A leader of the Kepler planet-hunting team has created a slow-moving scientific stir by telling an audience at a high-tech conference that our galaxy could harbor 100 million Earths, based on the space mission's raw data. The resulting buzz focuses not only on the findings, but also on the means by which they came to light.

The conclusions drawn by Harvard astronomer Dimitar Sasselov totally make sense, based on the composition of our own solar system. If we look at the eight dominant planets, four of them are Earth-scale, two are Neptune-scale, and the other two are big gas giants. (And then there are hundreds or thousands of smaller worlds like Pluto.)

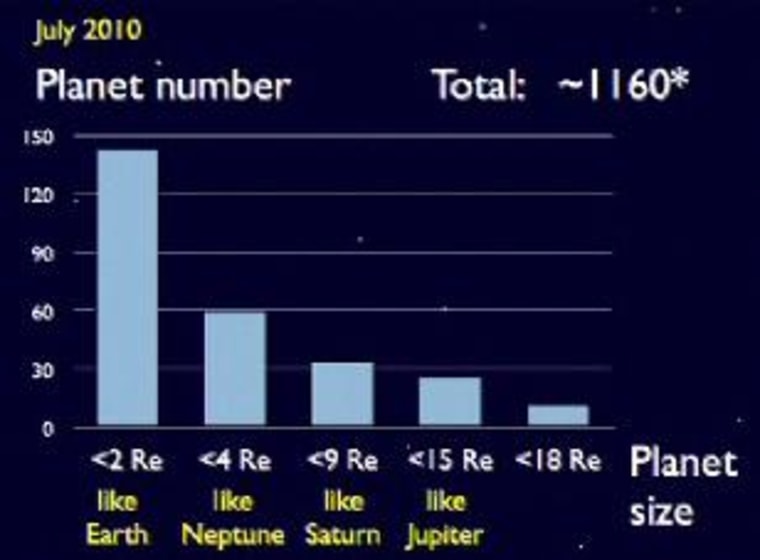

During his July 16 talk at the TEDGlobal conference at Oxford, Sasselov observed that the preliminary results from Kepler were following that pattern. So far, planetary candidates "like Earth" - those that are no more than twice as wide as our own planet - make up the largest category in Kepler's database, according to a chart Sasselov used to illustrate his talk. The proportion is significantly more than that for Neptune-sized, Saturn-sized or Jupiter-sized candidates. (These observations came just after the eight-minute mark in the video embedded above.)

"The statistical result is that planets like our own Earth are out there," Sasselov, a co-investigator for the $600 million Kepler mission, observed. "Our Milky Way galaxy is rich in this kind of planet."

If you extrapolate that kind of distribution to the entire Milky Way galaxy, there might be 100 million alien Earths out there, Sasselov said.

"That's great news," he told the TEDGlobal audience. "Why? Because with our own little telescope, just in the next two years, we'll be able to identify at least 60 of them."

Once those candidates are confirmed, follow-up observations would be conducted to study the planets' atmospheres and determine whether they could sustain life. The search for alien Earths, as opposed to alien Jupiters, naturally leads to the search for alien life, Sasselov explained. "Life as a chemical system really needs a smaller planet with water and with rocks and a lot of complex chemistry to originate, to emerge and survive," he said.

So when we're talking about millions of alien Earths, we're talking about one of the biggest stories in astrobiology.

The last word? Hardly

Sasselov emphasized that he was sharing preliminary findings, based merely on the candidates Kepler has turned up so far. The little Kepler telescope is built to gaze fixedly at a patch of sky for months, looking for the faint dips in the intensity of starlight that occur regularly when a planet crosses over the star's disk. Astronomers on the Kepler team say those detections have to be confirmed by other means. Why? It's because they want to rule out any possibility that the dips are being caused by some other mechanism, such as the mutual eclipses of binary stars.

The Kepler team has been holding onto much of its preliminary data for that purpose, with the big reveal scheduled in February. The fact that a lot of the Kepler data is still being held back has rubbed some scientists the wrong way - and the fact that Sasselov discussed an aspect of the findings that apparently had not yet been made public added to the controversy.

Once Sasselov's comments started making their way across the interwebs, NASA began facing questions over whether significant findings had slipped out of the Kepler team's net.

Some news outlets, such as the Daily Mail, fixed upon the suggestion in Sasselov's chart that 140 Earthlike candidates had been found, as well as his comment that Earthlike planets "with water and with rocks" were of particular interest. The buzz over Sasselov's remarks picked up last week when the TED website posted a video of his presentation.

New news, or new spin?

Responding to the buzz, NASA stressed that the Kepler team has confirmed detection of only five planets, not the 140 mentioned in the news reports. Sasselov, meanwhile, told Space.com that he was "simply repeating what was already announced" last month by the full science team.

"So no new news here - but more to come later in the year!" he told Space.com.

It's true that one of the research papers put out by the team goes into the size distribution question, but that paper goes only so far as to note that most of the candidates appear to be Neptune-sized or smaller. In fact, the earlier charts suggested that alien Neptunes are more numerous than alien Earths. So at the least, Sasselov's comments put a new, Earth-centric spin on the previously announced results.

ScienceInsider's Richard Kerr said Sasselov's presentation "was especially striking because it was largely based on Kepler data that team members had been allowed to keep to themselves for further analysis until next February. So, traditionally, such data would be released formally with all involved scientists onboard."

NASA Watch's Keith Cowing said he was confused by Sasselov's seemingly significant non-news: "The Kepler folks seem to want to have things both ways," he wrote. "On one hand they want to tantalize us (and select audiences) with what they have found but yet at the same time they do not want to put their reputations on the line when people start taking their comments as fact. This project clearly needs to put some PR strategy in place."

My efforts to get comments from Sasselov or other members of the Kepler team today were unsuccessful, but NASA spokesman Michael Mewhinney did tell me that the scientists are preparing a fresh response and would provide further clarification on Tuesday. So check back here for updates as they become available.

Update for 8:55 p.m. ET July 27: Sasselov tries to dispel the "confusion" over Earth-sized planetary candidates in a posting to NASA's Kepler mission blog. During his 18-minute TEDGlobal talk, "the expected number of planets, size and Earth-like chemistry got confused, and created a misunderstanding," he said.

In the blog posting, he emphasizes that the Kepler telescope can measure the size of objects as they pass over a star's disk, but can't say much about their climate or chemistry - let alone whether they have water or rocks. In fact, he notes that the Earth-scale planets detected by Kepler so far couldn't be Earthlike in the water-and-trees sense because they circle their parent stars in such hellishly close orbits. They're nowhere near the "habitable zone" within which life as we know it can exist.

"The first data release is an encouraging first step along the road to Kepler's ultimate goals, specifically, to determine the frequency of Earth-size planets in and near the habitable zone," Sasselov writes. "However, these are candidates, not systems that have been verified sufficiently to be considered as planets. The distribution of planet sizes may also change. It will take more years of hard work to get to our goal, but we can do it."

Sasselov is looking forward to reaching those ultimate goals because of another role he plays - as leader of Harvard's Origins of Life Initiative, which tries to make connections between planetary science and biology. In his TEDGlobal talk, he sought to emphasize that "progress in synthetic biology may be accelerated by input from planetary science." That's why he made the connection between Kepler and the search for life.

Another co-investigator for the Kepler mission, William Borucki of NASA's Ames Research Center, provided yet another follow-up in a telephone interview after Sasselov's blog posting was published. He said Sasselov's TEDGlobal lecture "was a little bit disturbing" because the discussion focused on "Earthlike" planets rather than "Earth-size" planets. "Earthlike is not Earth-size," Borucki said, for the reasons we've already mentioned.

Borucki also said the now-famous graph that Sasselov used was not quite correct, because the leftmost category actually takes in everything less than two and a half times as wide as Earth, not just twice as wide. The fraction couldn't fit on the original slide, but the graph would be corrected to bring it into sync with Figure 2 on page 7 of the scientific paper released by the Kepler team last month, Borucki said.

That figure shows that "super-Earths," between two and three times as wide as our own planet, make up the peak category for Kepler's candidates so far. Neptune-scale candidates (three to four times as big as Earth) make up the second-biggest category, and not-so-super-Earths (less than two times as wide as Earth) add up to the third-biggest category. There's a quick fall-off, however, when you're looking for things less than twice as wide as Earth. "By the time you hit one and a half [times as big as Earth], you've got nothing," Borucki said.

Borucki suspects that the fall-off is merely due to the fact that "we have not yet been able to bring these small transits out of the noise," and that Kepler will eventually find plenty of candidates trending down toward true Earth size.

So if you're looking for Earth's exact twin in the current crop of Kepler data, you'll be disappointed. But if you're looking for life, you needn't limit yourself to Earth size or smaller. In fact, Sasselov is among those who argue that super-Earths are superior for fostering life. And the Kepler database suggests that astrobiologists will eventually have a juicy selection of super-Earths to choose from.

Do Sasselov's amended remarks clear up the confusion that he referred to in today's blog posting? Or does all this talk about super-Earths, "Earthlike" vs. "Earth-size" and missing fractions make your head spin? Feel free to weigh in with a comment below.

Join the Cosmic Log corps by signing up as my Facebook friend or hooking up on Twitter. And if you really want to be friendly, ask me about "The Case for Pluto."