Several years ago journalist John Lenger told a remarkable story in the Columbia Journalism Review about teaching a journalism class at Harvard’s extension school. He asked his young students to write a story about a Harvard land deal that occurred in 1732, but after a week of research, most came back with almost nothing substantial to report. The problem: They had done most of their research using the Internet, walking right past Harvard’s library and archives, where the actual information could be found. When Lenger questioned their research methods, one student replied that she assumed that anything that was important in the world was already on the Internet.

When I told that story recently to Brewster Kahle, the founder of the San Francisco non-profit Internet Archive , he shook his head: “When we were growing up,” he said, “we had great libraries. But for kids today, the Internet is their library. We are giving them an instantly accessible resource that is much worse than what we grew up with.” But Kahle, along with Google , Amazon and a clutch of prestigious libraries worldwide are all working to change that: digitizing thousands of books every day, building a global library where every manner of content lives online.

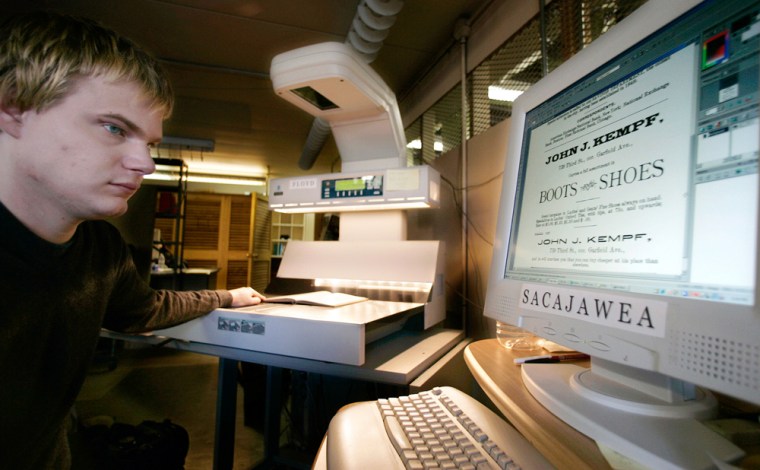

Turning books into bits, however, is not easy: each page must be scanned individually. Until recently, that was a slow and labor-intensive process — often outsourced to countries like the Philippines or India. Now, however, several companies are producing book-scanning robots. One Swiss model, now in use at Stanford, can scan more than 1,000 pages an hour, turning the pages with delicate puffs of air; it costs, however, north of a half million dollars. An American version, from Kirtas Technologies, is less costly at $100,000 to $150,000; the Rochester Public Library in New York recently became its first customer. And at the Internet Archive in San Francisco, Kahle and company are bolting together an even cheaper scanning system — dubbed “Scribes” — that will travel to libraries around the country. Even with all this technology, however, the digitizing will take years and enormous amounts of money. Stanford recently pegged the cost of digitizing its 8 million volume library at a quarter of a billion dollars.

Some might consider turning real books into ephemeral data a step backward in terms of preserving the world’s knowledge, but in fact it’s just the opposite: Physical libraries aren’t necessarily dependable repositories of information. That starts with the great Library of Alexandria, founded around the third century BC. The library was said to include hundreds of thousands of scrolls — even Aristotle’s personal collection — but it was destroyed sometime early in the first millennium of the common era, wiping away forever most of humankind’s first writings. It was no accident that when Egypt opened a new Library of Alexandria in 2003, the institution promptly dedicated itself to digitizing 15,000 Arabic books annually, as well as participating in the Carnegie Mellon Million Books digitization project that will share digital collections worldwide. “Governments burn libraries,” says Kahle, “societies go up and down, Iron Curtains go up and down. Having copies in multiple places is the best way to preserve knowledge.”

The copyright challenge

But making copies can also be a problem. One big hurdle for the universal Internet library is copyright. A physical copy of a book can’t be checked out by more than one person at a time — but unless there are controls in place, dozens of people could read a digital copy at the same time. That’s a problem for publishers and authors who make their living by selling books — and U.S. libraries alone buy enormous quantities of books each year. As a result, a coalition of academic publishers recently protested Google’s current library digitization project, seeking reassurance that Google’s digital copies won’t someday be used to replace demand for the physical copies.

Kahle and the Internet Archive are confronting another copyright issue in the United States. For many years, the government required authors to renew their copyrights in order to keep their books from moving into the public domain. Over the past twenty years, however, Congress has significantly lengthened the period that books remain under copyright — and more importantly, those books now remain in copyright without any further action by the author. As a result, there are hundreds of thousands of “orphan books,” still in copyright but whose authors may have died or lost interest in their creations. In earlier years, those books would have moved into the public domain, but now they technically remain under copyright — meaning that libraries and universities are very cautious about making digital copies as they may find themselves sued for infringement. Kahle is currently pursuing a court challenge to clarify the question of digitizing such orphan books. “Much of the 20th century’s media is locked up,” he says. “Very little is being exploited because of the copyright explosion.”

When Kahle’s vision comes true and books are accessible from any browser, exactly where will the neighborhood library fit in? That’s a key topic at this week’s 124th annual American Library Association conference in Chicago. At the moment, libraries are doing a thriving business: Between 1992 and 2002, library visits more than doubled, and the number of items checked out increased about 30 percent. Librarians, however, acknowledge that the increase in visits was in part due to the availability of Internet access — begging the question of what happens when, someday, everyone has Internet access at home.

Changing role of librarians

Most librarians foresee a different, but still essential, role. “Library spaces are changing,” says Carol Brey-Casiano, the current president of the ALA. “Card catalogs are going away, computers are coming in. But libraries still offer trained research professionals — there’s a real danger in going straight to Google.” Brey-Casiano adds that nearly 50 percent of the questions her own public library in El Paso receives “are about Internet research: how to narrow their search, whether a resource is reliable.”

Libraries, in short, are already evolving into community digital research centers, staffed with professional guides to the vast quantities of text, audio, video and images available online, and equipped with the latest digital playback devices, from video screens to printers to audio systems. In the long run they will, almost inevitably, house fewer physical books; Helsinki, for example, has a new, nearly bookless branch focused on technology and multimedia. And when students return this fall to the University of Texas in Austin, they will find that nearly all of the undergraduate library’s 90,000 volumes have been sent elsewhere to make room for a 24-hour “information commons.”

Many libraries now provide free access to online databases that would otherwise charge subscription fees. And increasingly, they are also offering new books — printed or audio — in digital format. The New York Public library, for example, offers both audio and e-books on a Website; users check out their choices by downloading and then each e-book remains “live” for twenty-one days. Many libraries also provide a gigantic digital card catalog that lets you search the holdings of thousands of libraries worldwide. The largest such card catalog, WorldCat, maintained by the library cooperative OCLC, lists close to a billion holdings—and is also integrated into Yahoo, so your searches there show not only relevant books but also where the nearest library copy is located.

Indeed, keeping track of what’s out there may be the largest challenge of all. “We are going to be able to create a great deal of knowledge,” says Cathy De Rosa, vice president of library services for OCLC. “There are millions of items that exist only one place in the world—the ability to mobilize those resources is extraordinary, so your research can include the book, the map, the sound recording, the journal article, even the original manuscript. The problem is: how do we put it together?” As the technologists digitize, librarians will organize—and somewhere out in the future will finally arrive what Kahle calls “the library we owe our children.”