Space shuttles have always been thrilling to watch blast off, with the bone-shaking roar in your ears and the threat of fiery disaster always in mind. But with Discovery, the real tension comes at the end of the mission, as people watch its fiery descent through the upper atmosphere. As this week’s in-space inspections and repairs have underscored, that is where the greatest danger now lies.

On Feb. 1, 2003, the very first people to see evidence that the returning Columbia shuttle was in trouble were amateur astronomers in California. Watching through a video camera as sparks fell away from the main fireball, one young man could be heard to say, “Dad, there are pieces coming off.”

And indeed there were. A mortally wounded shuttle wing was already shedding fragments of its disintegrating heat shield. The eyewitness accounts, as well as numerous photo and video records, provided important forensic data for the investigators who ultimately found the cause of the disaster.

There were some notable detours, such as speculations about a bizarre image captured by Bill Goldie, an image processing specialist from the San Francisco area. The first of a series of time exposures that he took that morning seemed to show a zig-zag purple bolt of lightning converging on the passing shuttle. At first, some researchers wondered whether it was some unknown ionospheric phenomenon, or even an artifact of some experiment.

A much more prosaic answer soon was found, however: Goldie had manually depressed the camera’s button while Columbia was in the center of the field of view, its milky white trail already marked across the sky. The camera briefly jiggled until it settled. The zig-zag trail was from the fireball itself, and once stable, the camera recorded the persistent trail that already existed, as well as a brighter segment where the fireball proceeded out of the field of view.

Since the early days of the shuttle program, amateur astronomers have captured spectacular and thrilling views of a shuttle entry, under far happier circumstances. Unfortunately for American observers, such a view will never be visible again from the United States. Well, perhaps once more….

Rare occurrence

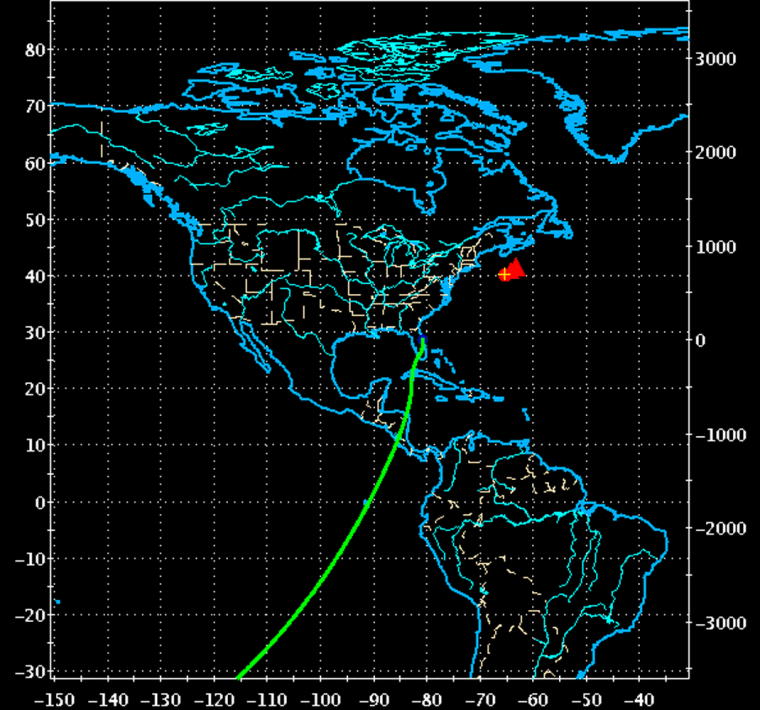

Out of the 112 space shuttle re-entries, only about a dozen crossed the United States from west to east, from California across Arizona and New Mexico and Texas, in darkness. Most missions landed in daylight, or at Edwards Air Force Base in California, their fiery trails visible only over the Pacific. Many others flew on orbits more steeply inclined to the equator, so their approach to Florida wasn’t directly from the west, but from the southwest. A few came in from the northwest, across the Ohio Valley, but lighting and weather conditions in those cases were poor.

All (except perhaps one) of the future shuttle missions will fly to the space station, with its northerly orbital path. Therefore, all future entry fireball trajectories will come across the Central American region, crossing the coast somewhere between Panama and Mexico's Yucatan Peninsula. The path may lie a few hundred miles west on one mission, a few hundred miles east on another. These paths will never again trace a fireball through the skies over the United States.

Shuttles have been landing along this path for about a decade, returning from visits to the Russia's Mir space station and from the international space station. But as far as press reports can tell us, nobody in the area who may have seen the fireballs recognized them for what they really were. Perhaps they were just filed away as another "OVNI" tale — an “objeto volante no identificado,” the Spanish-language equivalent of a UFO.

For the return of Discovery, now set for Monday, NASA will pay tribute to the work of the Columbia-watching amateur astronomers whose enthusiasm and skills put them at a crucial observing point, by capturing views of the re-entry with high-flying camera-carrying aircraft. But if the observations turn up nothing unusual, this expensive airborne effort will be terminated by early 2006, leaving the fireball skies once again solely to the eyes of amateurs.

‘Claros cielos’ in Central America

And so another population of amateur astronomers, this time in Central America, will become familiar with the awesome sight of a golden-yellow spark in stately procession, followed by a slowly fading white trail, followed many minutes later by the dull thud of a sonic boom. NASA plans about 20 more missions to complete the space station, and probably a fifth of them will be landing at night. Millions of people will be able to see them, assuming "claros cielos" — the astronomers’ wish for "clear skies."

The last chance for U.S. observers would come about if a shuttle mission to repair the Hubble Space Telescope is approved, and if the mission schedule requires a launch date that can only be achieved with a night landing. If the skies over Arizona, New Mexico, Texas and Louisiana are clear on that one night, one last golden yellow shining spark will leave its milky white trail across U.S. skies.

But when Discovery returns from space just before dawn on Monday, and if the alert is widely publicized in the local news media and over the Internet, people along the descent path will see with their own eyes that sparks are not coming off the fireball, that the path is stable and true, and that the astronauts are headed for a safe landing. And minutes after the spark has set behind the northeastern horizon, a distant thunderclap will punctuate the passage of a reborn spaceship.