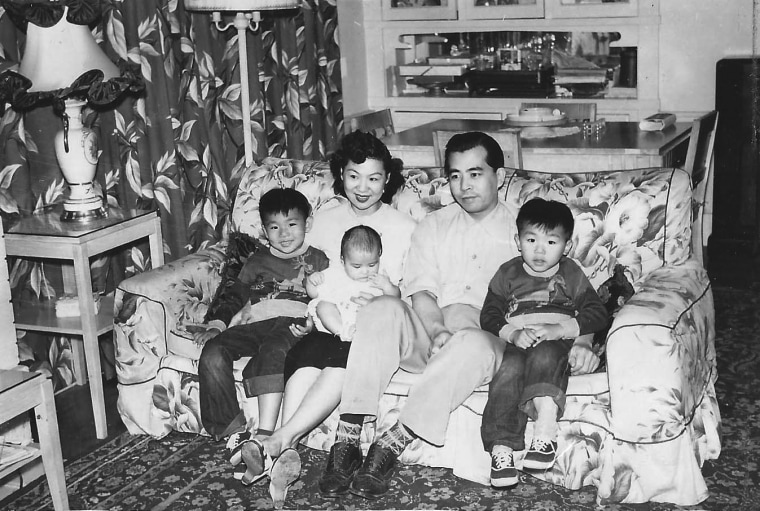

Born in 1948 in Chinese Hospital, in the heart of San Francisco’s Chinatown, Gordon Chin never strayed far from the neighborhood.

In his fascinating new book, "Building Community, Chinatown Style," Chin writes about his decades as an activist, the Asian American movement, and how the organization he founded – the Chinatown Community Development Center – works on issues like transportation and public space to preserve the area he came to call home.

During the 1968 student strike at San Francisco State University – which helped establish ethnic studies classes there and at colleges across the country – Chin’s parents considered it an embarrassment that their son challenged authorities and dared to appear on television and newspapers.

Years later, they were proud when he was photographed beside the mayor of San Francisco, even though his progressive politics had remained the same.

“They understood I was an emerging leader for their community, and I was a proud symbol of many generations of our family in that place we call Chinatown. Place matters and family matters. And of course, cutting my hair and wearing a suit helped, too,” Chin writes. He retired in 2011 but remains active on boards.

Randy Shaw, director of the Tenderloin Housing Clinic, described the book as the “true history of how Chinatown survived as a low-neighborhood,” on his website BeyondChron. “Instead of promoting himself, Chin believed in empowering his staff, which is why CCDC has attracted and retained so many talented activists” and “created a model for community building that other neighborhoods can follow.”

NBC Asian America recently caught up with Chin to talk about his story and Chinatown’s.

Do you have any insight on emerging American activists and political leaders and how they deal with such familial concerns, or if it’s become any easier thanks to your generation of activists?

Asian American youth and young adults face the same generation gap challenges as other young people in America. For young Asian American activists, the challenge may be exacerbated if their parents are culturally more traditional or politically more conservative. However, I have seen how the community work of many of our young leaders active in San Francisco’s Chinatown have strengthened their family relationships.

In giving back to the community through neighborhood clean ups, home visits to seniors, or campaigns for pedestrian safety, young leaders in Chinatown CDC’s Adopt-an-Alleyway Youth program, have a greater appreciation for the struggles which their parents and grandparents have gone through. At the same time, their parents are proud of their children embracing their Chinatown community as their own, even if the family has moved out to other San Francisco neighborhoods.

You were born in Chinese Hospital in Chinatown, and raised in Oakland, where your parents ran a restaurant. San Francisco’s Chinatown remained the cultural and social center in your life for your activism and for your work. Chinese American continue to settle all over the Bay Area, all over the country. Can you elaborate on the role of Chinatown now, and how it can serve and connect with the growing Chinese population?

San Francisco’s Chinatown will always have the honor of being America’s first Chinatown, “the place where it all started”, and it with a great deal of pride and responsibility that those of us who have devoted our lives to Chinatown can view our work. The Chinese American population in the Bay Area (and other major metropolitan areas) has long grown beyond the confines of our historic Chinatown. However, Chinatown is still the informal “Capitol” of the Chinese in the Bay Area, indeed of the Chinese in America, with all due respect to New York Chinatown, which is larger.

While San Francisco Chinatown may no longer must be the primary place for Chinese Americans to live, work and do business, it is still a cultural and political center for Chinese Americans. It has an important educational role in teaching Chinese Americans – young and old, immigrant and native born – our history in this country, a role which extends to educating other Bay Area residents and visitors from all over the world about the Chinese experience in America.

I was struck by how many of the fights over development that started in Chinatown led to changes throughout the city – and the nation. For example, environmental groups fought to pass a Sunlight Ordinance, to forbid projects that cast significant shadows on public parks.

Like NBC Asian America on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.

To outsiders, Chinatown seems insular. What are some contemporary issues that the neighborhood faces that you believe have citywide, state, and national significance?

San Francisco’s Chinatown has been an important inner city neighborhood where many innovative projects and strategies have been advanced and I am proud of the Chinatown CDC’s historic commitment to innovation in this “urban laboratory”, if you will. The City’s Sunlight Ordinance came out of a Chinatown land use battle. Chinatown and the Tenderloin together championed the first Residential Hotel Preservation Ordinance in the nation. Our many transportation innovations have included the first Park and Ride Shuttle program, diagonal sidewalk crossing “pedestrian scramble system” and our Chinatown Alleyways program has been a national model.

Today, Chinatown is experiencing similar challenges as many San Francisco neighborhoods with evictions and displacement, with a struggling small business environment, with pedestrian safety. I am not sure if there are simple “innovative” solutions to such issues, but I believe that Chinatown, historically and today, has shown that such complex issues require a keen sense of strategy, skilled coalition building both within our community and with other communities.

Short profiles are peppered throughout the chapters of the Chinatown activists and leaders. I was fascinated to learn how long many you have been working together in different roles and different organizations. Edwin Lee, Mayor of San Francisco, worked at the Asian Law Caucus. Sue Lee, executive director of the Chinese Historical Society, was a former program director at the Chinatown Community Development Center. Your frequent refrain is “What goes around comes around.” In what ways does a long-established relationship help or hamper, as in the case where groups may come out on different sides of an issue?

One of the reasons I wrote the book is to share how Chinatown has been able to survive the last half century and many complex issues which have seen conflict between different sectors or constituencies. Chinatown is in some ways a small town where everyone knows everybody else, and where the community grapevine is alive and well. I think that while at the times where serious internal conflict has occurred, there has been a sense that we can agree or disagree, but that ultimately we all care for the same community. This of course is not always evident in “the heat of battle”, but there is a sense of mutual respect within the community, respect across generations and political ideology which values relationships even when we at opposite sides of an issue. After all, we might need to work together on the next issue.

Interview was edited for clarity and length.