Two spacewalking astronauts armed with caulking guns, putty knives and foam brushes practiced fixing deliberately damaged shuttle heat shields Saturday, as NASA extended what could be its last trip to the space station for a long while.

With future shuttle flights grounded because of Discovery's fuel-tank foam loss during liftoff, mission managers decided to keep the crew at the international space station an extra day to haul over surplus supplies and help with station maintenance.

It could well be next year before the foam problem is fixed and a shuttle returns to the space station.

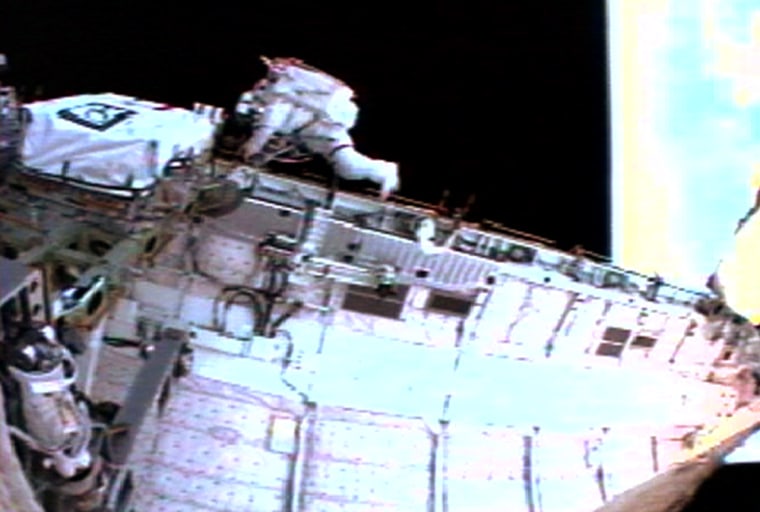

The two spacewalkers, meanwhile, practiced repair maneuvers they hope they'll never have to do for real.

The tests were designed in the wake of the 2003 Columbia tragedy and aren't related to the damage Discovery suffered during lift off. NASA officials say Discovery received some scrapes and chips but nothing that appears to warrant orbital repairs.

Astronauts Soichi Noguchi and Stephen Robinson worked on samples of thermal tile and panels that were cracked and gouged before flight. They squeezed dark goo into the crevices as the sticky material got on their gloves and clumped at the ends of their putty knives. Spacewalk managers had feared a much bigger mess, though, and were pleased with the relative neatness of it all.

"It's about like pizza dough, like licorice-flavored pizza dough," Robinson said as the near-black filler material oozed from his high-tech caulking gun. He used a putty knife to smooth down the substance, again and again.

"The cleaner it is, the better work you do, just like anything," he added, holding out his knife for Noguchi to wipe.

The astronauts reported some bubbling in the two repair materials _ a paintlike substance for the thermal tiles that cover most of a shuttle, and a thick paste for the reinforced carbon panels that line the wings and nose cap. The paste swelled up in the cracks like rising dough and, as the experiment wore on, was harder to get to stick because of colder-than-desired temperatures outside.

It was all valuable feedback; engineers wanted to see how their creations fared in the weightlessness of space for possible future use in an emergency. Neither the bubbling nor swelling was surprising, said Cindy Begley, the lead spacewalk officer.

Columbia's astronauts had no such tools or techniques at their disposal. Of course, neither they nor flight controllers knew Columbia had a gaping hole in the left wing, left there by a 1.67-pound chunk of fuel-tank foam insulation that broke loose at launch.

A piece of foam just over half that size came off Discovery's external fuel tank during last week's liftoff. It missed Discovery, but was enough to ground all future shuttle flights. A smaller foam fragment may have struck the right wing, but lasers and other sensors found no evidence of damage.

None of the repair kits flying on Discovery could mend a hole the size of the one responsible for Columbia's catastrophic re-entry, estimated between 6 and 10 inches across. It could be years before engineers come up with such a big patch. For now, the largest hole that any of the repair methods aboard Discovery could tackle would be 4 inches.

The astronauts will test a third repair technique, essentially a plug, inside Discovery later this week.

Once the repaired samples are back on Earth, engineers will analyze them to see how deep and how well the filler material penetrated. None will be torched, however, to simulate the searing heat of re-entry. The spacewalkers had to skip the one sample intended for laboratory test-firing because they ran out of time.

In the first of three spacewalks planned for what now is a 13-day mission, Noguchi and Robinson also made some long-overdue space station repairs. They restored power to a gyroscope that stopped working four months ago and replaced a broken Global Positioning System antenna.

"Great job. Everything was just perfect. Extra stuff got done," Mission Control radioed as the seven-hour spacewalk came to a close. "You guys get some rest."

As soon as Robinson and Noguchi were back inside, their shuttle crewmates pulled out their 100-foot, laser-tipped inspection crane to survey Discovery's left wing one more time. Engineers wanted to make sure they didn't miss any signs of damage.

On Monday, NASA expects to wrap up all its analysis of Discovery's thermal shielding and give the final safety clearance for the shuttle's descent on Aug. 8, a day later now than originally planned. A final decision was expected Sunday, but was put off to give engineers a little more time to analyze a couple of protruding gap fillers between thermal tiles.