The planet Venus was formed at about the same time as Earth, from the same basic materials. But our "sister" planet turned out to be a very different place from Earth, with lessons to teach about the greenhouse effect and planetary climate.

Next week, the European Space Agency is due to send a probe toward Venus, to learn yet more lessons that could be applied to our scientific understanding of our own planet and other worlds.

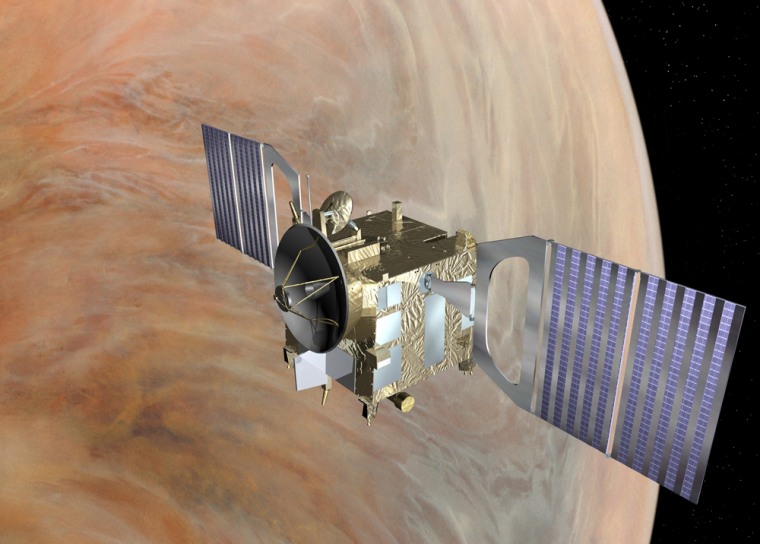

The $240 million Venus Express mission is aimed at exploring Venus' boiling-hot surface and acidic atmosphere, focusing on a central question: Why did Venus evolve the way it did?

“There were great expectations for a benign climate on Venus, and of course we now know it’s not like that," Oxford physicist Fred Taylor explained Monday at a pre-launch briefing in London. "The pressures are crushing, and the temperatures are hot enough to melt lead. So it’s quite inhospitable. We don’t know how long it’s been like that, or if it will stay like that."

Taylor said it's even possible that Venus' climate will become more like Earth's. "There are theories that suggest that. But we need a much better understanding before we can know about things,” he said.

Why so hot?

One of the mysteries the mission is trying to solve is why Venus is so hot. Advanced instruments onboard will peer beneath the thick cloudy atmosphere to find out if volcanoes are to blame. Venus Express will also explore the giant hurricanes that sweep the planet’s surface.

A British-build magnetometer will look at the interaction between the planet’s weak magnetic field and the solar wind, a torrent of electrically charged particles that stream from the sun.

Imperial College space scientist Chris Carr said Earth's magnetic field deflects solar-wind particles so that they don't "cause us any trouble to speak of."

"If you’re at Venus, you have no protecting magnetic field, and this million-mile-an-hour stream of ionization radiation slams straight into the upper atmosphere of the planet,” Carr told reporters.

Understanding this interaction could be of more than just academic interest. Some scientists warn that future climate change could make Earth more like Venus.

“We’re struggling to understand the Earth’s climate, and in particular how it will change," Taylor said. "And it is in fact changing in the direction towards being more like Venus, more CO2 (carbon dioxide) in the atmosphere, higher temperatures. I’m not saying the Earth will ever become as extreme as Venus, but it’s moving in that direction."

The results of the Venus Express mission could "help us to plan our own future and understand it," Taylor said, and perhaps even suggest new ways to avoid the worst-case scenarios for climate change.

A recycled design

Venus has been explored by U.S. spacecraft such as the Pioneer and Magellan orbiters as well as the Soviet Venera probes, but Venus Express represents ESA's first mission to the planet. The 2,800-pound (1,270-kilogram) orbiter was put together at comparatively low cost, and in a relatively short three-year time frame, by adapting the design of the Mars Express orbiter and using spares and copies of instruments from Mars Express and ESA's Rosetta comet probe.

Among the instruments are a camera and three spectrometers, a plasma analyzer, the magnetometer and a radio science experiment.

Liftoff is scheduled for no earlier than Oct. 26 from Russia's Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan, on a Soyuz launch vehicle with a Fregat booster. The launch window extends until Nov. 25.

After a five-month cruise, the spacecraft will settle into an orbit ranging between 156 and 41,000 miles (250 and 66,000 kilometers) above Venus, for what is slated to be a roughly 500-Earth-day primary mission. That translates into just two Venusian days.

"The science data set to return next year will have a huge impact on the way in which we deal with conditions on Earth, demonstrating how the exploration of the solar system has real impact on our daily lives," said Keith Mason, chief executive officer of Britain's Particle Physics and Astronomy Research Council.

This report includes information from The Associated Press and MSNBC.com.