Richard III may have been a blue-blooded royal, but to the roving parasites of the late Middle Ages he was just another piece of tasty human gut. New analysis of the king's remains indicate that Richard III had a clear case of intestinal parasites, brought on by hygiene that was at best medieval.

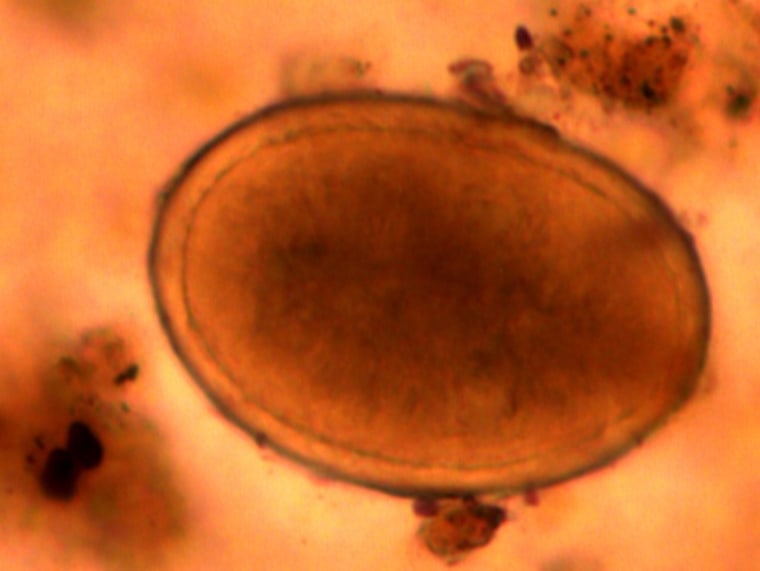

"This is the first time anyone has studied a king [or] noble in Britain to look for ancient intestinal parasites," Piers Mitchell, a paleoparasitologist and orthopedic surgeon at the University of Cambridge, wrote to NBC News in an email. In a sample taken from the king's remains Mitchell and a team of researchers have found the eggs of Ascaris lumbricoides, a simple roundworm.

"[T]hey may have been spread to Richard by cooks who did not wash their hands after using the toilet, or by the use of human feces from towns to fertilize fields nearby," Mitchell explained. Perhaps "salad vegetables became contaminated with eggs and were then eaten," he suggested.

In a brief report in the medical journal The Lancet, Mitchell and a team describe their analysis of the sample, and include an image of isolated roundworm egg seen under an optical microscope.

"Despite Richard's noble background, it appears that his lifestyle did not completely protect him from intestinal parasite infection, which would have been very common at the time," Jo Appleby, lecturer in human bioarcheology at the University of Leicester, who was part of the team that helped extract Richard's remains from a Leicester parking lot in 2012, said in a release.

Roundworm eggs were not found at other locations on the site, suggesting the worms were buried with the king. If Richard had sought treatment, it would have involved "bloodletting, modification of the diet, and medicines to get rid of the excess phlegm and so return humoral balance to normal," Mitchell explained.

Roundworm eggs make a poo-borne getaway from a host, and travel to a new one when fecal matter contaminates food. Today, poor sanitation is a major contributor to spreading infection. The parasite is "uncommon" in the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, but afflicts up to 1.2 billion people worldwide. According to the World Health Organization, roundworms claim 60,000 lives, mainly children, every year.

Gut bugs have been a global menace all through human history. Roundworms, tapeworms, hookworms and whipworms have been infecting humans for thousands of years. Among the oldest evidence, 10,000-year-old human coprolites (aka droppings) from caves in Utah contained traces of pinworm infection.

Ascaris lumbricoides, the kind of roundworm eggs found in Richard III, is well traveled, and the worm's progress is well documented due a tough chitin coating on the shell which allows the capsules to resist erosion by weather and time. Fecal evidence shows that it was infecting settlers in Peru in 2277 B.C. and Brazil in about 1600 B.C., and the worms were also found in an Egyptian mummy dating back to 1600 B.C.

In June this year, researchers showed that Richard the Lionheart's crusading armies were being cut down from within — waging and losing a war with gut parasites on their travels.

More about Richard III:

- Study suggests Richard III spoke with a lilt

- King Richard III's face revealed after 500 years

- Richard III's 'discovery' was reported in 1935, too

- Relatives add drama to the plans for King Richard III's final resting place

First evidence of Richard III's roundworms was presented in The Lancet as "The intestinal parasites of King Richard III" by Piers Mitchell, Hui-Yuan Yeh, Jo Appleby and Richard Buckley.

Nidhi Subbaraman writes about science and technology. You can find her on Facebook, Twitter and Google+.