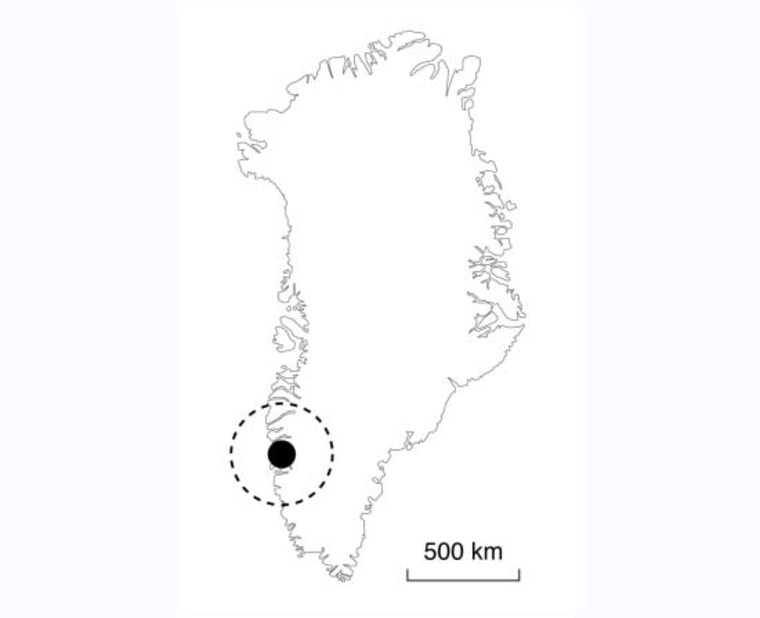

Researchers think the crater was formed 3 billion years ago, making it the oldest ever found, said Danish researcher Adam Garde. The impact crater currently measures about 62 miles (100 kilometers) from one side to another. But before it eroded, it was likely more than 310 miles (500 kilometers) wide, which would make it the biggest on Earth, Garde told OurAmazingPlanet.

The team has calculated it was caused by a meteorite 19 miles (30 kilometers) wide — which, if it hit Earth today, would wipe out all higher life.

Mystery feature

In the 3 billion years since impact, the land has been eroded down to about 16 miles (25 kilometers) below the original surface. But the effects of the intense shock wave and heat penetrated deep into Earth and remain visible today, said Garde, a researcher at the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland. [Meteor Mania: How Well Do You Know 'Shooting Stars'?]

Garde had been conducting research on Greenland's geology and noticed several strange features that didn't make sense. One day in September 2009, he came up with the extreme explanation of an impact from a meteorite. His team collected samples over the years and published the results in the July issue of Earth and Planetary Science Letters. He's now "100 percent positive" it's a crater, for several reasons, he said.

For one, he found widespread crushed rocks in a circular shape that seemed to be caused by the shock waves of a massive impact. Second, there are deposits of a melted mineral called K-feldspar (or potassium-feldspar) that could have been liquefied only at extremely high heat, like that caused by an meteorite's crash landing. There's also widespread evidence of weathering by hot water, which he thinks was caused by the ocean rushing into the crater after it struck the area. The area may have been covered by a shallow ocean at the time, but even if it wasn't, it doesn't matter, Garde said. "The crater from a meteorite that big would have caused the sea to rush in," he said.

Mining for minerals

John Spray, a meteorite expert at the University of New Brunswick who wasn't involved in the research, said he thinks it's probably a meteor crater, but points out that the case hasn't been proven and may not be for some time.

"It's very interesting and it's good science," he said. "But we don't really know how to recognize very old impact craters, because they are typically so highly modified."

That's because Earth is alive and constantly changing, due to processes such as erosion, precipitation and plate tectonics. At one time, Earth probably had as many craters as the moon, which is essentially geologically dead. But these have mostly been wiped away, destroyed by erosion and the like.

Only around 180 impact craters have ever been discovered on Earth, and nearly one-third of them contain significant minerals deposits such as precious metals. A Canadian mining company, North American Nickel, is exploring the region where the potentially newfound crater is, looking for nickel and other mineral deposits, company geologist John Roozendaal said. They are conducting airborne surveys and will soon do more mapping, small-scale sampling and drilling to see if they can find an area that could be economical to mine.

These impacts are of interest to mining companies not because of the large meteorites themselves — they typically vaporize — but because of the effect upon the Earth's surface. The impact heats rocks so much that metals can melt and then collect toward the bottom of the crater. Craters can also be important sources of oil and gas; the crushed, permeable rocks can act like a sponge, absorbing hydrocarbons.

Before this discovery, the oldest crater was thought to be the Vredefort crater in South Africa, estimated to be 2 billion years old. At 186 miles (300 kilometers) wide, it's also the largest crater that remains visible. Scientists expect that there were many more craters formed around 3-4 billion years ago when Earth lacked a protective atmosphere.

Garde said the most interesting thing about the experience was finding an alternate explanation for something outside of his training. "I had a problem I couldn't solve in a region I knew very well," he said. "A meteor impact was the idea that made everything fall into place — It's not something I was looking for."

Reach Douglas Main at . Follow him on Twitter . Follow OurAmazingPlanet on Twitter . We're also on and .