A group of engineers was honored Tuesday for concocting a plan using plastic bags, cardboard and duct tape to save Apollo 13’s astronauts after their spacecraft was crippled by an explosion 35 years ago.

Astronauts Jim Lovell, Fred Haise and Jack Swigert would have died without the engineers’ quick thinking, said John Schneiter, president of GlobalSpec, the New York company that presented the award — a crystal globe.

Sunday marked the 35th anniversary of the spacecraft’s return to Earth after their aborted moon mission. It was crippled by an oxygen tank that overheated and exploded, raising concerns the carbon dioxide the astronauts expelled from their lungs as they breathed would eventually kill them. Two of Apollo’s three fuel cells, a primary source of power, also were lost.

Engineers advising them from the ground figured out a way to provide them oxygen for the trip home.

“It was clearly a show stopper in this flight,” Haise said Tuesday. “I’m very appreciative and thankful because otherwise, I wouldn’t be here with you today.”

Recognition at last

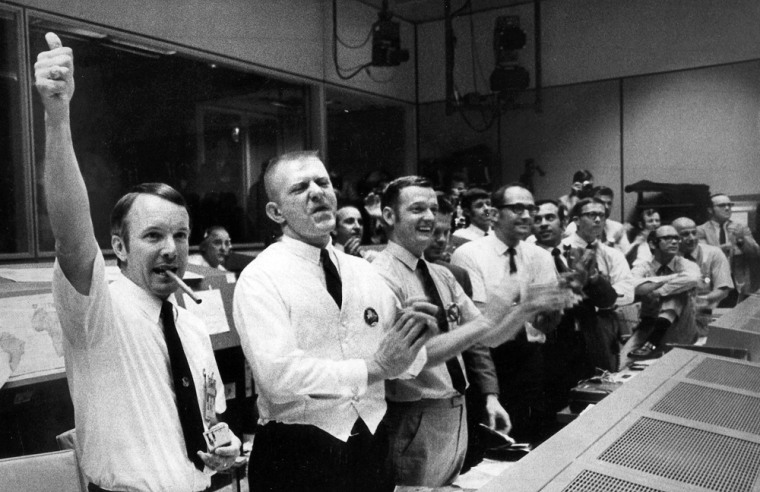

Engineers who solved the problem, astronauts from the Apollo program and others gathered for Tuesday’s ceremony at Space Center Houston, an educational complex next to the Johnson Space Center. The awards presentation took place in a theater that includes the podium from which President John F. Kennedy urged the nation in 1962 to send men to the moon.

About 56 hours into the voyage, Swigert had made the famous call to mission control: “Houston, we’ve had a problem.”

Engineers on the ground had to figure out a solution, and then tell the astronauts how to make the fix. “They had to make it right the first time,” Schneiter said. “It had to work, and son of a gun, it did.”

Ed Smylie, who oversaw NASA’s crew systems division in 1970 and is now an aerospace consultant, was glad the engineering side of the mission was being recognized.

“The guys in the front room are the ones who are in the front lines and get a lot of attention,” he said. “Those of us who are in the back room don’t get a lot of attention.”

At work within minutes

Smylie said he was at home watching television when he learned there was a problem aboard Apollo 13. Within minutes, he was at the space center trying to come up with a solution.

The astronauts had moved to the lunar module from the command module to conserve power for the emergency return to Earth. They had lithium hydroxide canisters to cleanse their spacecraft of carbon dioxide, but some of the backup square canisters were not compatible with the round openings in the lunar module.

“This was equivalent to being on a sinking ship,” Schneiter said. “In this case, you are on a ship that was mortally wounded, and you were simply not going to be able to breathe in a couple of days.”

Smylie and other engineers soon had a proposed solution to retrofit the canisters, but it took a day or two to build a mock-up and get instructions to the crew.

Among the biggest concerns was whether the astronauts had duct tape, Smylie said. He later learned duct tape was commonly used on the spacecraft to clean filters and for other tasks.

“I felt like we were home free,” he said. “One thing a Southern boy will never say is, ’I don’t think duct tape will fix it.”’

While those within the agency may have been concerned, no one showed it, he said.

“If you saw the movie (‘Apollo 13’), it wasn’t like that,” Smylie said, adding there wasn’t any hollering and screaming. “Everything is pretty calm, cool and collected in our business.”

Haise said the device was tricky to build, but it worked.

“Had someone not figured that out, we wouldn’t have survived. ... We had confidence the right people had been brought in and would work it out,” he said.

Looking back, Smylie said, Apollo 13 turned out to be one of the space program’s proudest moments.

“What could have been a horrible disaster turned out to be a great achievement,” he said.