Forty-five years after NASA's greatest success, the Apollo 11 moon landing, America's space agency is having a hard time getting its message across. It's gotten to the point that even moonwalker Buzz Aldrin is talking about how NASA seems to be "adrift" nowadays.

Houston, we have a marketing problem.

At least that's the argument that marketing strategists David Meerman Scott and Richard Jurek make in a newly published book with a fresh take on Project Apollo, titled "Marketing the Moon: The Selling of the Apollo Lunar Program."

Sign up for Science news delivered to your inbox

"The challenge today is one that a professional marketer would look at and say, 'The product life cycle has not been managed well,'" Jurek told NBC News. "In a marketing organization, a product manager's job is to look at the future, at that eventual decline, and ask, 'How do we extend that life cycle?' But that was not NASA's job. NASA became a victim of the political football that gets kicked around every four or eight years."

In their coffee-table book, Scott and Jurek don't focus so much on NASA's current hard times, but on the agency's genius for selling the space effort during the 1960s.

Back then, all the stars aligned, so to speak. There was a clear motivation for getting to the moon — to beat the Soviets, keep the moon from going red, achieve a peaceful Cold War victory.

There was ample money to execute the mission: Apollo cost $25.4 billion in 1969 dollars (which would be $135 billion today), and that didn't even include the cost of the preceding Mercury and Gemini projects. Those days are long gone: NASA's spending level has shrunk from 4.5 percent of the federal budget in 1966 to less than half a percent today, Jurek noted.

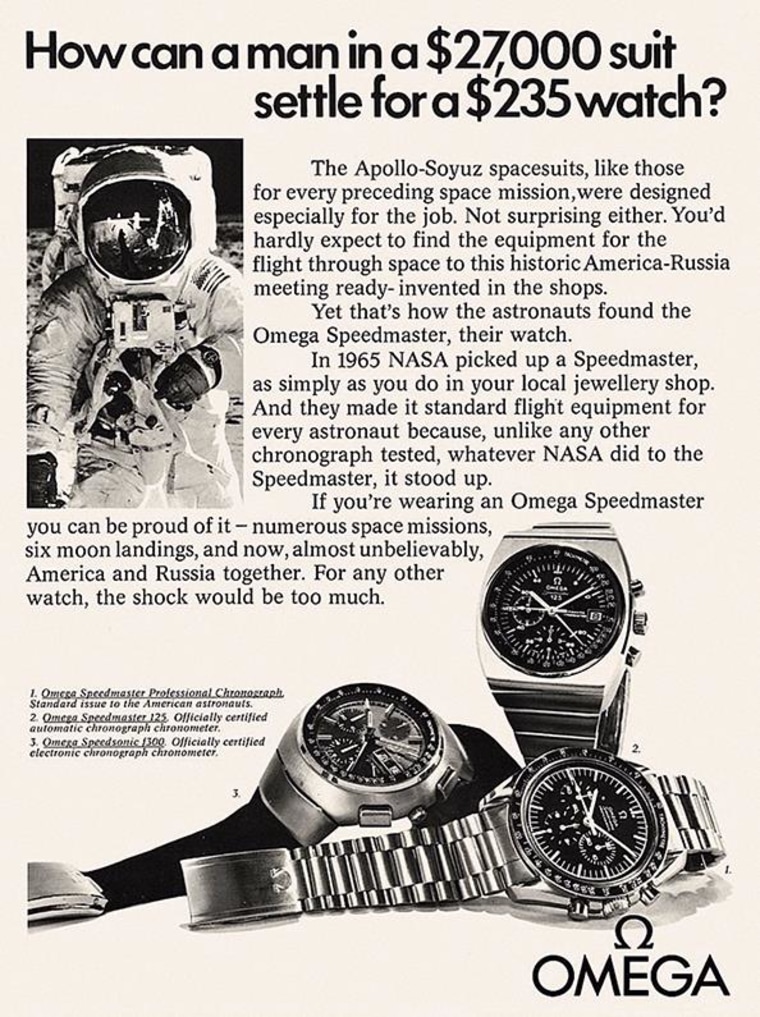

NASA also had a freer hand when it came to working with the private sector. Flipping through the pages of "Marketing the Moon" is like bingeing on "Mad Men" episodes. Advertising tie-ins to space were in abundance: Omega, for instance, touted its timepieces with a picture of a moonwalker and this headline: "How can a man in a $27,000 suit settle for a $235 watch?"

Space still figures in pop culture, but in ways that typically reflect astronaut sex appeal and science fiction rather than the facts of spaceflight. (The recent "Cosmos" TV series is a notable exception.) Even the best of the modern-day media opportunities don't lay out NASA's vision for the future the way Wernher von Braun did for Walt Disney in the 1950s.

Communicating NASA's vision may pose the greatest challenge. "If in 1966, at the peak of the space program, you asked any American what the purpose of the program was, they'd say it was to get humans to the moon and back again safely by the end of the decade," Jurek said.

It's harder for NASA to raise awareness about its current objectives for human spaceflight: conducting research on the International Space Station into the 2020s, sending astronauts to bring back a piece of a near-Earth asteroid by the mid-2020s, and then sending them to Mars and its moons in the 2030s.

In addition to those objectives for human spaceflight, NASA also has a robust robotic space exploration program, an environmental Earth-monitoring role, and a longstanding interest in aeronautical research.

"They're attempting to be all things to all people, beyond just human spaceflight," Jurek said. "Just as NASA was born out of a different governmental department in the 1950s — NACA, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics — maybe it's time to reformat NASA to refocus its mission."

In the book, Scott and Jurek say NASA is facing an "identity and brand crisis," and is yielding the spotlight to marketing-savvy entrepreneurs such as Virgin Galactic's Richard Branson and SpaceX's Elon Musk.

So how can NASA get its mojo back? Jurek says policymakers should consider splitting off NASA's human exploration program and robotic exploration program into separate agencies, and perhaps having other governmental offices pick up functions that don't fit the core mission.

Identifying that core mission, and then selling it to the public, is essential. NASA's stated objectives run the gamut from expanding human knowledge to defending Earth against asteroids — which means there's a lot to choose from.

"What NASA is missing is a global imperative."

"NASA's goals were aligned with the greatest problem of the day when it was decided to go to the moon," Jurek said. "We sit on the precipice of any number of global threats and dangers, and NASA would be better served by focusing its energies on those — for example, resource depletion and the future of humanity. What NASA is missing is a global imperative; a 'need to have' rather than a 'nice to have.'"

Could putting humans on Mars be part of a "need to have" imperative? Jurek said he was intrigued by Aldrin's vision to have robots build the infrastructure for human settlements on Mars, under the control of astronauts stationed on the Martian moon Phobos.

Creating that capability in telerobotics could lead to commercial space spin-offs such as lunar construction and asteroid mining, and the technology could also be applied to nuclear waste cleanup, deep-sea energy prospecting and other earthly needs.

"That could have huge benefits on Earth. You could get private ventures to fund that type of research," Jurek said. "If you look at that from a marketer's perspective, you'd say, 'That's kind of brilliant.'"