Big-time sports seem to have a habit of fumbling the ball.

While the sight of multimillionaire baseball players dressed up in their Sunday best and quivering under the questioning of a congressional committee about the illicit use of anabolic steroids was striking, it was by no means the worst episode in a century of scandals that at times have seriously called into question the worthiness of a sport or even of organized athletics itself.

The most infamous scandal tainted that most American of institutions, the World Series.

In 1919, the Chicago White Sox were the best team in baseball and were widely expected to beat the Cincinnati Reds. But when it turned out that unexpectedly heavy bets had been placed on the Reds, and then when the Reds won five games to three (the series was nine games back then) — suspicions began to form.

Eventually, eight Chicago players were accused of throwing the series, including Shoeless Joe Jackson, who is still regarded as one of the finest players the game ever produced. Damage to baseball's image was so severe that shaken team owners hired U.S. District Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis as the first sports commissioner.

Landis used his absolute powers to ban the eight “Black Sox” from baseball for life, upholding his decision even after seven of the eight were acquitted of fraud and the eighth was never tried.

Lore has it that at Jackson’s trial, a young boy tugged on his arm and pleaded, “Say it ain’t so, Joe.” What he actually said, according to the day’s report in the Chicago Herald and Examiner, was “It ain’t true, is it?”

To which Jackson — whom many baseball historians have championed as blameless — replied, “Yes, kid, I’m afraid it is.”

Ohio State Blackeye

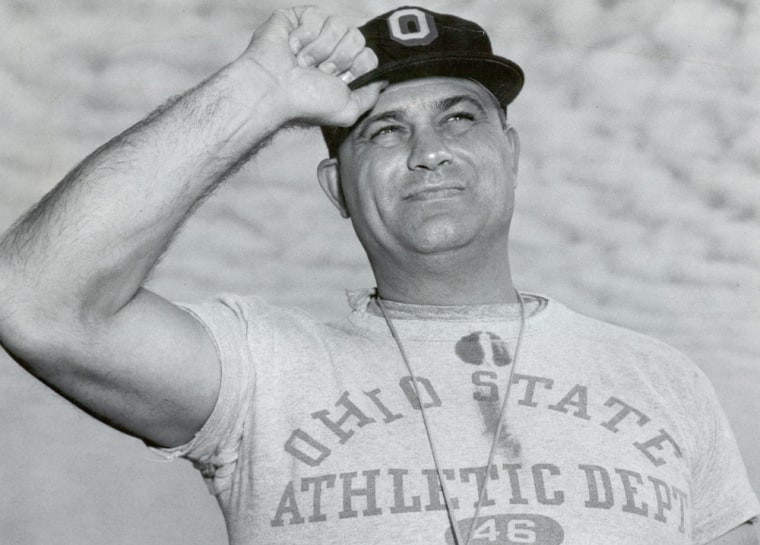

Woody Hayes was as fearsome a coach as ever stalked a college football sideline. Educated as a historian, he mined the past for examples of excellence he could teach his players.

Some of those examples were not the gentlest of characters — Gen. George C. Patton was a particular favorite — and long before his Ohio State Buckeyes had won the last of his three national championships, Hayes had become a polarizing figure for his bellowing tantrums during games and practices.

The 1978 Gator Bowl, in Jacksonville, Fla., was Hayes’ last game. He was fired a day after television cameras recorded him punching a Clemson University linebacker, Charlie Baumann, in the throat after Baumann intercepted a pass to seal Clemson’s 17-15 victory.

Slam dunk

Less than a year after it won both the 1950 National Collegiate Athletic Association championship and the National Invitation Tournament — a double never duplicated before or since — City College of New York was disgraced when three of its players were arrested on bribery charges. They were accused of “shaving” points — intentionally winning games by less than they were expected to, so gamblers could collect on their failure to cover the spread.

By the time the investigation was at full steam, a half-dozen other schools were implicated in the scandal, including the powerhouse University of Kentucky. The Wildcats’ program was suspended for the entire 1952-53 season, and the National Basketball Association banned three of its players for three seasons.

A losing bet

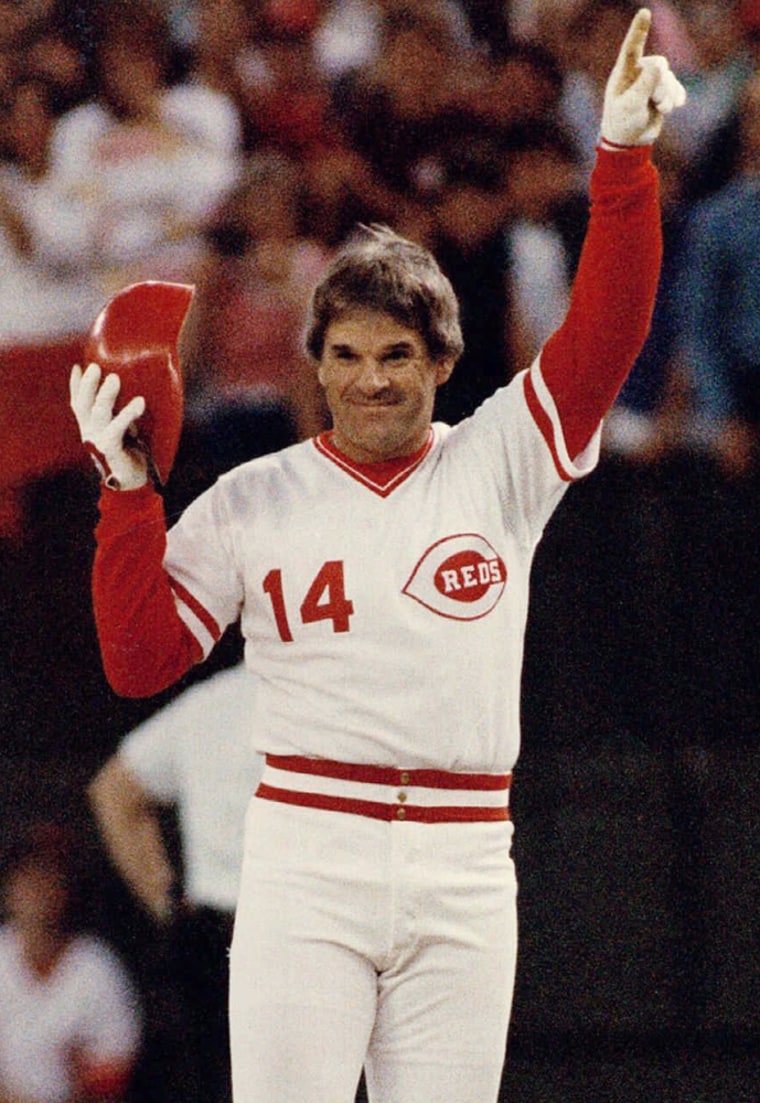

Pete Rose, statistically the greatest hitter in baseball history, was banned for life for betting on games in 1989, followed by a five-month prison sentence for tax evasion.

For 14 years, Rose insisted that he never gambled on baseball, and sportswriters slowly came around to his side. By last year, a significant number of influential people in the game were calling for his reinstatement and election to the Hall of Fame.

Then Rose wrote “My Prison Without Bars,” an autobiography that revealed that he had been lying for all those years. He admitted that he had, indeed, wagered on games while managing the Cincinnati Reds throughout the 1980s. Left with egg on their faces, Rose’s champions walked away, calling him a “pathological liar” and a “circus act.” Major League Baseball has not acted on his request for reinstatement after eight years.

Hold that (betting) line

Pro football had its own gambling scandal in 1963, when all-stars Alex Karras, the fearsome defensive lineman for the Detroit Lions, and Paul Hornung, the Green Bay Packers running back who still holds the record for points scored in a season, were suspended for a year for betting on games and associating with known gamblers.

They were two of the most colorful figures in football.

Hornung, the Heisman Trophy-winning “Golden Boy” from Notre Dame, returned in 1964 and went on to win two more National Football League championships with the Packers.

Karras, the prototype of today’s unstoppable pass rusher even though he was so nearsighted that he couldn’t see who was trying to block him, spent the year off as a pro wrestler. He eventually went on to a long acting career, standing out as the horse-punching Mongo in “Blazing Saddles” and the gentle George Papadapolis in the sit-com “Webster.”

Karras has yet to be enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame, for reasons no one can really figure. His contemporaries and football historians agree that he was one of the greatest defenders to play the game, but the Hall has never opened its doors. It can’t be because of the gambling suspension: Hornung was inducted in 1986.

Chipped ice

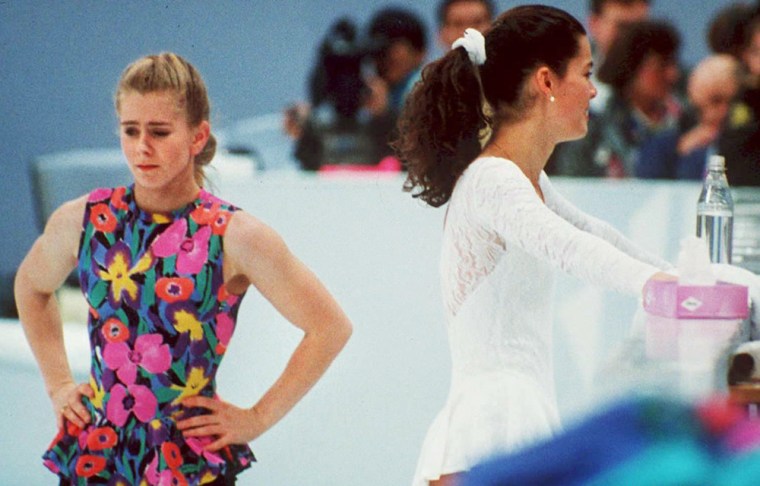

The women’s figure skating competition at the 1994 Winter Olympic Games was overshadowed by the rivalry between two of the top American skaters, Nancy Kerrigan and Tonya Harding. Harding, the U.S. champion, was on the team only because she sued the U.S. Olympic Committee, while Kerrigan went to Norway surrounded by questions over her fitness.

The reason? She had been attacked, struck in the knee with a metal baton by Harding’s ex-husband, Jeff Gillooly.

Kerrigan became the skating world’s sweetheart. Harding was its villain. So there was great rejoicing in Olympic circles when Harding finished eighth and Kerrigan won the silver medal in what was, at the time, the sixth-highest-rated television broadcast in American history.

Harding was eventually stripped of her U.S. title when she admitted that she knew of the plot to injure Kerrigan but failed to come forward. She was given a suspended sentence and, in 2003, began hitting people for a living as a professional boxer.

Run, Rosie, run!

Rosie Ruiz was first woman across the finish line in the 1980 Boston Marathon, but she wasn’t the winner. Suspicions arose as soon as Ruiz crossed the tape — she didn’t appear on any of the videotapes of the race, and she wasn’t breathing hard or sweating all that much for someone who had just run more than 26 miles, especially in record time.

The next day, Ruiz was stripped of the victory, which went to “runner-up” Jackie Gareau. She has never admitted cheating, but the accepted version of events is that she ran the first mile or so and hopped the subway for the next 24 miles.

All she would say was that she woke up that morning with a lot of energy.

Just plain foul

Then there is Ty Cobb. No one scandal attaches to his name. Instead, his entire career with the Detroit Tigers, remembered as much for his hatefulness, spite and gamesmanship as for his greatness, qualifies as a scandal. No one has ever topped his career batting average of .367, and no one has ever matched his pure meanness.

By reputation, Cobb sharpened his spikes to a razor’s edge to cut up infielders when he was running the basepaths — a legend Cobb eventually denied but let live as long as he played because his opponents believed it.

He went into the stands and beat up a fan — who was missing one hand and most of another — for heckling him. He was a racist, once trying to choke the wife of a black groundskeeper whose work wasn’t up to his standard.

He was so disliked that his teammates on the minor-league Augusta (Ga.) Tourists — one of whom he pummeled for beating him to the shower — refused to room with him.

He was so disliked as a rookie with the Tigers that his teammates hazed him so brutally that he had a mental breakdown and spent 44 days in a sanatarium.

He was so disliked that the Cleveland Indians turned down the chance to trade for him in 1907, at the height of his greatness.

He was so disliked that on the final day of the 1910 season, the St. Louis Browns allowed his closest rival for the American League batting title, the Indians’ Napoleon Lajoie, to rack up seven base hits in a double-header to beat him. Six of the hits were bunts that the Browns’ third baseman did not field. The seventh was a triple that the Browns’ outfielder said he “lost in the sun.”

He was so disliked that when he was cleared of gambling in 1926 and rescinded his retirement, the Tigers refused to take him back.

Here’s the clincher:

When Tyrus Raymond Cobb died in 1961, only four people from the baseball world — none from the sport’s front office — attended the funeral of the greatest hitter baseball has ever produced.