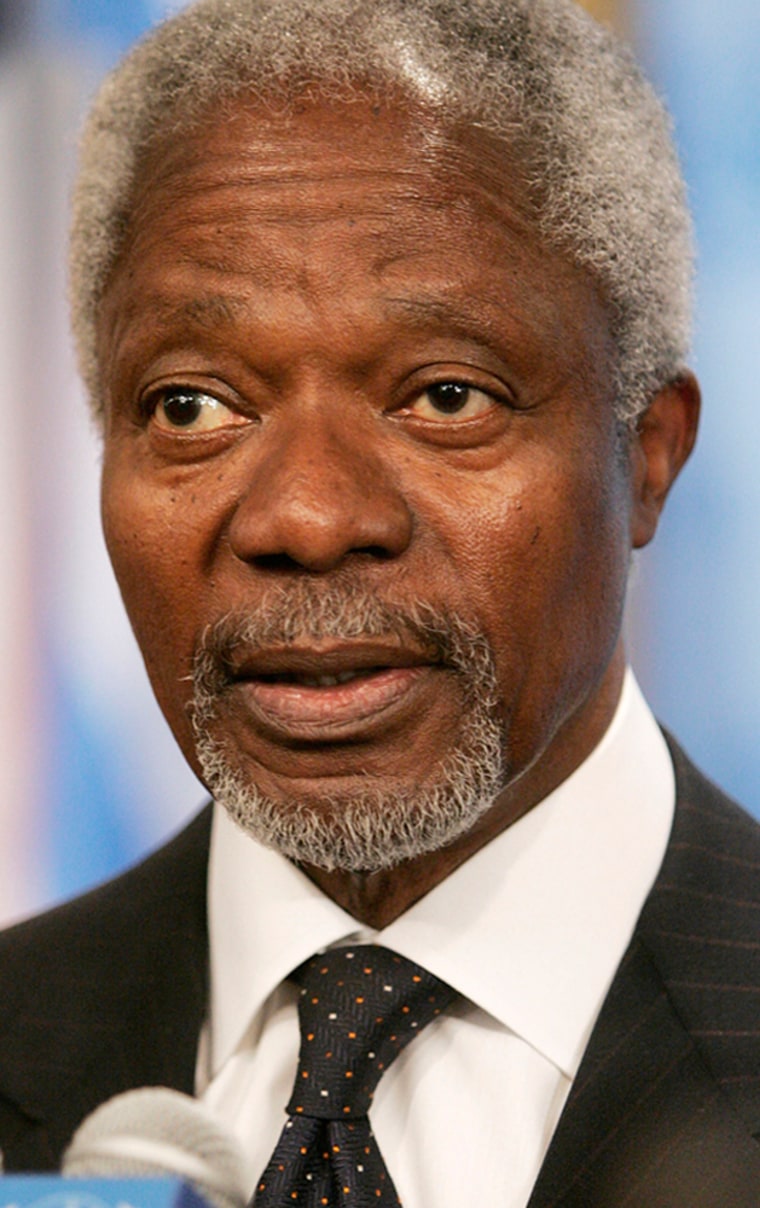

In a devastating assessment of the U.N. oil-for-food program in Iraq, investigators strongly criticized Secretary-General Kofi Annan, his deputy and the Security Council for allowing Saddam Hussein to bilk $10.2 billion as a result of the giant humanitarian operation.

Annan said he took personal responsibility for the lapses, but he stressed he had no plans to resign. "The report is critical of me personally, and I accept the criticism," he said.

The Independent Inquiry Committee's definitive report on the oil-for-food program said those managing the program — both U.N. member states and the world body's staff — failed the ideals of the United Nations, ignoring clear evidence of corruption and waste that flourished after it was created in 1996.

"The inescapable conclusion from the committee's work is that the United Nations organization needs thorough reform — and it needs it urgently," the report said.

Report comes a week before summit

The report's conclusions and its strong urging for change come a week before world leaders gather for a summit in New York to consider a host of Annan's own reform initiatives. Many of his proposals have stalled — including ones similar to the committee's — because of deep divisions among member states. The United States and other supporters of U.N. reform hope the report will provide much-needed impetus.

"This report unambiguously rejects the notion that business as usual at the United Nations is acceptable," U.S. Ambassador John Bolton said. "We need to reform the U.N. in a manner that will prevent another oil-for-food scandal. The credibility of the United Nations depends on it."

Former U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker, who was the chairman of the investigation, came to the Security Council to present the report at a meeting attended by Annan.

"In essence, the responsibility for the failures must be broadly shared, starting, we believe, with member states and the Security Council itself," Volcker told the council.

The committee said the instances of corruption that reached the top of the program reflect the absence of a strong institutional ethic in an organization that should exemplify the highest global standards because of its "unique and crucial role."

Acknowledgment of some success

Yet it also acknowledged that the program was partly successful, providing minimal standards of nutrition and health care for millions of Iraqis trying to cope with tough U.N. sanctions imposed after Saddam’s 1990 invasion of Kuwait. It also helped keep Saddam from obtaining weapons of mass destruction, the report said.

And it said that the United Nations is essentially the only organization of its kind in the world that is capable of taking on such daunting tasks.

One of the largest humanitarian programs in history, oil for food was a lifeline for 90 percent of the country's population of 26 million. But Saddam was allowed to choose the buyers of Iraqi oil and the sellers of humanitarian goods, and used that power to curry favor by awarding oil contracts to former government officials, activists, journalists and U.N. officials who opposed the sanctions.

Iraqi people slighted, ambassador says

Iraq's U.N. Ambassador Samir Sumaidaie said the Iraqi people did not get "full value for their money," which funded the oil-for-food program.

"For various reasons they were robbed of a great deal of what was theirs by right. The lessons will continue to be studied, and various actions will be taken, but that loss is permanent," he said.

The 1,036-page report in five volumes was highly critical of the almost total lack of oversight of the program by the secretary-general and Deputy Secretary-General Louise Frechette, who was the direct boss of Benon Sevan, the program's executive director, who is now being investigated for allegedly accepting kickbacks.

Program let funds slip to Saddam

It said lax oversight of the program allowed Saddam's regime to pocket $1.8 billion in kickbacks in the awarding of the contracts.

Annan accepted the criticism in a briefing to the council.

"The findings in today's report must be deeply embarrassing to us all," Annan said. "The Inquiry Committee has ripped away the curtain and shone a harsh light into the most unsightly corners of the organization. None of us — member states, Secretariat, agencies, funds and programs — can be proud of what it has found."

No resignations expected

Despite the criticism of him and his deputy, Annan told reporters afterward: "I don't anticipate anyone to resign. We are carrying on with our work."

The committee also accused top U.N. officials and the powerful U.N. Security Council of turning a blind eye to the smuggling of Iraqi oil outside the oil-for-food program in violation of U.N. sanctions. That poured much more money — $8.4 billion — into Saddam's coffers from 1997-2003.

Saddam pocketed an additional $2.6 billion before the program started from illegal oil sales in violation of sanctions, the report said.

Volcker's team repeated previously known charges that the five permanent members of the U.N. Security Council — Britain, China, France, Russia and the United States — repeatedly looked the other way or sometimes actively supported the smuggling as a way to compensate Iraq's neighbors, who suffered too from the tough trade sanctions against Baghdad.

The report is not shy about assigning blame among those five. It says that France and Britain were cooperative. Russia and China, on the other hand, refused requests for information or access to state-owned companies implicated in the probe. While some branches of the U.S. government were helpful, notably the U.S. mission to the United Nations and the State Department, others were not.

Annan family conflict of interest?

As for the most damaging allegations against Annan, the committee reaffirmed its previous findings that there wasn't sufficient evidence to show that he knew about an oil-for-food contract that was awarded to the Swiss company Cotecna, which employed his son Kojo. Neither was there any evidence to show he interfered in the contract.

Yet, as it had said previously, Annan did not sufficiently investigate conflicts of interest involving his son.

As for Kojo himself, the committee said he used his father's "name and position" in 1998 to buy and deliver a car at a reduced price. It said he had asked beforehand whether he could buy the car in his father's name, but there was no evidence to show the secretary-general ever agreed.

It also described a plot in which the Iraqi government, which wanted U.N. sanctions lifted, tried to influence Annan's predecessor, Boutros Boutros-Ghali, and later Annan's coordinator for U.N. reform, Canadian businessman Maurice Strong.

Baghdad paid millions of dollars to South Korean businessman Tongsun Park and Iraqi-born American businessman Samir Vincent, with the apparent expectation that they would pass money to Boutros-Ghali and Strong. Vincent has pleaded guilty to skimming money from the program.

But the report found no evidence that Boutros-Ghali ever took money from Iraq, or that Strong was even involved in oil-for-food or did anything at their request.

The committee criticized Boutros-Ghali, however, for allowing the oil-for-food program to be established in a way that enabled Saddam to exploit it.