Lily Ding was never much the political type, but that changed in February, she said, when she attended a rally in San Francisco to protest a jury’s second-degree manslaughter conviction of former New York Police Department officer Peter Liang, who fatally shot an unarmed black man by accident in 2014.

Some in the Chinese-American community believed Liang, also Chinese, was offered up as a sacrifice for white officers never indicted in police-related deaths.

“For me, it was a wake-up call,” Ding, who emigrated from China 20 years ago to study, told NBC News. “I have always thought the U.S. had been very fair.”

Two months later, Ding said she learned of another political fight — a movement to defeat a California bill requiring certain state education and health agencies to break down demographic data they collect by ethnicity or ancestry for Native Hawaiian, Asian, and Pacific Islander groups.

She said she heard about it on WeChat, a Chinese-language social media tool that had been used to galvanize nationwide support for Liang, and knew she had to get involved.

“To further disaggregate an already finely disaggregated population just doesn’t make any sense at all,” said Ding, who works as a data scientist.

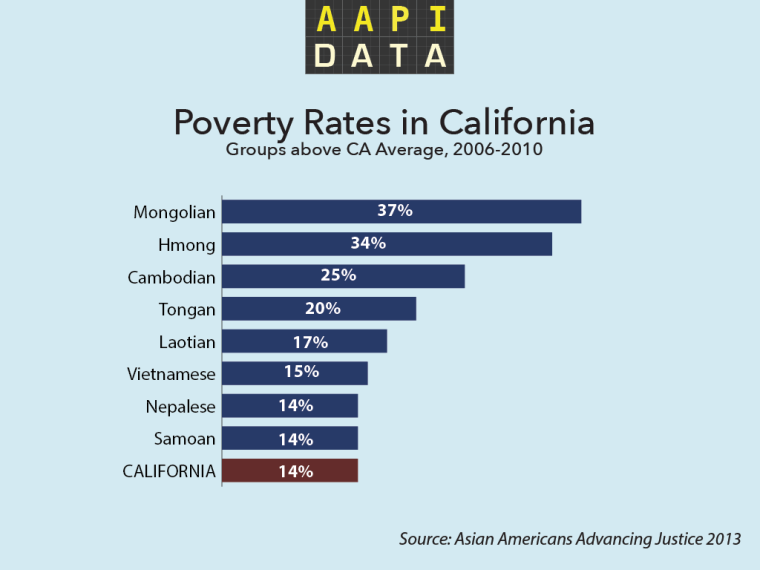

The bill, known as AB-1726, has become a flashpoint in California’s Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) community. Those who support it, including dozens of community and civil rights groups, say separating demographic data by ethnicity — and including at least 10 additional AAPI ethnic groups — can help better expose disparities in healthcare and education. This is particularly true among Southeast Asians and Pacific Islanders, two groups that often get left out, they say.

But critics counter that the bill, introduced in the State Assembly in January, is unfair because it targets only Asians and no other race. They fear it could be a backdoor way of ending California’s ban on affirmative action and say it further divides up AAPIs into unnecessary hyphenated groups.

RELATED: California Advocates Push 'AHEAD' with Data Disaggregation Bill

Some of the bill’s most vociferous opposition come from parts of California’s Chinese-American community. Some activists and organizers, many of them immigrants from China, see the bill as the latest in a series of threats against Chinese Americans trying to achieve social and economic equality — a claim supporters of AB-1726 say is groundless and misplaced.

Both sides have spearheaded online petitions. As of Friday morning, one in support of the bill, created by 18 Million Rising, collected roughly 1,700 signatures. The other against it, on change.org, had approximately 14,000.

An amended version of the bill, authored by Democratic Assemblyman Rob Bonta, passed California’s Senate by a unanimous vote of 39-0 on Tuesday and will head to Gov. Jerry Brown, a Democrat, for signing. One major difference in the bill’s revised language is that AB-1726 now applies to data collected only by the state Department of Public Health — not agencies overseeing public universities or colleges.

The new ethnic or national origin groups included in the bill are Bangladeshi, Hmong, Indonesian, Malaysian, Pakistani, Sri Lankan, Taiwanese, Thai, Fijian, and Tongan. The move would bring California’s collection system in line with that of the U.S. Census.

RELATED: California Governor Vetoes Bill Aimed at Addressing Disparities in AAPI Communities

Brown, however, vetoed a similar bill Bonta introduced last year.

“Dividing people into ethnic or other subcategories may yield more information, but not necessarily greater wisdom about what actions should follow,” the governor wrote at the time.

Bonta told NBC News he’s excited his new bill passed the Senate, even though it won’t apply to the state’s public universities and colleges — many of which voluntarily collect and tabulate such data already.

“With this bill, we are in a better place today than we were yesterday,” he said. “Our goal is to make progress, and we think tremendous progress can be made and knowledge learned that’s incredibly valuable through disaggregated data.”

The federal government has been grouping people in the U.S. since the very first Census was conducted in 1790. Over time, the categories have changed, and different groups have been added — Chinese in 1860, Japanese in 1870, Filipinos, Koreans, and Hindus in 1920, according to Pew.

Since the 1990s, according to Bonta’s office, California law has required state agencies, boards, and commissions to collect data for at least 11 AAPI categories. Those groups include Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, Korean, Vietnamese, Asian Indian, Laotian, Cambodian, Hawaiian, Guamanian, and Samoan.

It also requires that California’s Department of Industrial Relations and Department of Fair Employment and Housing gather and tabulate data for the 10 additional AAPI categories in AB-1726. Roughly 15 percent of California’s population is Asian and 0.5 percent Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, according to the Census.

Originally, Bonta’s bill had asked the University of California system, and required California Community Colleges and the California State University system, to collect data on Native Hawaiians and Asian Pacific Islanders, including the 10 new ethnic groups, and also issue reports on student admissions, enrollment, completion, and graduation rates.

This mandate, which would have standardized collection among state school systems, could have proven particularly useful for Southeast Asian students who tend to have lower academic achievement rates, a data point often lost in the stereotype that all Asian students do well in school, bill supporters say.

“You’re better able to assess risks among your student populations,” Karthick Ramakrishnan, a public policy professor at the University of California, Riverside, told NBC News. “That is why these educational institutions do this, so they can better understand their student populations and they can better serve their student populations.”

But following protests from some in California’s Chinese-American community, the higher education data collection requirement was removed from Bonta’s bill. One of those who helped galvanize opposition against AB-1726 was Mei Mei Huff, wife of Republican state Sen. Bob Huff.

Bob Huff called for a rally Aug. 10 at the state Capitol, which Ding, the Liang supporter, helped organize. In a press release, he likened the data collection in AB-1726 to what Congress used to write and pass the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which restricted immigration from China, and what the U.S. Secret Service employed to put Japanese Americans in internment camps after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

On Tuesday, Bob Huff was one of the 39 senators who voted unanimously in favor of the amended bill.

“On the one hand, I’m happy to see the author took out all the provisions related to education, because I think that was the biggest concern of our community,” Mei Mei Huff, who was born in Taiwan and studied in the U.S., told NBC News. “On the other hand, it does not address the question why the bill only focuses on Asians and not other ethnic groups. We remain very concerned.”

In arguing against AB-1726, opponents often ask why there isn’t legislation that requires demographic data be broken down for, say, whites or Latinos. Ramakrishnan, the UC Riverside professor, noted that the Census already collects “detailed origin data” for the Hispanic or Latino population, allowing respondents to choose such identifiers as Mexican or Dominican, among others.

But he added that unlike Asian Pacific Islanders and Native Hawaiians, who represent more than 50 ethnic backgrounds and speak over 100 different languages, Hispanics and Latinos simply haven’t been asking for disaggregation.

“It’s just that in the education and health context, there has not been a major push because people have not found huge differences by national origin on many of these outcomes,” Ramakrishnan said.

“We wanted to pass something in an area where we can add tremendous value, where the community was asking for it, where the diversity in the AAPI community really increases the value that it can provide.”

Much of the wariness among Chinese Americans about data collection circles back to another controversial issue: higher education and affirmative action, they said. Some organizers and activists involved in the AB-1726 fight also took up the battle two years ago to stop passage of California’s Senate Constitutional Amendment 5 (SCA-5), which would have ended the state’s ban on affirmative action in college admissions.

Proposition 209, passed by public vote 20 years ago, forbids the use of race, sex, color, ethnicity, or national origin for public college or university admissions decisions in California. Many Chinese-American parents fear that should the ban be lifted, Chinese-American enrollment rates at prestigious University of California schools will plummet, nixing opportunities for their kids to earn admission to good state schools based on merit, according to Huff.

“That was a wake up call to the Asian, especially the Chinese community,” Huff, who chairs the San Gabriel Valley chapter of the Lincoln Club, a Republican political action committee, said. “That’s why you see all this opposition now, simply because what happened in 2014. They are very concerned that bills such as AB-1726 will just be like a back door seeking to overturn Proposition 209.”

Ding agreed, adding that Asian-American groups have also filed complaints with the federal Education Department, accusing Ivy League schools of discriminating against Asian Americans in the admissions process.

“SCA-5 was shut down by the Asian-American community as a whole, because everybody could see the intention of that,” said Ding, a committee member of the Silicon Valley Chinese Association. “So they figured they’re not going to be able to pass that, so they reenacted AB-1726.”

Bonta, the bill’s author, said AB-1726 has nothing to do with affirmative action whatsoever.

“This bill makes no policy decisions besides the fact that we should collect disaggregated data and that if we have more information, it can help guide our policy decisions,” he said.

Ramakrishnan said he believes these fears stem from a misunderstanding of data disaggregation.

“If you connect data disaggregation to affirmative action and also to the Chinese Exclusion Act and Japanese internment — essentially if you’re able to increase anxiety and fear among people, that they’ll not only be shut out of universities but also may be kicked out of the United States because people are finding out who the Chinese are — that will get people mobilized, that will get people to the streets,” he said.

“We’re just able to have much better public policy if we’re able to compare apples to apples, as opposed to different agencies in California collecting this data in vastly different ways."

If AB-1726 is signed into law, it would require the state Department of Public Health, beginning July 2022 and depending on funding, to collect demographic data broken down by ethnicity or ancestry for Native Hawaiians and Asian and Pacific Islanders. The reports would include rates for major diseases, leading causes of death, subcategories for leading causes of death, pregnancy rates, and housing numbers.

Ramakrishnan said there are significant differences among Asians when it comes to risks for Hepatitis B, cancer, and cardiovascular disease. Requiring this data to be categorized by ethnicity helps the Department of Public Health better understand the health risks of each group and structure their programs accordingly, he said.

“We’re just able to have much better public policy if we’re able to compare apples to apples, as opposed to different agencies in California collecting this data in vastly different ways, so that we’re not able to match up to what’s going on on the federal level,” Ramakrishnan added.

But Ding raised concerns about the culling and reporting of such numbers. She said allowing respondents to choose their own ethnicity could lead to inaccurate and unscientific results. She said she also believes health statistics in California should be reported for all racial and ethnic groups, not just Asians.

For Bonta, who said criticism of his bill to a “very small but very vocal group from the Chinese community,” separating data into ethnic groups is something that can help not just AAPIs but also Latinos, blacks, and whites.

He added that other races weren’t included in this bill because of budgetary and appropriation constraints.

“The bigger we make the bill, the more expensive it is, the less likely it is to pass,” he said. “We wanted to pass something in an area where we can add tremendous value, where the community was asking for it, where the diversity in the AAPI community really increases the value that it can provide.”

RELATED: New Data Disaggregation Initiative Announced by Dept. of Education

Bonta said disaggregation for other communities should be taken up in the future if there’s interest. For its part, the federal Education Department invested $1 million in May to offer grants to encourage state education agencies to evaluate disaggregated data for English learners and AAPI groups, beyond the existing seven racial and ethnic categories. California did not apply for the grant since its school districts already collect that data.

For Ding and Mei Mei Huff, though, any disaggregation is already too much, they say.

“It’s reminding Asian Americans that you are not truly American,” Ding said.

Follow NBC Asian America on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Tumblr.