The writer, an adoptee, recently returned to South Korea to continue her search for her birth parents. This is her second essay about her experience. You can read her first essay here.

I'd been sleeping soundly until the pilot's voice broke my slumber, announcing our descent into Incheon International Airport. I quickly sat up, fastened my seat belt, and placed my pillow on my lap. After a total of 18 hours in flight from New York to South Korea, with a connection in San Francisco, all my joints cracked and popped as I stood up and pulled my carry-on suitcase from the overhead compartment, and the backpack from under my seat. I forced my feeble legs across the glossy, tiled, marble airport floors, grabbed my bags from the conveyor belt, and exchanged my U.S. dollars for South Korean won.

Smiling faces hovered outside the doors, holding welcome signs for family members and friends. I walked by them all. No one was here to greet me.

I glanced around as I walked through the airport. The "outsider" tag I wore growing up in a Caucasian household had already been removed when a middle-aged woman who befriended me on the flight said “You’re with your peeps,” as we landed. Here, instead of being the token Asian in public, I was surrounded by a sea of people with my round face, my black hair, my almond-shaped eyes, and my beige complexion.

Physical similarities only got me so far. I don't speak the language. So aside from the family friend who generously hosted me along with her network of family, friends and colleagues, I felt a constant cloud of shame hang over me. Taxi drivers and shop owners, assuming I was local, would start any interaction by speaking in Korean. My default response of ahn-nyong-ha-se-yo, (“hello, how are you”) was met with skepticism and a scowl, as they'd realize that was as far as the conversation could go.

This was the place my parents lived. This was the country from which I came. But I was a visitor here.

So I visited.

In Seoul, I indulged the American me by visiting all the must-see tourist stops: Gyeongbokgung Palace, Dongdaemun Market, N Seoul Tower and Bukhansan National Park. I learned about Korean Buddhism at an overnight program at Myogaksa Temple and meditation classes, visited my first bath house for a full body scrub, and got a new, modern trim with copper-red highlights at a high-end salon. I ventured outside of Seoul to witness breath-taking natural landmarks: Cheonjeyeon Waterfall, Seongsan Ilchulbong Peak, Hyeopjae Beach and Manjanggul Cave in Jeju Island, and visited a huge seafood market in South Korea’s second largest city, Busan.

Despite the language barrier I encountered along the way, the journey through my past liberated me from years of protective identity shells as I unraveled my birth history and Korean ancestry.

The social worker at my adoption agency in Seoul handed me a stack of thick folders.

My health history showed a minor case of jaundice, common among newborns. My birth mother's name -- Huh, Ok Ja -- appears on the initial social history form. I'm told Ok means jade in English. I think back to the jade necklace I'd packed with me for the trip, as protection, unaware of the maternal connection in my bag. There is no other information for her -- no date of birth, no contact number, and no address.

I learn that before I'd entered the adoption agency, I was at the birth clinic for one week following my birth. The medical workers kept me that long in case my birth parents changed their minds. My file contained photos of my foster mother, who raised me for three months before I was transported to New York, and my pre-flight report, my parents' application, and three post-adoption visit assessments.

"My baby, we and everyone loves you so. Someday, you will see that."

My foster mother had passed away, but the 73-year-old obstetrician who delivered me greeted me warmly on the clinic's first floor -- where I was born. Her son now runs a separate clinic on the first floor.

This deluge of faces, names, and paperwork from my past -- telling me the story of myself before the family I came to know as my own -- freed me from the resentment I'd held for so long. I forgave my birth parents. Their wish of a better life for me was granted.

I understand now that they did not think they could care for me. I want to thank them for making the right choice. But this visit to the country of my birth only makes me want to find them that much more.

Back home, in New York, I resubmitted a request with Korean Adoption Services to locate my birth family. Due to limited information, I'm told, the search just isn't possible. I'm left with only my mother's name, and a sheaf of papers telling the story of the weeks I spent between birth and adoption.

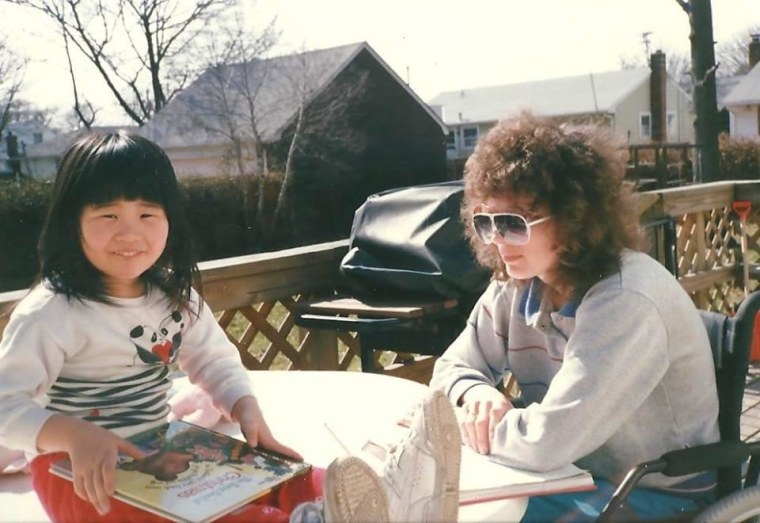

My adoptive mother - Julia - and I weren't connected by any genetic thread, but we were a perfect fit. Her journal - recently passed on to me by my father - only further confirms that.

Impeccable cursive entries from 1984 dissolve over time, as the multiple sclerosis set in, into less frequent and sloppy writings.

On March 20, 1987, she wrote, “My baby, we and everyone loves you so. Someday, you will see that. You don't know right now, but you help me physically and emotionally. You always say in your prayers "Jesus, Mommy Walk," and I will my dearest. Sometimes you just come out with that statement. It's as if you know something will happen. At 2.5, I believe your faith is as strong as mine. Sometimes on my lowest days, you are there to help me forget and remember the blessings I do have like you!”

There are other entries that resonate with me -- her reflections on parenting, musings on the events of her time like the Challenger Shuttle disaster and Hurricane Gloria. But each entry ends the same way - with a proclamation of her unconditional love for me.

I learned, through the journal, that it was important to my mother to show respect for my culture. In Korea, the first (dol) and 60th (hwangap) birthdays are the most important. In celebration of my first birthday, my mother dressed me in a traditional outfit and served fruit and rice cakes – food staples of the traditional dol. She didn’t want me to forget my native roots.

I don't want to forget them either. While visiting the UN Memorial Cemetery in Korea in Busan, I paid homage to the countries that allied with South Korea in the Korean War. The flags of the United States and South Korea stood side by side. I watched them flap in the wind, and I finally understood my place. I am of both countries, both cultures and both families. I am Korean-American.