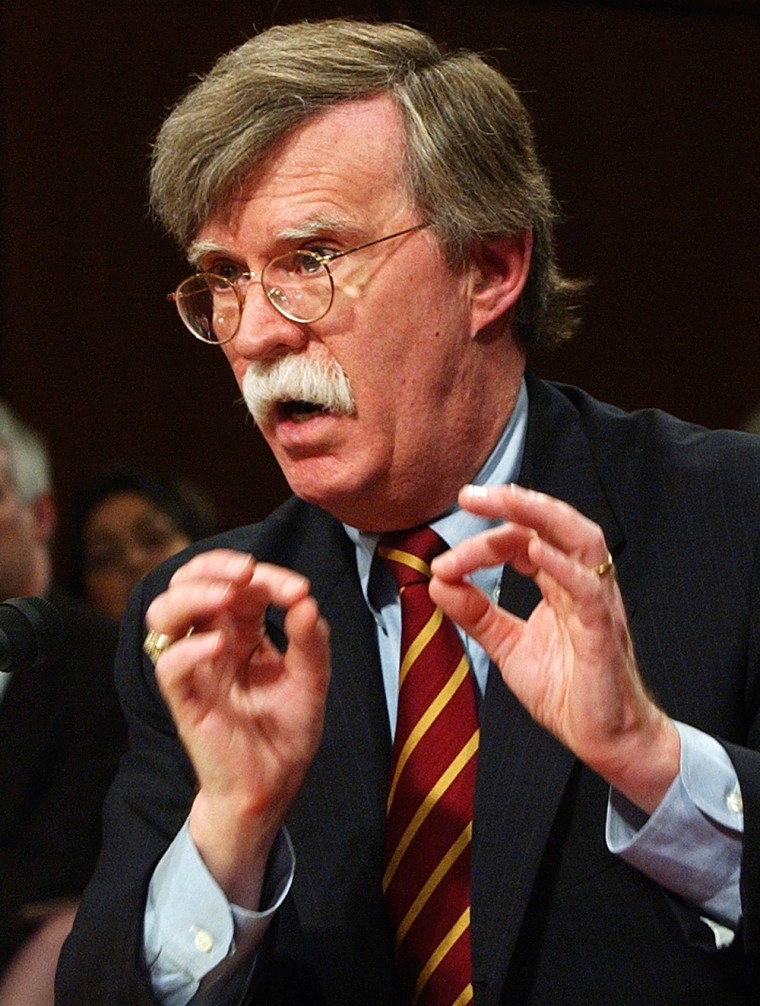

In a major setback for President Bush, the Senate voted Thursday to delay a confirmation vote on John Bolton, Bush’s choice to be U.S. envoy to the United Nations.

Bolton's opponents won on a vote to end debate on his nomination. Under Senate rules, 60 votes were needed to close debate, but the final tally was 56 in favor of ending debate to 42 for continuing debate.

Sens. Mark Pryor of Arkansas, Ben Nelson of Nebraska and Mary Landrieu of Louisiana were the only Democrats to vote for moving to a final vote on Bolton; 53 Republicans voted with them.

Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist was the only Republican to vote against ending the delays, but he only did so because that gave him the procedural right to force the Senate to vote again on the issue.

Sens. Daniel Inouye, D-Hawaii, and Arlen Specter, R-Pa., did not vote.

Specter had left Washington at 4 p.m. — which made it appear at that point that the Republican leadership had more than enough votes to reach the 60 they needed.

Bad miscalculation

It was clear in the aftermath of the dramatic action on the Senate floor that the Republicans had badly miscalculated their vote tally.

Sen. Norm Coleman, R-Minn., accused the Democratic leaders of reneging on a commitment that some Democratic senators would vote for ending debate.

At least one Democrat who had said Wednesday that she would vote for ending debate on Bolton's nomination — Sen. Dianne Feinstein of California — voted "no" on the motion.

Two Democratic senators, Sen. Chris Dodd of Connecticut and Sen. Joe Biden of Delaware, had worked Thursday to round up the votes needed to stop Bolton, and in the end they were successful.

Biden and Dodd were trying to use the cloture vote as leverage to force the Bush administration to hand over documents on Bolton's work on Syria and on weapons of mass destruction.

Bolton now serves as Under Secretary of State for Arms Control and International Security. His portfolio includes preventing the spread of nuclear, biological and chemical weapons.

For Biden, one of the key questions had been, as he told reporters Wednesday, “Did Bolton attempt to badger or change the views of intelligence officers relating to whether or not Syria had weapons of mass destruction at critical juncture (in July 2003) when all of you and all of us were asking ‘Is Syria next?’”

Dispute over Syria documents

Biden accused the Bush administration of withholding the Syria documents because the papers and e-mails would “show that Bolton tried to intimidate the intelligence community” into concurring with “an assertion that it was highly probable that Syria had weapons of mass destruction” in 2003.

Stung by the defeat, Frist issued a statement condemning the Democrats. "Some 72 hours after hailing an agreement that sought to end partisan filibusters, the Democrats have launched yet another partisan filibuster," Frist said.

On Monday night, 14 senators, seven from each party, signed an agreement to not use filibusters to stymie judicial nominations, except in "extraordinary circumstances."

Some senators viewed that accord as a sign of detente, but the good feeling proved to be short-lived.

"It shows what the attitude is of the Democratic leadership: it is to slow-roll, block, and obstruct everything," complained Sen. Trent Lott, R-Miss. right after the vote. "They have pushed it over the edge one time too many."

Democrats fired back that Frist had only himself to blame.

"Remember it was the majority that set the agenda and decided to bring up this nomination," Dodd told reporters. "This vote was not about John Bolton, this was about the Senate as an institution having legitimate access to information that has been sought for almost two months."

One result of the vote: an even more intense animosity between the two parties.

"I had hoped that the vote would turn out differently," said Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz. "Sen. (Harry) Reid (the Senate Democratic leader) had told Sen. Frist that he (Frist) had the votes.... Sen. Reid had a miscount of his votes. But in this atmosphere of trust, you've got to take people's word."

"The Democratic Leader did indicate to the Majority Leader that they intended to help him get votes for cloture," said Frist spokeswoman Amy Call after vote.

But Reid spokeswoman Rebecca Kirszner gave a conflicting account: "Sen. Reid and Sen. Frist talked today. Sen. Reid told Sen. Frist he (Frist) would be unable to get the 60 votes for cloture."

The scene on the Senate floor was one of dramatic political theater.

The vote was set to begin at 6 p.m., but immediately it was clear that something had gone amiss.

On the floor, as 60 other senators watched and waited, a group of seven senators — Frist, Reid, McCain, Dodd, Biden, plus Foreign Relations Committee chairman Richard Lugar and GOP Whip Mitch McConnell, gathered in a tight circle, apparently trying to figure out what the vote count would be.

The group dispersed after about 10 minutes. Frist consulted with Reid one on one for another few minutes, then finally signaled to presiding officer Sen. Lisa Murkowski, R-Alaska, that the vote should begin.

Pleading for Salazar's vote

Sen. Ken Salazar, D-Colo., appeared to be an undecided vote for much of the day.

During the roll call, first Sen. Barbara Boxer, D-Calif., a Bolton foe, and then Coleman, a Bolton ally, talked to Salazar in the front of the Senate chamber, each in turn apparently pleading with him to vote their way. In the end Salazar joined most other Democrats and voted against the motion to shut off debate.

Thursday’s vote lasted about 50 minutes — far longer than the 15 minutes generally allowed for roll calls.

In addition to the Syria documents, Biden and Dodd also want information from the National Security Agency on electronic intercepts — phone conversations and e-mail traffic — involving ten U.S. citizens.

The bad blood between Senate Democrats and Bolton stretches back 20 years.

In 1986, when he served as assistant attorney general in charge of liaison with Congress, he battled Sen. Edward Kennedy, D-Mass. over the nomination of William Rehnquist to be chief justice.

The issue then — as now with the Syria documents — was the executive branch withholding information that senators wanted.

Kennedy wanted memos Rehnquist had written while serving in the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel. Despite a scolding from Kennedy in a public hearing of the Judiciary Committee, Bolton rejected his demands.