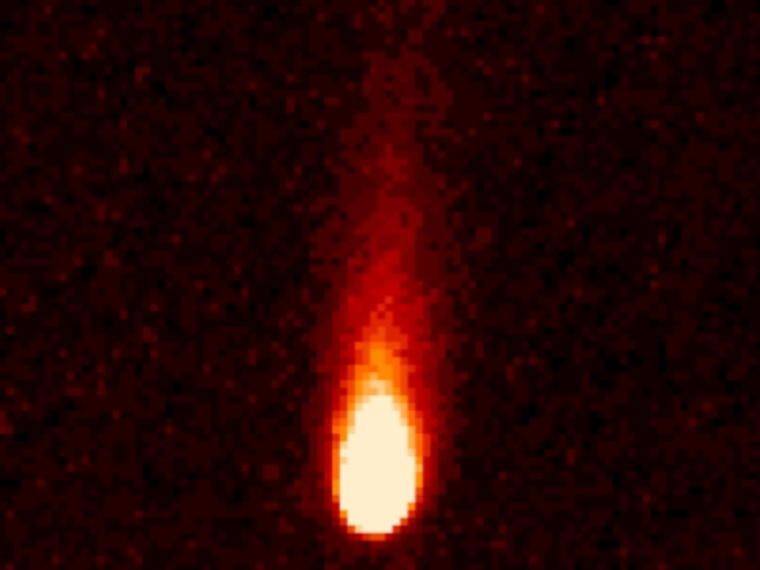

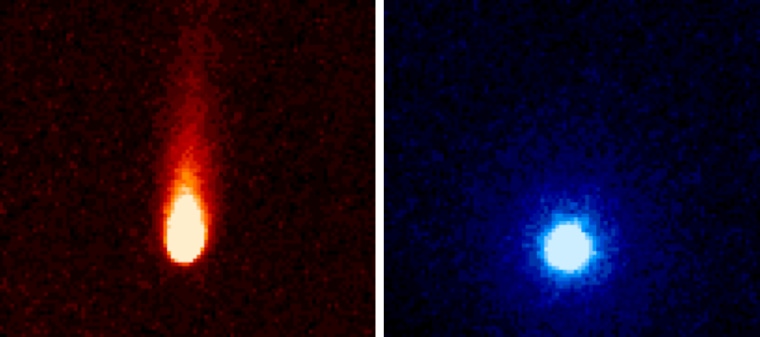

Newly released images from NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope show tons of what appears to be carbon dioxide spritzing away from Comet ISON, the dirty snowball that skywatchers hope will become the comet of the century.

Spitzer's infrared imagery indicates that 2.2 million pounds (1 million kilograms) of CO2 gas is fizzing away from the "soda-pop comet" every day, along with 120 million pounds (54.4 million kilograms) of dust, said Carey Lisse, a scientist from Johns Hopkins University's Applied Physics Laboratory who heads up NASA's Comet ISON Observation Campaign.

"Thanks to Spitzer, we now know for sure that the comet's distant activity has been powered by gas," Lisse said on Tuesday in a NASA news release.

Comet ISON is less than 3 miles (5 kilometers) wide, but the gas and dust emissions create a shining tail that stretches out for 186,400 miles (300,000 kilometers). It was discovered last September by Russian astronomers using the International Scientific Optical Network, when it was between the orbits of Saturn and Jupiter. NASA says that's a relatively early detection for a comet coming in fresh from the solar system's edge, and the strong CO2 emissions could be the reason why.

Spitzer's readings, which were made on June 13 when ISON was still a distant 312 million miles (502 million kilometers) from the sun, could shed light on the origins of the comet — and the origins of the solar system as well.

"This observation gives us a good picture of part of the composition of ISON, and, by extension, of the proto-planetary disk from which the planets were formed," Lisse said. "Much of the carbon in the comet appears to be locked up in carbon dioxide ice. We will know even more in late July and August, when the comet begins to warm up near the water-ice line outside of the orbit of Mars, and we can detect the most abundant frozen gas, which is water, as it boils away from the comet."

The comet isn't visible from Earth right now because of its location in the sky relative to the sun — but next month, skywatchers should get a better fix on how bright ISON is becoming.

In late November, the comet is projected to come within 700,000 miles (1.1 million kilometers) of the sun. If ISON survives that encounter, it could become one of the brightest comets in decades, if not the century. However, there's also a chance that the comet could fizzle out like Comet Kohoutek in 1973, or break apart like Comet Elenin in 2011.

More about comets:

- Comet ISON gets its day in the sun

- 'Comet of the Century' and other sky highlights

- NBC News archive on comets

Alan Boyle is NBCNews.com's science editor. Connect with the Cosmic Log community by "liking" the NBC News Science Facebook page, following @b0yle on Twitter and adding +Alan Boyle to your Google+ presence. To keep up with NBCNews.com's stories about science and space, sign up for the Tech & Science newsletter, delivered to your email in-box every weekday. You can also check out "The Case for Pluto," my book about the controversial dwarf planet and the search for new worlds.